A Tool For Investors in Stock Market

How to give investors confidence, How to observe the chart patterns, chart reading, chart analysis

Course: [ Profitable Chart Patterns in Stock markets : Chapter 1. A TOOL FOR INVESTORS ]

"investors’ confidence” went up sharply in the Fifties. And obviously, the psychology of the market —that is, the sum of the attitudes of all potential buyers and sellers—is a crucial factor determining prices. It’s no use being "right” about a stock, if the market is "wrong.”

A TOOL FOR INVESTORS

What makes

one stock sell at $ 5 0 a share and another at $100?

And what

makes the market pay $ 5 0 a share for stock at one time—and $100 at another?

Well, there

are a company’s earnings, dividends, net worth, the outlook for its future

business, the outlook for the economy as a whole, the general behaviour of the

stock market . . . countless factors.

If a

diligent investor could learn them all, and balance them properly, he should be

able to predict the price of a stock—or so it would seem. Yet, assuming he had

a pretty accurate idea of how the earnings of International Business Machines

would rise over the last decade, how could he anticipate that I.B.M. would sell

as low as 12 times its annual profit in the late Nineteen Forties and at 60

times earnings in the late Fifties?

Obviously, "investors’ confidence” went up

sharply in the Fifties. And obviously, the psychology of the market —that is,

the sum of the attitudes of all potential buyers and sellers—is a crucial

factor determining prices. It’s no use being "right” about a stock,

if the market is "wrong.” How often does the market go down

following an announcement of good news, and up when the outlook seems dark! Put

another way, "a stock is worth only what

investors are willing to pay for it.”

Thus, to

predict the action of a stock, it would be ideal to have all the hard, economic

facts, plus an accurate insight into the minds of the public. That recalls the

sad old jest, "If I had some ham, I’d fix

me some ham and eggs, if I had some eggs.” The fact is, nobody can

know everything that may affect the price of a stock—not even the vaunted "insider.” To be sure, it’s an

enormous advantage to have advance knowledge about earnings, dividends, stock

splits, mergers, oil discoveries or new products. But to profit by such

knowledge, the insider—and his sisters and his cousins and his aunts—must buy

stock. In so doing, he increases the demand for the stock, just as when he is

ready to sell, he increases the supply. In either case, his action must

register itself in the marketplace, where the alert investor may observe the

signal.

Now while,

as we have just noted, nobody can learn all the factors that may determine the

price of a stock, in the last analysis all these factors meet in the market and

affect the interplay of supply and demand, which does set the price. No matter

what the news may be concerning a company, it will affect the price of its

stock only when it tips the scale in favor of either supply or demand. If, at a

given point, the demand for a stock (orders to buy) is greater than the supply

(orders to sell), the price must go up. If supply exceeds demand, the price

must go down.

Charts

provide a record of this interplay of supply and demand—a history at-a-glance

of the trading in a stock, or group of stocks, showing how many shares were

traded, at what price and when.

The purpose

of "chart reading” or "chart analysis” is to determine the

probable strength of demand versus pressure of supply at various price levels,

and thus to predict the probable direction in which a stock will move, and where

it will probably stop.

The clues

are provided by the history of a stock’s price movements, as recorded on a

chart. In the market, history does repeat itself—often. On the charts, price

fluctuations tend, with remarkable consistency, to fall into a number of

patterns, each of which signifies a relationship between buying and selling

pressures. Some patterns, or "formations,”

indicate that demand is greater than supply, others suggest that supply

is greater than demand, and still others imply that they are likely to remain

in balance for some time.

Before going

any further, let us be clear and emphatic about this: there is no infallible

system for predicting stock prices. If there were, the inventor of the system

would eventually own all the stock in the market. Rather than being infallible,

charts are often misleading or misunderstood—so much so, that we try to point

this out throughout this book and we also have included a chapter on the

pitfalls of chart reading at the end of this book.

Fortunately,

it’s not necessary to be right all of the time to make money in the stock

market. It’s only necessary to be right more often than you are wrong. This principle

is well known to gamblers, who say "the

house never loses.” Actually, the house often loses—at least often

enough to keep the customers coming back—but that mathematical edge assures

that the house will win in the long run. How can one find such an edge in the

stock market? Certainly, sound, thorough information about a company, its

industry and the economy are valuable. But a knowledge of the stock’s chart

action, and a familiarity with chart patterns, will help the investor decide

when to buy and when to sell.

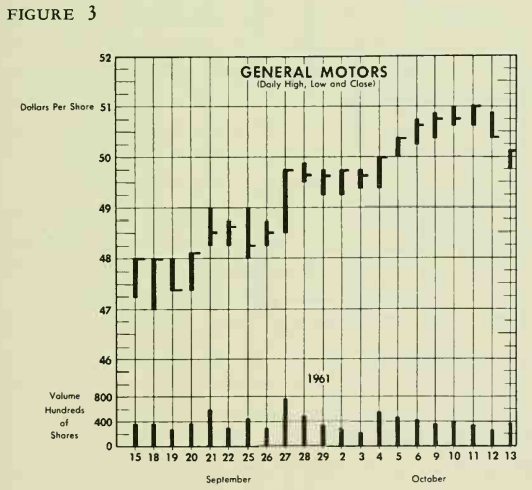

Now, a look

at how the chart is made. (Experienced chart readers may skip the rest of this

chapter, but we’d be delighted to have them stay along.) The charts used in

this book—and most widely used in price forecasting—are called Vertical Line

Charts, the kind that newspapers use to depict the stock averages. There are

many other kinds and variations—composed of lines, bars, steps or other

symbols, plotted on logarithmic, square root or arithmetic scale. Some analysts

use oscillators, moving averages, ratios or "points

and figures.” Each of these has its merits and its function, but all

take a lot of time to keep up, and their interpretation is generally highly

complicated.

By contrast,

the Vertical Line Chart may easily be kept and understood by anybody, in a

minimum of time. It presents at a glance the most pertinent information—the

highest, lowest and closing prices and the number of shares traded in a given

period. It is also the most time-tested method, having grown in use since the

turn of the century. Vertical Line Charts showing the course of leading stocks

and market averages for many years are available to the investor through

various chart publications. They provide ready-made, up-to-date charts of

leading stocks, and he can easily build and maintain his own charts for the

stocks he is interested in.

The chart is

built to show either daily, weekly, monthly or even yearly price fluctuations.

The same patterns can be recognized in any of these, and they may be used with

equal effect in forecasting—but the daily chart will often signal a turn more

quickly, and so most of the illustrations in this book are daily charts. Weekly

and monthly ones are handy, however, for studying long-range trends, and

examples appear at the end of the chapters that follow.

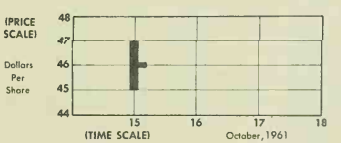

In any case,

the price information is entered on graph paper of the ordinary kind, with even

horizontal and vertical rules. The up-and-down scale, printed on the sides,

measures prices; the scale along the top or bottom indicates the time it

happened—the day, week, month or year, as the case may be. From the stock

market table, as published in the newspapers, or reported on the ticker, the

chart-maker enters a dot to mark the highest price at which the stock was

traded that day, and another dot to mark the low. A vertical line drawn between

these dots shows the price range for the day. A short, thin crossline will mark

the price of the last transaction of the day. For example, a stock that was

traded Oct. 15 at prices ranging from $45 to $47 a share, with the last trade

at $46, will appear as follows:

Weekly,

monthly or yearly charts are, of course, drawn in the same way, with each line

corresponding to the price action for such a period.

Space is

provided at the bottom of the chart to add an important piece of information:

the number of shares (or volume) traded during each period. This is recorded as

a vertical bar extending up from zero to the correct figure, in accordance with

a scale along the side. (In news-paper market tables, the volume is given in

hundreds of shares, or "round lots,” unless otherwise indicated.)

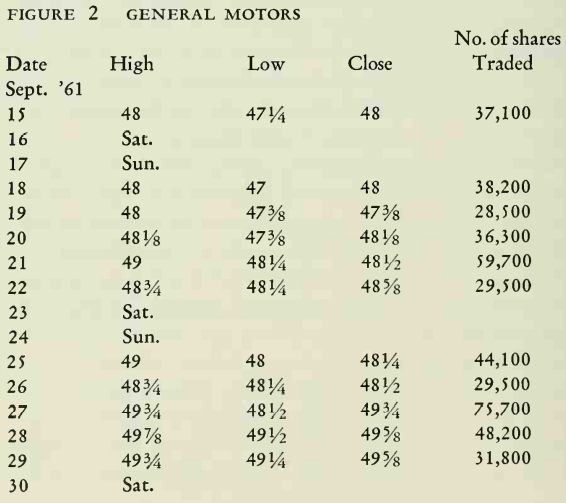

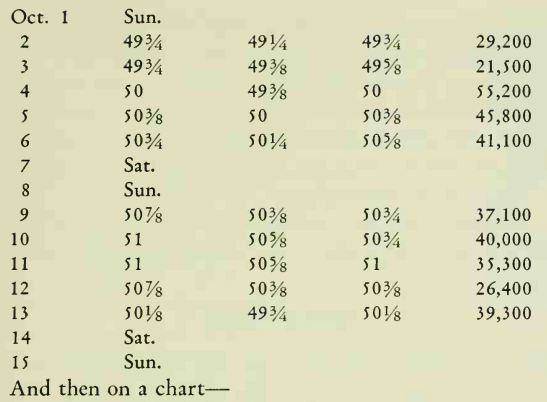

The

convenience—indeed the necessity—of charts may now be seen by considering the

daily market action of General Motors stock from Sept. 1 5 to Oct. 15, 1961,

first on a table of figures—

The first

vertical line shows that, on Sept. 15, prices paid for G.M. ranged from a high

of 48 to a low of 47.1/4, closing at 48 (horizontal dash);

the line at the bottom shows that 37,100 shares of G.M. were traded that day.

The same

procedure was followed for each day through Oct. 15. (It will be noted that

space for week-ends is eliminated to provide continuity.)

These data

may be condensed, for the purpose of examining long-term trends, into a weekly

range chart, as follows:

Profitable Chart Patterns in Stock markets : Chapter 1. A TOOL FOR INVESTORS : Tag: Candlestick Pattern Trading, Stock Markets : How to give investors confidence, How to observe the chart patterns, chart reading, chart analysis - A Tool For Investors in Stock Market