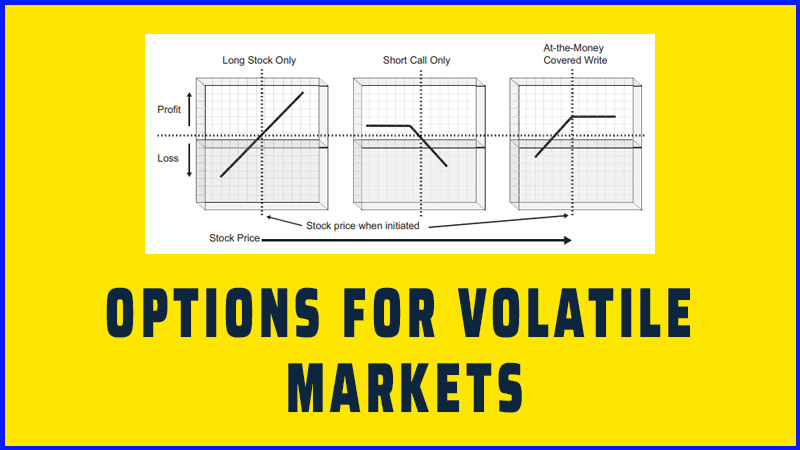

Basics of Option from Volatile Markets

Basics of option, what are options, List of options from volatile, define assignment and exercise, Define positions in Volatile

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 1: Option Basics ]

Options |

To understand and implement option strategies effectively, you need to understand not only how stocks and the equity markets work, but what options are, how they function, and what affects their value.

OPTION BASICS

To understand and implement option

strategies effectively, you need to understand not only how stocks and the

equity markets work, but what options are, how they function, and what affects

their value. The strategy discussions in this book assume you are already

familiar with stocks and options, so to refresh you on the basics, we have

constructed Chapters 1 and 2 as a review of listed equity options. If you are

already familiar with options, you can begin reading about call writing in

Chapter 3.

What Are Options?

An

option is a contract representing the right, for a specified term, to buy or

sell a specified security at a specified price. Like stock, they are also

standardized so they can trade on formal securities exchanges and are regulated

by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

There are two types of options: puts

and calls.

- Call option: A contract representing the right for a specified term to

buy a specified security at a specified price.

- Put option: A contract representing the right for a specified time to

sell a specified security at a specified price.

The specified price is known as the

strike, or exercise, price; the specified term is determined by the option’s

expiration date; and the specified security is referred to as the underlying

security. There are exchange-listed options on a number of securities and even

non-securities (such as indexes), but this book is devoted entirely to those on

stocks and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).We may refer to both of these in

aggregate as equity options. A standard equity option represents 100 shares of

the underlying stock or ETF Thus a call option on Disney with a strike price of

$35 that expires in two months gives the buyer the right, anytime during the

next two months, to buy 100 shares of Disney at $35 each.

- Strike price: The price at which the underlying security of an option can

be purchased or sold by the contract buyer.

- Expiration: The date when the terms of an option contract terminate.

- Underlying security: The security that an option gives its buyer the right to

buy or sell.

An option contract is not issued until

a buyer and seller come together in the marketplace. When an exchange initiates

trading on a particular option, no contract exists until the first transaction

takes place. The option is issued when party A agrees to buy one or more

contracts from party B, and additional contracts are issued as other buyers and

sellers make deals.

Standardization

Although options contracts are legally

binding, you need not call your attorney to draw one up when you want either to

buy or to sell. Option contracts are originated and standardized by an

independent entity called the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC). To comply

with SEC regulations, the OCC files a prospectus for all options on behalf of

all the buyers and sellers. It also sets, guarantees, and enforces all contract

terms and keeps the master versions of all contracts. You see only a trade

confirmation, as you most often do with stocks. (If you are curious, you can

see the OCC prospectus on the Internet at www.optionsclearing.com under

Publications.)

OCC:

The Options Clearing Corp., an independent entity that acts as the issuer and

guarantor for all listed option contracts.

By standardizing contracts, the OCC

enables options to be traded in the secondary market (on an exchange), just

like a listed stock or bond. In other words, they are interchangeable, or

fungible. When you buy 100 shares of Disney common stock for your account, you

know that those shares are exactly the same as any other Disney common shares.

Similarly, the OCC guarantees that when you buy a particular Disney call

option, your contract has the same terms—that is, it is for the same type of

option, on the same underlying stock, with the same strike price and

expiration—as all others referred to with the same designation. All options

having identical terms are said to be part of the same series and are

interchangeable.

- Class:

All the options of the same type that have the same underlying security. For

example, all the call options that exist for Microsoft stock are part of the

same option class.

- Series:

All the options in the same class that also have the same strike price and

expiration date. For example, all IBM calls in January with a strike price of

150 are part of the same option series.

Listed options are those that are

formally traded on a recognized exchange. Non-listed, or over-the-counter

(OTC), options also exist, but they are not standardized and are used

infrequently. For the most part OTC options are only used by institutions. All

the options reported through quote services are listed, and options may be

listed on more than one exchange. This does not affect the option’s

interchangeability. Option exchanges generally trade during the same hours as

the underlying stocks plus a few extra minutes at the end of the day (4:02 P.M.

Eastern time), except on the Friday before expiration, when they stop trading

right at 4 P.M.

The OCC plays another important role: as intermediary between option buyers

and sellers. When you buy or sell an option, you are actually dealing directly

with the OCC (through your broker), rather than with a particular individual.

That means you do not need to worry about the integrity of the transaction or

about the other party’s ability to pay. Their broker worries about that.

Option Listings

The option exchanges determine what

options they will list—in other words, which underlying stocks they will allow

options to trade on. Thus IBM, for instance, has no say as to whether options

are listed on its shares. Currently, options are available on approximately

2,600 stocks and ETFs, with new listings added every month. The reason that

figure is so small compared with the total universe of listed stocks is that

only certain stocks meet the exchanges’ requirements. Because of the close

relationship between options and their underlying securities, primary among the

exchanges’ criteria are that the underlying stocks be listed and actively

traded on a national market. Other requirements concern the number of shares

outstanding, the stock’s price history, its daily trading volume, the company’s

assets, and so on. As an example, new options listings are not approved for

stocks trading below $7.50.

TABLE 1.1 Option Examples

|

Underlying Security |

Expiration Month |

Strike Price |

Type |

|

Disney |

October |

35 |

Put |

|

Home Depot |

August |

35 |

Call |

|

IBM January |

January |

150 |

Call |

|

Intel |

April |

17.50 |

Call |

|

Microsoft |

July |

26 |

Put |

Since 100 shares is the standard

contract size for a single option, you only need to identify any option by the

four items that make it unique: underlying stock; expiration month; strike

price; and type. Table 1.1, for example, shows that IBM Jan 150 call designates

a call option on IBM shares, expiring in January, with a strike price of 150.

Strike Price

Options on a particular stock are

always available for at least several different strike prices above and below

the current price of the stock. The number of strikes, which can sometimes rise

to 50 or more on a single underlying, depend on the stock’s price and

volatility (how much the share price has moved historically). A volatile stock

such as Research in Motion (RIMM), for example, currently has more than 50

strike prices for the January 2011 expiration month. The option exchanges offer

strikes in increments of $2.50, $5, or $10, depending on the price of the

underlying stock. Thus, if XYZ is selling for around $50 a share when options

trading on the stock begins, the exchange would typically allow trading (for

both puts and calls) on a range of strike prices including, say, $40, $45, $50,

$55, and $60. On the other hand, if the share price is $16, you would probably

see strike prices of $15, $17.50, and $20. As stocks move, new strike prices

are added, although the exchanges generally do not add new strikes during the

last few weeks before an expiration.

Depending on the price of the

underlying stock at the time, options at various strike prices are said to be

in the money or out of the money. These terms are important to the covered

writer (option seller) and will be referred to frequently in the text.

- In the money (ITM): Describes a call option whose strike price is below the

current price of the underlying stock or a put with a strike above the current

price. Example: When ABC stock is trading at $43, call options with strike

prices of $40, $35, and $30 are all in the money.

- Out of the money (OTM): Describes a call option whose strike price is above the current

price of the underlying stock or a put with a strike below the current price.

Example: When ABC stock is trading at $43, call options with strike prices of

$45, $50, and $55 are all out of the money.

- At the money (ATM): Describes an option that has a strike price equal to (or

close to) the current price of the underlying stock. Example: A GHI call option

with a strike of $30 is at the money when the stock is trading at or very close

to $30.

Expiration

The most distinctive characteristic of

options is their limited life, determined by the expiration date. On that date,

they cease to exist, and any value they may have contained up to that point

becomes moot. In contrast, when bonds mature, they can no longer be traded but

they do make their last interest payment and repay their principal. When

options expire, if they are in the money (ITM) by any amount (even $.01), they

are automatically exercised by the Option Clearing Corp. It is important to

remember whether you are a buyer or a seller of options.

To keep things standardized, all the

options expiring in a particular month do so on the same day: the Saturday

following that month’s third Friday. Saturday was chosen to give brokers one

last morning following the last trading day to reconcile their clients’

positions and make sure there are no errors going into expiration. The third

Friday of each month is therefore the last day expiring options can be traded.

Expiring options can be bought or sold as usual on this Friday, but trading is

frequently heavier than average, as people close out positions before they

expire.

There are now options on some stocks

and ETFs that expire at the end of each quarter or even each week.

One glance at an option table in the

Wall Street Journal or on a computer shows that options on different stocks

have expirations in different months. It may appear strange to have options on

one stock expire in January, February, April, and July while options on the

next one expire in January, February, May, and August. Actually, there is logic

to this, although it may seem a bit obscure. When options first began trading

on formal exchanges in the 1970s, expirations were quarterly. Thus, for every

stock, only three-month, six-month, and nine-month options were initially made

available. Then, when three months passed and the first option expired, a new

nine-month option would be added on to the end. It was done that way because

there was not enough volume (liquidity) in the beginning to justify having

options expiring every month for individual stocks, and because the quarterly

cycle enabled the exchanges to offer option expirations that corresponded to

the quarterly earnings calendar of the underlying companies.

So, in the beginning, options were

designated to expire in one of the following three quarterly cycles (just to

spread them out evenly throughout the year):

- January-April-July-October.

- February-May-August-November.

- March-June-September-December.

Only three of the cycle months would be

available at any one time, and when the nearest expiration passed, the next one

in the calendar cycle would be added. If ABC options were introduced in cycle

#1, they might begin trading with expirations in January, April, and July. On

the Monday after the January options expired, the exchange would allow trading

in October options, so that there would once again be three expiration months

available.

For stocks on the January cycle, the

process worked as follows:

|

When |

Expirations Available |

|

As of January 1: |

January-April-July |

|

When January options expired: |

April-July-October |

|

When April options expired: |

July-October-January |

. . . and so on.

It became evident, however, that both

option buyers and sellers were more interested in the near-month expirations

(the current calendar month and the next one out) than in the expirations three

to nine months away. Reacting to this, the exchanges permitted the addition of

two near-month expirations while keeping intact the quarterly cycle structure

for the months farther out. So, today, instead of only three available

expiration months at any one time, there are four—the two nearest months and

the next two months in the quarterly cycle.

The January cycle now works as follows:

|

When |

Expirations Available |

|

As of January 1: |

January-February-April-July |

|

(February is now added so that there

will be two near-month expirations.) |

|

|

When January options expire: |

February-March-April-July |

|

(March is added as the second near

month.) |

|

|

When February options expire: |

March-April-July-October |

|

(There are already two near months,

so October is added as the next quarterly month.) |

|

. . . and so on.

Don’t feel that you need to memorize

these rules. Just be aware that there will always be two near-month options

available for each stock and two expiration months farther out that will vary

from stock to stock.

Since their inception in 1990, options

with greater than nine-month terms have also been available. They are called

long-term equity anticipation securities (LEAPS) and are available on close to

800 stocks at the present time. LEAPS usually expire in either December or

January and may be available as far out as three years. Otherwise, they work

the same way as regular listed options. As time brings them into the normal

option expiration cycle, LEAPS become the regular option for that month,

whether December or January.

Adjustments

When certain events affecting an

underlying security occur—such as a stock split, merger, or spin-off—the terms

of the option contract need to be adjusted so that both holders and writers

have essentially the same position after the event as they did before it. These

adjustments may affect strike price and number of underlying shares, but never

expiration date.

Say XYZ Corp. decides to split its

stock two-for-one. The company is issuing an additional share for each one

currently outstanding, and the share price is consequently cut in half.

Stockholders thus retain the same percentage ownership in XYZ Corp. after the

split as before. But the holder of an unadjusted call option on XYZ would have

the right to buy 100 shares that represent only half as much ownership in the

company as before. The terms of option need to change to reflect the change in

the underlying stock.

TABLE 1.2 Effect of Stock Splits on Options

|

|

Before Stock Split |

After Stock Split |

|

Price of XYZ stock |

$85/share |

$42.50/share |

|

Stockholder |

Owns 200

shares |

Owns 400

shares |

|

Option Writer |

Short 2

Jan 85 calls |

Short 4

Jan 42.5 calls |

Adjustments are decided upon, and

effected by, a joint panel of the option exchanges and the OCC. In the XYZ

example, on the effective date of the split, both holders and writers of

existing options on the stock would have the number of their contracts doubled

and the strike prices of these contracts halved. The before-and-after scenario

is illustrated in Table 1.2.

Odd splits, such as 3-for-2 or 5-for-4,

can yield even stranger fractional strike prices, such as 16.7. There cannot,

however be a fractional option, so in these odd splits, the number of shares

represented by one contract may change—to 133 or 150, for example—to match the

new strike price.

Regular cash dividends (those equal to

less than 10 percent of the value of the stock) are not considered sufficient

to adjust the terms of an option. The rationale is that these dividends are

built into the price of the stock over time and do not materially change the

value enough to warrant specific option adjustments. Besides, it would be

impractical to do so every time a company issued a regular dividend.

When a company spins off a new entity,

shares in the spin-off become part of the deliverable in outstanding option

contracts. If company XYZ, for example, issues 10 shares of QRS for each 100

shares of XYZ common, a contract formerly calling for the delivery of 100

shares of XYZ will now call for 100 shares of XYZ and 10 shares of QRS.

Exercise and Assignment

While it is certainly possible, and in

fact commonplace, to buy and sell options without ever exercising them, it is

very important for all option investors to be aware of the process and

implications of exercise and assignment.

The Basic Mechanics

When holders wish to invoke the right

given them by their option to buy or sell the underlying stock, they are said

to exercise their option. This is accomplished by informing their broker.

Notice can be verbal, just like placing an order to buy or sell stock (which is

essentially what an exercise is anyway). Thus, if you hold a call option for

DEF stock and you decide to exercise, you are essentially entering a buy order

for DEF at the strike price, except that your order would be routed to the OCC

rather than directly to the exchange where the stock trades. Exercises take

effect at night after the close of trading. Since the price is determined by

the option strike, it does not matter what time of day an option is exercised.

Options that can be exercised at any

time before expiration are said to be American style; those that can be

exercised only at expiration are called European style or capped. This has

nothing to do with where they trade. Equity options on individual stocks all

trade American style. Index options trade European style.

As noted above, the standard contract

size (or unit of trading) is 100 shares. That is the number of shares that the

writer must deliver if a holder exercises the contract. These shares are

sometimes referred to as the deliverable. There are listed options on common

stocks as well as on some preferred stocks and American depositary receipts

(ADRs) on foreign securities and on various other financial instruments,

including futures and stock indexes. Index options may stipulate cash delivery

instead of physical delivery, because of the practical considerations of buying

every stock in an index. All equity options require physical delivery of the

underlying shares. The process of actually delivering an underlying security as

part of an option exercise is called settlement and is handled by your broker

just like the settlement of a regular stock transaction.

When an option is exercised by one or

more holders, the OCC must determine to whom in the writers’ pool to assign

that exercise for fulfillment—in other words, which writer has to sell his or

her stock. The notification process is referred to as an assignment. The OCC

keeps the master record of which member brokerage firms are either short or

long every option. It distributes assignments by passing them to member firms

that have open short positions and letting them figure out which of their

customer accounts receive assignments. The brokerage firms must have fair and

reasonable ways to distribute assignments, but they do not all have to be the

same. Some firms distribute assignments randomly, while others use a

first-in/first-out policy.

Receiving an assignment notice from

your broker is essentially the same as receiving a trade confirmation for

buying or selling shares of stock, except that you did not have to enter an

order—it was generated by the assignment notice. This should occur early in the

morning following the exercise, but there is no guarantee on the exact time.

The broker receives word during the night from the OCC and will want to let you

know as soon as possible the next morning so that you do not unknowingly close

your call position or sell your stock in the market that day. (Writers are not

allowed to close a position once they have been assigned, even if the broker

has not yet informed them of the assignment.) As soon as any of your short

options are assigned, that, of course, eliminates those positions.

Say a holder of five Altria Group (MO)

June 25 calls decides to exercise them. The OCC informs Charles Schwab that it

is being handed an assignment for the calls. You are among the clients at

Schwab who are short the MO June 25 calls. As it happens, you have 1,000 shares

of the stock and are short 10 calls. Schwab informs you that “you have been

assigned on 5 MO Jun 25 calls,” and you subsequently receive a trade

confirmation that you sold 500 shares of MO at $25. You are left with 500

shares and five short calls—plus $12,500, less commission, added to your

account.

- Exercise: The action that option holders take when they notify their

brokers of their intent to invoke the right to buy (or sell) stock as

stipulated in their option. When call holders exercise, they are purchasing the

underlying stock at the designated strike price.

- Settlement: The process of delivering an underlying security (or other

stipulated interest) as a result of an option exercise. Stock options always

stipulate physical delivery of the underlying shares.

- Assignment: The action that the OCC and your broker take in selecting

option sellers (writers) to fulfill the obligation stipulated by the option

they sold. When call writers receive assignment notices from their brokers,

they are selling the underlying stock at the designated strike price.

Since the OCC is the intermediary for

all option transactions and assignments, it is able to keep track of how many

contracts are outstanding at all times and determines at the end of each day

how many are open (remain unclosed). The OCC publishes this number each day as

the open interest.

- Open interest: The number of existing contracts that remain unclosed for a

particular option. This figure is usually published each trading day by the OCC

and is net of all trades that have occurred up to the close of the previous

day. In conjunction with the daily volume of contracts traded, it provides an

indication of the option’s liquidity (how easily it can be traded).

Expiration is the grand finale of the

option opera. Once trading stops at the end of the Friday before an expiration

Saturday, the only other actions that can take place are exercise and

assignment. By Monday morning, that option is history. You won’t even see it

among your account holdings anymore, although you will generally see the expiration

on your activity screen. If you are short a particular option, however, you

will receive notification from your broker confirming whether it expired or was

assigned.

By the time expiring options stop

trading on Friday afternoon, the ones that are in the money will generally be

in the hands of market makers and other professionals, who will exercise them.

Most speculators will have traded out and closed their positions. Regardless of

who owns the options, however, you can expect them to be exercised. If they are

in the money by more than $0.01, they will be exercised automatically (by OCC

rules).

By the way, you do pay commissions on

exercises and assignments, since they are essentially the equivalent of buy and

sell orders.

Positions

The buyers of an option are considered

holders. This is a virtual term only; there is nothing physical to hold. In

fact, there are no certificates with options—everything is done by book entry.

But since the buyers pay money, they are considered owners of the options. As with

stock, when you buy an option, you create a long position in your account.

The option seller is also called the

writer. Again, this is just a label, a holdover from the old days, when put and

call contracts were actually written by people who owned stock and offered

these options for sale. Writers receive money, and their position is considered

short. The terms buying and selling are actions. The terms long and short

describe positions, indicating whether you actually have possession of the

asset or not.

As with stocks, you can initiate an

option position by buying (going long) or selling (selling short) as your

opening transaction. With covered writing, your opening transaction is to sell

one or more call options short. Once you have become either a holder or a

writer of an option, you can close your position anytime before expiration, as

long as the option is trading, simply by executing an offsetting, or closing,

transaction at the prevailing market price. The only catch is that you must

accept the market price for the option in effect at the time. To close a short

position in a call option on XYZ stock, for example, you would simply buy a

call on XYZ with the same strike and expiration. When you close your option

position, you wipe the slate clean, completely eliminating any further rights

or obligations from prior contracts.

Since you can initiate an option

position by either buying or selling, four scenarios are possible when you

enter any option order. You may:

- Buy to open (if you are simply buying a put or call).

- Buy to close (if you are already short an option and are closing out).

- Sell to open (if you are initiating a covered write).

- Sell to close (if you had previously bought an option and are now closing).

It is standard practice throughout the

industry to require you to indicate on every option order whether you are

opening or closing. (You will also usually be asked whether an opening sale is

covered or naked; for a discussion of these terms, see the next section.) This

information does not affect your trade or the price in any way.

- Holders:

Those who initiate a position by buying an option. They do not actually hold

anything physical. What they hold is the right to buy or sell stock.

- Writers:

Those who initiate a position by selling an option. Writers are obligated to

fulfill the buyers’ right to buy or sell stock. They do not actually write

anything, though in the very early days of option contracts, it would generally

have been the seller who would have written a contract and offered it for sale.

- Long:

Term used to describe the position of an option holder.

- Short:

Term used to describe the position of an option writer.

Covered versus Naked

When you write a call option, you are

contractually obligated to deliver (sell) the underlying stock if assigned. If

you own enough of the underlying stock to make good on this obligation, then

your option is considered covered. It’s like saying it is secured in the

banking world. Since you own the underlying stock, writing a covered call

option entails no additional risk: You can deliver the stock upon being

assigned, regardless of the share price at the time. If, on the other hand, the

stock is not in your account when you write the call, your option position is

considered uncovered, or naked. An uncovered call option exposes you to a

theoretically unlimited loss if the stock goes way up, because you will have to

buy it to fulfill your obligation to the OCC and the option holder when the

contract is exercised.

TABLE 1.3 Covered versus Naked Examples

|

Stock

Position |

Option

Position |

Status |

|

Long 500

ABC |

Short 5

ABC calls |

Fully

covered |

|

Long 600

DEF |

Short 4

DEF calls |

Fully

covered |

|

Long 800

GHI |

Short 10

GHI calls |

8 calls

covered; 2 calls

naked |

|

Long 0 JKL |

Short 4

JKL calls |

4 calls

naked |

The fact that one option contract

represents 100 shares of stock means that you must remember this multiplier

(100) when figuring how many contracts to buy or sell. To sell (write) options

on more than 100 shares, you would simply sell multiple option contracts. For

300 shares, you could sell up to three contracts. For 1,000 shares, you could

sell up to 10 contracts, and so on. There are no fractional option contracts,

and thus no way to buy or sell a listed option for fewer than 100 shares.

(Occasionally, however, some options that have been adjusted for splits may be

for 150 shares, and that will be made known to you.) So if you happen to have

an odd number of shares, such as 458, you will only be able to write covered

calls against 400 shares.

You can certainly have more than the required amount of shares in your account than you need to deliver if your calls are assigned. Say you own 1,000 shares of DEF and sell six DEF calls. You would at most have to deliver 600 shares if assigned, so you’re completely covered. But if you have 1,000 shares and sell 12 calls, then two of those calls are naked. See Table 1.3 for examples.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 1: Option Basics : Tag: Options : Basics of option, what are options, List of options from volatile, define assignment and exercise, Define positions in Volatile - Basics of Option from Volatile Markets

Options |