Options Trading: Put Hedging basics

Put Hedging basics, Advantages of put hedge, Disadvantages of put hedge

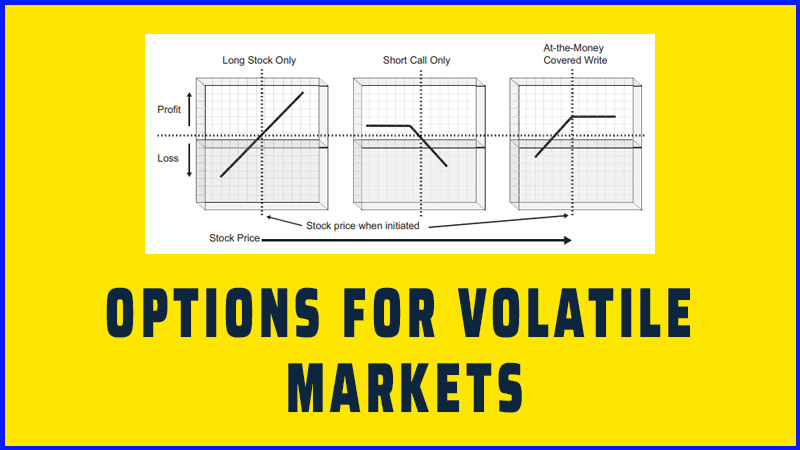

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 6: Basics of Put Hedging ]

Options |

Put hedging involves nothing more than the purchase of a put option on a stock you either own or buy simultaneously. The resulting position in both the stock and the put is often called a married put.

BASIC PUT HEDGING

Nowhere else in the investment world is

there anything quite like a put hedge. It is intuitively simple, highly

flexible, and can be easily implemented—or unimplemented. Depending on the

strike price of the put, the hedge can be implemented in such a way as to

provide almost any amount of downside protection on the underlying stock,

approaching 100 percent. With a hedging tool so effective, one might expect put

hedging to be a standard practice in portfolio management, but that remains far

from the case. While a substantial number of institutional managers flood in

and out of index puts to protect large portfolios when they sense the markets

are unraveling, they seldom utilize puts to hedge individual stocks, relying

instead upon broad-based stock and asset class diversification for reducing

risk over the long haul. This avoids the ongoing cost of put protection, but

leaves portfolios highly exposed and causes the ultimate fate of the

investments to rest on the manager’s ability to forecast disaster. (Indeed,

this is one reason why the 2008 decline still leaves the pension industry so

hugely underfunded.) But, to be fair, put hedging does have its drawbacks, and

unless the market truly experiences a major downside event, the cost of puts

can become a serious drag on upside performance. Nonetheless, as markets become

ever more volatile and as significant or catastrophic risk becomes more of a

concern (if not a reality), the put hedge (with variations we discuss in

Chapter 7) should not be ignored.

Put Hedge Basics

In its simplest form, put hedging

involves nothing more than the purchase of a put option on stock you either own

or buy simultaneously. The resulting position in both the stock and the put is

often called a married put. At one time, there may have been a distinction that

married puts were those in which the stock purchase and the put purchase were

initiated simultaneously (similar to the way a covered call write is considered

a buy-write if initiated simultaneously) but that distinction seems to be

somewhat blurred nowadays and does not impact the strategy. Since the put gives

you the right to sell the stock at any time before expiration at a

predetermined strike price, the put hedge serves as the equivalent of

purchasing insurance on the stock for the duration of that contract.

The elegance of a put hedge’s

simplicity is matched by its flexibility. As a result of the numerous strike

prices and durations of puts to choose from on each underlying stock or

exchange-traded fund (ETF), the choices are many. With monthly, quarterly,

multi-year and even weekly expirations available, and strike prices in 5-,

2.5-, and even 1-point increments, there are usually dozens of different put

options to choose from on a single stock. On some broad-index ETFs, that number

can easily get into the hundreds. Such flexibility offers investors and

portfolio managers the ability to decide almost precisely how much risk they

want to protect against and for exactly how long. No other hedging tool or

strategy comes close to that flexibility in equity investing.

While the straightforward put purchase

is simple and direct, the number of different ways to implement put hedging is

extensive. Besides the individual put purchase, there are combination

strategies that involve debit spreads, ratio spreads, butterfly spreads, or

calendar spreads. These strategies offer advantages in volatile markets because

volatility tends to make puts more expensive and these strategies reduce the

cost of the hedge. But they also come with trade-offs. For one, it is easy to

become overwhelmed by the myriad of possibilities; and for another, each

strategy has unique risk/reward characteristics that make them suitable for

some situations but not for others. Consequently, we strongly advise that you

establish your hedging need first and then zero in on an option strategy that

best meets that need. Questions to ask yourself include:

- What instrument (or combination of instruments) are you hedging, and why are you hedging rather than just selling it?

- How much of a decline do you wish to hedge?

- What is the probability of that scenario occurring?

- What time frame do you want to hold the hedge for?

- How much are you willing to pay for such protection or how much upside are you willing to forgo?

- Are you hedging against a potentially slow cascading decline or a quick drop-off?

Because of the cost—which will be

discussed further later in the chapter—the put hedge is rarely implemented (by

itself) as an ongoing strategy, and is most often utilized on an intermittent

basis on stock already owned. Generally, it would be implemented when a

stockholder or portfolio manager wishes to protect the downside against a

specific risk for a specific time period, but does not wish to sell the stock

because of taxes or because there may still be upside potential or a dividend

worth holding for. It is also not difficult to understand why put hedges aren’t

used very often, given that most stock pickers would find little sense in

purchasing a stock in the first place if they were that concerned about its

downside risk.

Since options aren’t available on all

stocks, and since large portfolios would find hedging individual securities

cumbersome to implement, a substantial amount of (if not most) put hedging is

implemented at the portfolio level, using index options. Lately, this concept

has expanded into puts on either sector-or broad-based ETFs as well.

But even when utilized as a form of

portfolio insurance, the purchase of put hedges is viewed as a temporary

strategy and usually implemented only when portfolio managers deem that there

is greater risk in the market than usual. Otherwise the cost of the put weighs

against performance and places the manager at a competitive disadvantage in all

scenarios where the stock does not go down significantly. But the rush to buy

portfolio insurance after a news event like deteriorating economic fundamentals

or North Korea firing on South Korea causes the manager to pay a higher price

for the puts as the demand increases from tens of thousands of others thinking

the same thing. In so doing, the manager becomes a market timer just as clearly

as if they had liquidated or reduced the portfolio itself. Furthermore,

intermittent buying of puts on portfolios whenever perceptions dictate is a

flawed strategy since the put purchases usually don’t even begin in earnest until

a decline gathers momentum, and will also miss large surprise moves that simply

occur before a decision to buy puts can be made.

There are, however, valid reasons for

the simultaneous purchase of stock and a put option, such as when you are

trading on the expectation of an announcement that will either be really good

news or really bad news and you want to limit your loss, or when you purchase a

stock like British Petroleum (BP) after the Gulf disaster when you feel it is

extremely cheap, but want protection against further unforeseen liabilities

that may yet arise for the company.

In concept at least, put hedging

provides a way to create an equity portfolio with as little or as much risk as

one is willing to absorb. Covered call writing could then be layered on top to

provide more predictable upside returns. By using options in this manner, it

thus becomes possible to create a hybrid investment between a stock and a bond

with risk/reward characteristics that are somewhere in between.

Table 6.1 Basic Put Hedge at Three Different

Strikes

|

Buy (or own) 100 XYZ at $50 Buy 1 XYZ 3-month put at strike

prices of 45 (OTM), 50 (ATM), and 55 (ITM) Duration = 60 days Volatility = 25 percent Interest rate = .5 percent |

|||

|

|

OTM |

ATM |

ITM |

|

Stock price |

50 |

50 |

50 |

|

Put strike price |

45 |

50 |

55 |

|

Put cost (dollars per share) |

.37 |

2.00 |

5.47 |

|

Insurance cost (as a percent) (cost

of the time value in the put) |

.74% |

4.0% |

.94% |

|

Maximum risk |

5.37 |

2.00 |

0.47 |

|

Upside potential |

Unlimited |

Unlimited |

Unlimited |

The practicalities, however, of

creating a portfolio solely of stocks with options listed on them and managing

the risks and opportunities of each position through put hedges and covered

calls are still somewhat challenging. But the advent of ETFs brings us closer

to solving that issue as well. This will be further discussed in Chapter 8.

Meanwhile, Table 6.1 provides

examples of a basic put hedge at three different strike prices to examine how

much the varying degrees of protection cost.

Note that when we talk about the “cost”

of a put hedge, we do not consider the entire option premium paid for the put

to represent the cost if the option is in the money. A more realistic way to

look at it is that the cost of a put hedge is the amount of money you will pay

(and not recover) if your stock remains at the current price. In other words,

it is only the time value of your put purchase. Any intrinsic value that is

part of the put premium will be part of the outlay for the put, but is actually

a purchase of additional value on the underlying stock rather than a cost of

the insurance on that stock—and it will be recovered at expiration, either

through exercise or by selling the put. In this example, the ITM put hedge

involves the purchase of a put at the 55 strike for 5.47. Though you spend $547

for that put, $500 of it is purchasing additional value on your stock, because

exercising the put would result in your receiving $55 rather than the $50 your

stock is currently worth. Therefore, you will have spent $47 per hundred shares

of stock for the insurance. (More on cost follows—see Figure 6.1.)

Figure 6.1 Basic Put Hedge at Three Different Strikes

Advantages

The basic put hedge has a number of attractive

qualities for investors seeking downside protection.

- Conceptually simple. You simply purchase one put contract for each 100 shares of stock or ETF that you wish to hedge. Buying a put option guarantees you a minimum price in advance for your stock, and you determine that price through the selection of the put. Your guarantee comes from the Options Clearing Corp.

- Can be turned on or off as desired. The beauty of a listed, standardized market for options is that once purchased, you can decide for any reason to cash in your put contract early, in which case you simply sell it at the going price in the market. In this manner, you turn the insurance on or off at any time as desired (subject, of course, to transaction charges and current market prices). For those wishing to insure their stock holding for a specific event, such as a major news announcement or product introduction, the put hedge can be implemented only while needed and redeemed later to recover at least part of the cost or potential profit.

- Easily tailored to offer as much downside protection as desired. Put hedges can be designed to protect against almost any magnitude of decline, up to nearly 100 percent. They can also be implemented only for catastrophic protection or for protection beginning at a certain price.

- Offers lots of flexibility on strike price and duration. There are always options in at least four different months and at numerous strike prices to choose from.

- Provides single security protection. Puts are the only hedging tool that can be directly applied to an individual stock. (Some stocks may have single stock futures, but these are not widely available.)

- Still leaves upside potential. The cost of the put reduces your net return from the stock, but still enables you to realize a theoretically unlimited upside gain on your stock position.

Disadvantages

There are a number of disadvantages to

put hedging, though we consider them better viewed as trade-offs, since they

tend to impact how the strategy is implemented rather than whether it is at

all.

Cost

The biggest drawback of the put hedge

is its cost. While the cost of a single put option generally represents a small

fraction of the value of the underlying holding (and that insurance could be

worth many times its cost should the stock tumble far enough), the price of downside

protection through put hedges is not cheap and can represent a significant drag

on upside performance. The cost can easily become prohibitive when incurred

over an extended period of time. Cost also varies quite a bit with strike price

and with the volatility of the underlying stock, so these factors are very

significant to implementing the strategy, and are explained in greater detail

below. If you purchase a put when your underlying stock is already falling or

widely anticipated to fall, the price may be even more expensive as the implied

volatility may rise, and all puts will also cost more during periods of high

volatility or high interest rates.

As noted above, we consider the cost of

a put hedge to be the time value of the option purchased, as that is what you

will not recover if the stock remains where it is at expiration. Thus, in Table 6.1, we figure the cost of the

ITM put as a low .47 because the other 5.00 is recoverable at expiration. That

$5, however, represents another issue related to actual cost—opportunity cost.

The opportunity cost—the entire amount of upside opportunity that is

potentially forgone through a put purchase—is the full premium paid for the

put. This opportunity cost represents the drag on upside performance that is

largely what makes the put hedge so unattractive to professional managers. In

the ITM example above, if the stock were to go up to say 53 by expiration, the

manager who had purchased the 55 strike puts would show a return of —.94

percent for the period, while a nonhedged manager would show a gain of 6

percent.

The cost of a put hedge varies

considerably with three primary factors: duration, strike price, and

volatility. (As with call options, interest rates and dividends also affect

price, but to a much lesser degree.) Deciding whether to employ a put hedge,

and if so, which put to select, requires an understanding of these factors.

Duration

One would certainly expect to pay more

for a longer duration put hedge, given that more distant options cost more. But

remember that the relationship between price and time for options is not

linear. Price varies instead as the square root of time. So a put hedge with

six months’ duration will not cost double that of three-month hedge. The longer

the duration of an option, the less time premium it has per day. For put

hedgers, this means that buying a series of one-month puts to protect a stock

over say six months would cost a lot more than having purchased a single

six-month option to begin with. Table 6.2 and Figure 6.2 illustrate.

Volatility

Just as you pay more over time to

insure your house if you are in a more risky environment like a flood plain,

you can expect to pay up for puts on stocks with higher volatility.

TABLE 6.2 Cost of an ATM Put Hedge versus

Duration

|

Volatility |

30 Days |

90 Days |

120 Days |

240 Days |

360 Days |

|

20

(similar to S&P 500 index) |

28% |

16% |

14% |

10% |

8% |

|

30

(similar to Boeing) |

42% |

24% |

21% |

15% |

12% |

|

45

(similar to Freeport McMoran) |

62% |

36% |

31% |

22% |

18% |

Note: Annualized cost of an ATM put hedge on a

$50 stock at various volatilities expressed as a percentage of the value of the

underlying.

FIGURE 6.2 Cost of an ATM Put

Hedge versus Duration

Put hedges will always cost more on

stocks with higher volatility, though the relationship between price and

volatility is somewhat complex depending on the strike price of the option. As

a guideline, however, ATM options vary linearly. Thus, if you compare ATM put

options (which have only time value) on two $50 stocks where stock A had twice

the volatility of stock B, the puts on stock A would be twice the price of

those on stock B. That makes it challenging to use a straight put hedge strategy

on high-volatility stocks, as it will cost accordingly more to do so.

Importantly, put hedgers must also

recognize that volatility (both actual and implied) changes over time, even on

the same stock. That means a 30-day ATM put hedge on XYZ won’t always cost the

same amount, even if the stock is the same price. You might see a considerable

difference in the price of puts on the same stock over time as volatility

changes, and it is not uncommon to see implied volatilities differ by a factor

of two or more between two different time periods on the same stock. This can

happen due to the stock’s individual character (i.e., earnings, news, etc.) or

because the entire sector or market as a whole is experiencing a change in

implied volatility.

Changing volatility doesn’t just affect

the cost of a put hedge in different time periods, it affects the price of your

put hedge while you own the stock and the put as well. You may, for example,

buy a put during a period of high implied volatility, and then see the stock

decline only to find out that your put did not have the offsetting gain you

expected. Of course, you could be surprised in the other direction also, if

your put goes up even more than you anticipated. Volatility, therefore, is

essentially a moving target, and one that is very challenging to predict.

As you can see from Table 6.2, buying an at-the-money put

on a $50 stock (assuming an implied volatility similar to a stock like Boeing)

with a one-month duration would cost you 42 percent of the stock’s value on an

annualized basis (meaning that’s what it would cost over the year if you

theoretically bought one every month), even at today’s very low short-term

interest rates. Clearly, this is prohibitive for someone looking to keep a put

hedge on for any length of time. Even the 12 percent that it costs using a

single one-year LEAPS put represents a substantial drag on upside performance.

Higher volatility stocks only make the

cost of a put hedge even more prohibitive. To hedge a stock like Freeport

McMoran, it could cost between 18 and 62 percent annualized depending on the

option used in the previous example. In this table, since all the options are

at-the-money and have no intrinsic value, you can see how the theoretical

prices vary linearly with volatility. You may be thinking that if the cost is

so outrageous, maybe selling puts makes a lot more sense than buying them. As

an ongoing strategy, you might be correct in that conclusion, but we are

specifically looking to hedge a stock or ETF here—shorting puts is a different

strategy and is covered in Chapter 5.

Strike Price

It stands to reason that the higher you

want the right to sell your stock for, the higher the price of the option that

gives you that right. Accordingly, the higher the strike price of the put, the

more it will cost. Conversely, the lower the strike price, the less insurance

you are actually buying and the lower the price of the put. In the same way

that you pay less for insurance when there is a deductible amount, you pay less

for the lower strike put, because the insurer isn’t going to pay the full

claim—you’re absorbing at least some of the risk. If you own stock at 65 and

buy a put at the 60 strike, you’re absorbing the first five points of loss,

just as you might pay the first $250 of an accident claim on your vehicle.

Table 6.3 shows theoretical prices for a 90-day put option on a $50

stock at various strike prices and Table

6.1 showed the risk/reward for OTM, ATM, and ITM put hedges.

When you are considering which strike

price to purchase for your put hedge, you are making a strategic risk/reward

decision. If you have a $50 stock and you are concerned it might drop to 45 on

potentially bad news, buying a $50 put will help offset part of that potential

loss, but buying a $45 put could end up offsetting little or none of that loss,

though it only cost you $.35 per share.

Table 6.3 Cost of a Put Hedge at Different

Strike Prices

|

XYZ = 50 Volatility

= 20 percent Duration

= 90 days Interest

rate = .5 percent |

|

||||||

|

|

|

Strike

Prices |

|

||||

|

|

40 |

45 |

50 |

55 |

60 |

||

|

Put price |

-2.5 |

+2.5 |

+2.5 |

+2.5 |

10.5 |

||

|

Cost of

hedge (time value only) |

0 |

+5.0 |

0 |

-5.0 |

.25 |

||

Should the stock drop to say 46 at

expiration, you will have lost $4 per share and yet still own a put hedge that

expires worthless. If you wanted to hedge most of the anticipated $4—$5 decline

on the stock, you would need to purchase a $55 put. You would spend $5.44 per

share, but should the stock drop to 46 in that scenario, you would have an

option worth $9, gaining almost all of the value you lost in your stock (less the

$.44 you originally paid in time value). The trade-off in that situation is

that if the stock rose instead of declined, to say $54, then you receive little

or no benefit from that rise.

Efficiency

A put contract guarantees you a floor

price for your stock, which you can count on for as long as the option exists,

but it does not guarantee that a loss on the stock will be completely offset by

the put in the interim. As the stock or ETF goes down, your put is likely to

gain value, but the profit on the option is going to be less than the amount by

which the stock has declined and less than you would receive if held to

expiration. How much less will depend on the option strike, the time remaining,

and the change, if any, in the implied volatility of the option. In a general

way, this describes the efficiency of a put hedge—how much it will actually

offset a drop in price in the stock. The efficiency of a put hedge should be an

elementary consideration when implementing the strategy, even if only to

establish an expectation for the dynamics of the position and to help determine

which put option best meets your objectives. The word efficiency is used here

as a descriptive term, rather than as a specific measurable item. There are,

however, measurable aspects of an option’s efficiency. The most important of

these is the option’s delta.

Delta, one of the Greeks (Greek letters

that are used to quantify certain option characteristics), is the amount an

option is expected to move for a one dollar move in the underlying stock. Delta

is frequently calculated for you and presented as one of the key columns in

many option chains. The delta of a put can vary from zero to one depending on

how far in-the-money it is and how much time is left before expiration. But

since delta depends on both price and time, it changes as soon as either of

those two variables changes. That makes it a bit of a moving target, but gives

you a ballpark idea of how an option will react to a given price move on the

stock. Deltas for put options are expressed as negative numbers since the value

of a put is inversely related to the price of the underlying stock.

As an example, let’s say the delta for

a put option at the 30 strike when the stock is 30, volatility is .30, and

there are 60 days remaining before expiration would be —.47. That means if the

stock drops to 29, the 30 strike put should increase in value by $.47. But as

soon as the stock moves to a different price or as days until expiration

decrease, delta changes as well. Thus, the second dollar move has a slightly

different delta and so on. Consequently, one may not necessarily conclude in

this example that if the stock dropped five points, that the option would move

.47 x 5 = 2.35 points. In the case of this drop, the option would theoretically

pick up 2.55 points, since the option was moving into the money more with each

dollar drop on the stock, so that the option’s delta was increasing a little

with each dollar of decline on the stock. Similarly, a four-point rise would

cause the option to drop only 1.36 points as it would become further out of the

money for each dollar the stock rises and the delta would decrease for each

subsequent one-dollar move.

Figure 6.3 illustrates the theoretical change in an option’s price for

various price changes in the underlying stock on the same day, using the

example shown.

The relationship between delta and both

time and price is complex. The key thoughts to take away from this analysis are

as follows:

- OTM puts are going to be rather inefficient as hedges until the stock falls enough to bring them into the money.

- The delta of an ATM option is going to be close to .5 in any time horizon. So, for OTM options, the delta will be somewhat less than .5 and for ITM options, the delta will be greater.

- The inefficiency of OTM put hedges gets better for ITM options as expiration approaches, but worse for OTMs.

FIGURE 6.3 How Option Delta

Changes with Time and Stock Price

The bottom line is that to obtain

anything close to a dollar-for-dollar hedge on a stock, one would need to

either buy a deep-in-the-money put with a very high delta, or buy more puts

than there are shares of stock (i.e., a ratio hedge.). If you have a put option

with a delta of —.5, for example, then you would need twice as many puts as you

have round-lot shares of stock to make sure you were properly hedged for a

one-dollar move.

Tax Considerations

Options that are purchased and later

sold or expire within one year (as the great majority are) are subject to

short-term capital gains or losses accordingly. As with covered calls that are

assigned, there is no closing transaction to a put purchase when it is

exercised, so in that instance, the put purchase gets added to the cost basis

on the stock for tax purposes. But (as they also do for certain covered call writes),

the IRS views the purchase of a put hedge to sufficiently reduce the risk of a

stock position as to constitute a short sale. This results in put hedgers

having to be alert to the “constructive sale rule” and

the “anti-straddle

rule” as defined by the tax code when

reporting gains and losses on the underlying stock positions. A resulting issue

with regard to put hedges is that for stocks held less than one year, a put

purchase on that stock will wipe out the holding period on the stock for

long-term gain purposes, and the clock will not start again for the stock until

the put hedge is closed. (If the stock is already held more than one year, the

put does not affect its long-term status.)

Those using puts to hedge in qualified

retirement accounts like individual retirement accounts (IRAs) need not worry

about the tax intricacies mentioned above, but those using puts to hedge in

taxable accounts are ad-vised to check with their tax advisor or consult the

IRS for the latest rules on the taxation of put hedges.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 6: Basics of Put Hedging : Tag: Options : Put Hedging basics, Advantages of put hedge, Disadvantages of put hedge - Options Trading: Put Hedging basics

Options |