Options Trading: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques

Define Partial Writing, Define Mixed Writing, Define Ratio Writing, Define Put Writing, Define Expiration Games, Define Option-Stock Arbitrage

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 5: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques ]

Options |

More advanced strategies exist that involve writing more or fewer than one call per 100 shares of stock or writing calls in different series. Generally speaking, these strategies apply to larger portfolios, where thousands of shares of stock are involved, though they can be implemented with even a few hundred shares.

Partial Writing, Mixed Writing, and Ratio Writing

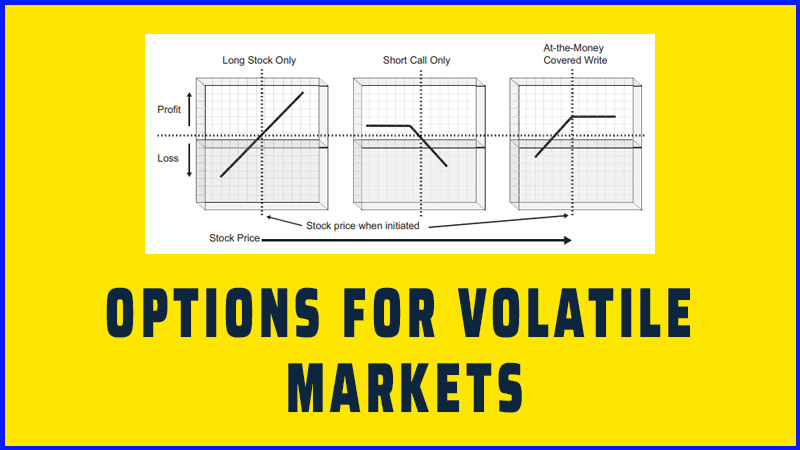

Discussions thus far have assumed a

one-to-one relationship between stock owned and calls written. They have also

assumed that all calls written on one stock are from the same series (same

month and strike price). More advanced strategies exist that involve writing

more or fewer than one call per 100 shares of stock or writing calls in

different series. Generally speaking, these strategies apply to larger

portfolios, where thousands of shares of stock are involved, though they can be

implemented with even a few hundred shares. In smaller portfolios, the added

complexity and commissions could negate the benefits gained.

Partial Writing

Partial writing is a conservative mode

of implementing an incremental return strategy. You might employ it if you hold

at least 600 shares of a particular stock and want some incremental return from

option premiums but don’t want to have shares called away until the price rises

much higher. You would start by writing calls on part of your position with the

intention of rolling the position up (and possibly out) if the stock rises

above the initial strike price. By writing on only part of the position, you

are taking in incremental option income while building in room to roll for a

credit if the stock reaches the initial strike price. That is, writing against

only a fraction of your shares to begin with gives you the ability to roll not

only up to a higher strike price or out to a more distant expiration but also

to a position that consists of more contracts and still be fully covered.

You may not need that room, but it

gives you the confidence that even if the stock moves up sharply, you will be

able to roll without getting assigned at too low a strike price and without

having to put in any additional money. Since you are assured that you will not

be called away until your ultimate target price is reached, whatever you get

from all the call writing is purely incremental.

You have to do some calculations and

consider some what-ifs to figure out how best to implement a partial writing

strategy, and you will not be able to make it work for a target price that is

too high. Effective implementation may depend on how far above the strike price

the stock goes before you roll.

Say you own 1,500 shares of OPQ, which

is trading at $56. You do not want to sell at less than $70, but no 70 strike

price is yet available, or if one is, it has too little premium. You begin by

writing four calls at the 60 strike in a relatively near month. If they expire

worthless, you can write the same strike again for the next month. If the stock

moves up to between $60 and $65 after you’ve written your calls, you could roll

to the 65 strike. To insure you receive a credit, you could write up to eight

of these calls. That way, even if the premium is half that of the 60 strike,

you can still roll without putting in additional money. You can also move out

to a more distant month. If the stock moves beyond $65 to near $70, you might

roll up to the 70 strike. You could now sell up to 15 calls at the 70 strike

with the confidence that you would receive at least $70 for your stock if

assigned. Plus, you keep all the option premiums you accumulated along the way.

This strategy requires that you monitor

your positions and roll your options accordingly. You will probably also want

to recalculate the size of your call position as the stock moves or as your

target price changes. Also, note that your stock could eventually move up to a

high enough price to preclude you from rolling for a credit. While this should

be very good news for the value of your underlying shares, it might require you

to take a loss on one of your call writes unless you are prepared to accept an

assignment. Should this occur, however, you would likely be way ahead of where

you would have been if you had not been writing any calls on the position at

all.

Mixed Writing

Mixed writing simply involves dividing

your covered calls between two or more strike prices, expiration months, or

both on the same stock. It is yet another example of the versatility of covered

writing and a way to tailor the strategy to your specific needs. By writing

calls with different strike prices, you can split the difference to fine-tune

your breakeven point or ultimate target price for the stock. Allocating calls

between two or more expiration months can also enable you to distribute premium

income more effectively throughout the year. This is particularly useful when

you have an abnormally large position in a particular stock.

Say you purchase 600 shares DEF at $45

a share in January when the February 45 calls on DEF are selling at 2.50 and

the February 50 calls at 1.15. You may feel that writing the 45 strike calls

leaves too little upside in the stock, while the 50 strike calls offers too

little premium. To produce a risk/return you are more comfortable with, you

decide to write three contracts of each option against your long position in

the stock.

TABLE 5.5 Returns from Mixed Call Writing

|

Buy 600

DEF at $45 and Sell |

Net

Investment (Breakeven Price) |

Return if

Unchanged* |

Return if

Exercised* |

|

6 DEF Feb

45 calls at 2.50 |

$25,500 |

5.6%

|

5.6%

|

|

6 DEF Feb

50 calls at 1.15 |

$26,310 |

2.6% |

13.7%

|

|

3 DEF Feb

45 calls plus 3 DEF Feb 50 calls |

$25,905 |

4.1% |

13.7%

|

* Returns are calculated on the stock

investment of $27,000 and exclude commissions.

Table 5.5 compares the results for the two individual writes with

those for the mixed write.

If you mix covered calls with expirations

in different months, the analysis becomes a bit more complicated, but the

concept is the same. You’re either fine-tuning your upside potential between

two (or more) strike prices for a given month, or you are hedging your position

between two (or more) time periods. The important point is that with mixed

writing, you have even more flexibility than with single strike prices and

expiration months (Table 5.5).

The technique of spreading your covered

calls over different expiration months is applicable not only to individual

stocks but to an entire portfolio as well. You might sell one- or two-month

options against one-third of your portfolio, three- or four-month calls against

another third, and still longer- term calls against the final third. The rationale

for this would be to spread the call writing over the calendar year to insure

that you are not writing them on an entire portfolio at a time when market

volatility and/or prices are low.

Ratio Writing

Aggressive call writers who believe a

stock will remain within a defined price range or perhaps even decline will

sometimes write more than one call per 100 shares of stock held. This practice,

called ratio writing, adds an open-ended risk component to the basic covered

writing strategy, since the additional calls are naked.

Ratio writers might sell 1.5 or 2 times

as many calls as they have round lots of a particular stock—writing 9 or 12

calls, for example, against 600 shares owned. The rationale is that if the

stock remains flat or declines, the writer pockets that much more premium than

on a simple covered write. This provides more downside protection, but at the

expense of a new risk on the upside. Should the stock rise beyond the strike

price (assuming for the moment that all of the calls are at the same strike),

the writer makes the maximum gain on the covered part of the position and would

have the stock called away. But the additional short calls must be bought back,

possibly at a loss. The writer would first give back profit made on the covered

write and then premium earned from the sale of the additional calls before

starting to lose money overall. But the risk on the upside is still

theoretically open-ended. In addition, the uncovered calls would require

margin, which reduces the buying power of the account.

Figure 5.1 shows the risk-reward profile of a 2:1 ratio write compared

with that of a regular covered write. The inverted V of the ratio write’s

profile, which shows how the strategy offers profit both above and below the

strike price of the options, can be designed to coincide with a standard

probability distribution curve for a given stock. In fact, as will be discussed

in Chapter 9, you can calculate the probability of a stock being inside the

profit range of any ratio write, given its projected volatility.

If you like the concept of a ratio

write but are uncomfortable with the open-ended risk on the upside, you can cap

the risk by buying calls with higher strike prices than the ones you have

written in sufficient quantity to cover those that are naked. In other words,

you create a credit spread on the naked calls. Of course, this adds to the cost

of the strategy, reducing profits all along the profit curve. Say, in the

example in Figure 5.1, you bought one XYZ Nov 55 call at 0.75. Your maximum profit

on the position drops to $525 from $600.

Figure 5.1 Risk/Reward for 2:1 Ratio Write

But the unlimited potential risk is

removed. The worst case on the upside now leaves a profit of $25 before

transaction costs for all prices above $55 on the stock. This does not alter

the downside risk of the underlying stock position, although it does lessen

both the maximum gain and the protection provided by the original ratio write

by the amount paid for the long calls.

For a small cost, this represents an

easy way to employ a ratio write strategy without incurring the unlimited

upside risk of the additional naked calls. But, remember, as the stock goes up

you make money from the covered write and then lose that profit back to the

spread if the stock keeps going, so you are going to make a profit over a

decent range of stock prices (55.8 to 64.2 in the following example). Thus, as

you can see from Table 5.6, the strategy is still very attractive in price

scenarios near the current price and has little or no upside risk.

Additionally, you can see how the ratio

write (with or without the additional long call) provides more downside

protection than the straight covered write and more return in the unchanged

scenario. As such, it is more effective as a static or defensive strategy. It

will, however, underperform when the underlying is rising strongly.

TABLE 5.6 Profit/Loss of Covered Write versus

Ratio Write

|

ABC stock = 60 ABC March 60 call = 2.50 ABC March 65 call = .80 |

|||||

|

|

|

Profit/Loss |

|||

|

Strategy |

Position |

At 55 |

At 60 |

At 65 |

At 70 |

|

Covered Write |

Long ABC Short Mar 60 Call |

-2.5 |

+2.5 |

+2.5 |

+2.5 |

|

Ratio Write |

Long ABC Short 2 Mar 60 Calls |

0 |

+5.0 |

0 |

-5.0 |

|

Ratio Write with Spread |

Long ABC Short 2 Mar 60 Calls Long 1 Mar 65

Call |

-.8 |

+4.2 |

-.8 |

-.8 |

Put Writing

Few people tend to realize that selling

put options is a direct strategic alternative to covered call writing with

virtually identical risk/reward characteristics. The risk/reward graphs of the

two are identically shaped, and both strategies make a limited amount of money

on the upside while incurring the downside risk associated with owning stock.

A put writer is obligated to purchase

the underlying stock at the strike price if the option holder exercises. Say

you write the June 20 put on ABC stock when it is trading at $22, earning two

points in premium. You are now obligated to buy the stock at $20 if assigned,

but the two points you have received from the put sale make your actual cost

basis on the stock $18, excluding commissions. That means you make a profit for

all prices above $18 at expiration. Put writing is therefore a

neutral-to-bullish strategy, just like covered call writing.

When writing put options, you do not

need to cover the option with a stock position to prevent an unlimited risk,

though you do need to put up either cash or margin. That’s because the open

risk of a naked put is on the downside and is no greater than the risk of

owning stock or writing a covered call. If you are assigned, you simply buy the

stock and incur the normal downside risk of owning it. You can cover a put

option by shorting stock or by buying another put option and creating a spread,

but those are different strategies. The main point is that naked put writing

can be viewed as a twin strategy to covered call writing.

Advantages

The biggest advantage put writers have

over covered call writers is that they put up much less money. When writing

puts, you are required to set aside margin, either as cash or the margin value

of other securities. The margin requirement for a naked put is 20 percent of

the stock price, less the amount by which the put is out of the money, plus the

put premium, subject to a minimum of 10 percent of the stock price. (The

premium taken in can be applied against this requirement, or it can be put in a

money market fund to earn interest.) That’s a much smaller outlay than you

would make in buying a stock for a covered write, even when the purchase is

fully margined. Plus, there is no margin interest involved. Also, put writing

involves only one trade execution instead of the two required in covered call

writing. That means less commission and only one bid-ask spread to deal with.

Taking the same example presented in

the preceding discussion, by writing the put at the 20 strike with ABC at $22,

you are essentially saying that you are willing to buy the stock at a net price

of $18 if it pulls back. You are also saying that if it doesn’t pull back by

expiration, you’ll be happy to pocket two points for your trouble without ever

having to own the stock. As a put writer, you collect premium, tying up

reasonably little money or simply using the margin power of your existing

portfolio, and will have to buy stock only if the price goes down. If the stock

does decline, you can roll or close your position before being assigned, just as

the covered call writer can. (Since naked puts are a single-security strategy,

closing a position entirely, even at a small loss, is easier than with covered

call writing and, as has been noted, involves lower commissions.) Or you can

simply wait to be assigned, buy the stock, and then perhaps write calls against

it.

Strategically, put writing actually

fits certain situations better than covered call writing. Say there is a stock

that you would like to own but that has already seen a run-up in price. You might

be concerned that it is too highly valued to serve as the underlying in a

covered write. In that case, you should consider selling a put option on it

instead. That way, you make money if the stock continues to rise, and you buy

it only if it pulls back to a more reasonable price—the strike price of the

put. A major disadvantage of this approach is that if the stock has fallen

substantially below the strike when it is put to you, you might not be very

happy owning it. Of course, you would suffer the same disappointment in a

covered write. With puts, the biggest disappointments tend to be when the

underlying stock goes way up, and the most you make is the premium you received

from selling the put option.

Disadvantages

Put writing is a naked option strategy,

so the requirements from your broker will involve a higher-level option

approval and greater minimum account equity, perhaps on the order of $25,000.

Put options also carry slightly less premium than equivalent calls (those

having the same strike price and expiration) and can be slightly less liquid.

And since you do not own the stock (unless assigned), you will not receive

dividends. Remember as well that if you are assigned, you will need to have the

capital or the margin power to carry the stock position, which will be greater

than the 20 percent required to carry the naked puts themselves.

Because of the leverage involved in

selling puts and the fact that you can implement the strategy with no cash or

margin debit (it uses margin but does not create a debit balance), it is easier

to overextend yourself with put writing than with covered call writing.

Brokerage houses are aware of this, which is why they impose additional limits

in the form of margin requirements or minimum account equity. You therefore need

to maintain a sound perspective on the size of the positions and the type of

stocks on which you write puts.

Efficiency, Inefficiency, and Overvaluation

Which makes the better covered write:

the May 30 call on ABC stock selling at 1.75 when the shares are trading at

$30, or the May 30 call on DEF stock selling at 3.5 with the shares at $30? The

answer is: You cannot tell from the information given. Certainly, DEF has the

greater potential return if exercised and if unchanged. But it should also have

the greater downside risk, since the price implies higher volatility and,

theoretically at least, volatility is directionless. You also don’t know which,

if either, of these options is overvalued.

In a perfect world, the implied

volatility of the two options above would be a true representation of the

stock’s future movements, meaning the options would be perfectly priced to

account for the difference in the underlying volatilities, and the expected

returns of the two covered writes would be equal. (Expected return is the

average return one could theoretically expect if this action were repeated a

large number of times.)

As we all know, however, the world is

not perfect, and neither is the options market. Option buyers frequently pay

more than an option is theoretically worth because, even at that higher price,

the contract still represents a tremendous amount of leverage. This logic is

false. The ability to sell an option at a profit does not alter the fact that

it may have been overvalued when purchased. Overvaluation embodies the

statistical premise that over a great number of such situations, options that

are priced higher than their theoretical values will turn out to be more

profitable as sales than as purchases if held until expiration.

Published statistics on the effect of

overvaluation in options are scarce. However, if the Black-Scholes formula is

valid and option overvaluation is indeed due to the occasional willingness of

buyers as a group to overpay, then writing overvalued options is advantageous over

the long term. The real key, then, to finding the best covered writes is not

just looking for high premiums. It is finding situations where the option is

forecasting a higher volatility in the future than the stock will actually

exhibit—where it is, in other words, overvalued. Overvaluation in this sense is

theoretical, since the only way to determine what is overvalued is to know what

the future volatility of a stock will be. In the absence of a crystal ball, how

does one do that?

There is no standard solution to these

problems among investment firms, and different approaches can be rather

complex. The one presented here is that used by Lawrence McMillan at McMillan

Analysis Corporation, an advisory firm that specializes in option strategies.

McMillan searches for options that

appear overvalued relative to their own history of implied volatilities and to

actual historical volatilities, as opposed to the Black-Scholes theoretical

price. The first step in this process is to calculate three historical volatilities

(20-, 50-, and 100-day) for all stocks with listed options to get a sense of

whether their volatility has been increasing or decreasing and by how much.

Next, the firm weights each option’s implied volatility according to its

trading volume and its distance in or out of the money, with the heaviest

weighting given those with the highest volumes and strike prices closest to the

current share price. The weighted figures are averaged to arrive at a composite

implied volatility for the stock, which is then compared with the composites

calculated for up to the past 600 days to determine what percentage of these

the current composite is greater than. A percentile rank of 95, for instance,

means that the current composite implied volatility is greater than 95 percent

of those calculated for the past 600 days (or as many days as the data are

available for). By itself, this statistic is of little use to most investors.

But as a comparative measure, either to other stocks or to other time periods

for the same stock, it can be very useful in deciding whether a covered write

on that stock offers an attractive risk/reward situation. Current figures on

volatilities are illustrated in Table

5.7.

Covered writes and spreads can be used

to capitalize on such disparities, but only with the understanding that the

statistical advantage shows up over time. For covered writers, the lesson is to

check a number of different options when looking for the best one to write on a

given stock. And if there’s a skew, try to determine the reason—whether it’s

news or event driven, for example.

Expiration Games

Anyone who uses option strategies

becomes acutely aware of the importance of expirations. On the last trading day

(Friday) before an expiration day, a variety of cross currents operate on both

options and their underlying stocks. On top of all the normal buying and

selling are activities specific to the expiring options. Sometimes these are

non-events; other times they have a visible effect on the day’s trading volume

and price movements.

It is impossible to predict exactly

where a stock will close on the Friday before expiration. You can, however, get

some clues from the options as

Table 5.7 Sample 20-, 50-, and 100-Day Historical Volatilities

* Number of days of data and percentile

ranking of current implied volatility to full range of implied volatilities

during that period.

to the forces that may affect the

stock’s price that day. Open interest is the key. If the open interest in

expiring put or call options is small—that is, in the hundreds of contracts—it

will put little pressure on the price of the stock in either direction. On the

other hand, if thousands or tens of thousands of expiring options are in the

money on Friday, there could be a heavy supply of options for sale, since most

holders prefer to sell rather than exercise. The buyers of these options will

primarily be the market makers on the exchange floor, since they are obligated

to provide a market, and they will be looking to hedge their positions with the

stock.

Say that 10,000 call options in XYZ at

the 40 strike price are expiring, and the stock is trading at $40.65. Many

holders of these options will be selling to close out their positions. Market

makers will be buying them and exercising to get the cash value. These market

makers will likely sell the stock short when they buy the call, to lock in the

current price. Then, over the weekend, they will exercise to buy stock at the

strike price, closing their entire positions. Because this process involves the

market makers selling stock during the last trading day, it tends to push the

stock price down toward the strike price in the final hours of trading.

Put option open interest could presage

the opposite process. If the stock is trading just below the strike price and

put open interest is large, holders will sell their puts as a closing

transaction. The market makers buy the puts, then buy stock to hedge, and

finally exercise the puts to sell stock and close out the whole position. The

market makers are buying stock in this case and thus pushing the stock back up

toward the strike.

The net effect, when the size of open

interest in puts is close to that in calls, is a tendency to drive the price of

the stock toward the strike price when it is already close to it. Evidence of

this phenomenon has been found in academic studies. In one such study, a sample

of nearly 1,000 expirations showed that stocks closed within $1 of a strike

price about 40 percent of the time (exactly what a random distribution would

predict), but within $0.50 of the strike price 28 percent of the time (compared

with the 20 percent that a random distribution would predict).

When stocks are wavering back and forth

around a strike price at expiration, both holders and writers are on edge. If

you’ve written calls on XYZ at the 40 strike and the stock is trading between

$39.75 and $40.25 on the Friday before expiration, you could well be torn

between doing nothing and rolling the call to the next month to prevent being

assigned. Both tactics can be valid, depending on your desire to hold the stock

and rewrite as opposed to losing the stock and having cash to reinvest. The

best approach is either to decide a few days earlier what your plan will be or

else to simply accept whatever happens in the final trading session.

Option-Stock Arbitrage

In Chapter 2, we discussed option

pricing and referenced the fact that arbitrage keeps the prices of puts and

calls in line with the stock in the same month. We include here a more detailed

explanation of this arbitrage. The inclusion of a section is not intended as an

endorsement of the practice by individual investors but rather as an aid in

understanding the forces at work in the options marketplace. Arbitrage as it

applies to equity options exploits the relationship between the price of the

stock and the prices of both the put and call options at a specific strike

price.

Arbitrageurs can effect a riskless

transaction by purchasing a stock and then buying a put and selling a call on

it, with both options having the same strike price and expiration. This

combination is called a conversion. (The opposite, a short stock, short put,

long call position, is called a reversal.) Example:

Buy GHI.

Buy GHI Jan 70 put.

Sell GHI Jan 70 call.

Implement all three positions for a

cost under $70.

Upon expiration, if GHI is above $70,

the stock will be called away for $70. If the share price is below $70, the

arbs can exercise the put to sell the stock at $70. In other words, regardless

of where the share price ends up, the arbs can get $70 for the stock at

January’s expiration. Once the conversion is implemented, the profit is

guaranteed, and there are no commissions, since arbitrageurs are exchange

members, but there is a cost for carrying the net position. That’s where

interest rates affect option prices. Arbs will put on the position if the

profit they can lock in is greater than the cost of carry. So when interest

rates are higher, arbs must generate a higher gross profit, meaning they will

either have to receive more for the call or spend less on the put relative to

what they pay for the stock.

This arbitrage helps maintain a

relationship between the puts and calls with the same strike price and

expiration month on a given stock. If demand for the GHI January 70 calls in

the example increases without an attendant rise in the stock or in the January

70 put, their price might begin to rise, providing an attractive conversion

opportunity for the arbitrageurs. They will sell the calls, buy the stock, and

buy the puts. That will create demand for both the stock and the puts, bringing

them more into line with the appreciated calls. Naturally, other forces are at

work as well, such as the spread in valuations between the 70 strike and other

strikes or between the January expiration and other months. This is the reason

why an increase in a call premium does not necessarily indicate that that the

stock is expected to go up. By virtue of this type of arbitrage, an increase in

demand for puts with a given strike will cause both the puts and calls at that

strike to rise.

Many brokerage firms have employed option-stock arbitrage for years, and for good reason. It’s risk free and uses borrowed money. It is highly beneficial for the option markets as well, since it tends to keep the prices of put and call options in a set, predictable relationship with those of the underlying stock, and that is helpful for the markets overall.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 5: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques : Tag: Options : Define Partial Writing, Define Mixed Writing, Define Ratio Writing, Define Put Writing, Define Expiration Games, Define Option-Stock Arbitrage - Options Trading: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques

Options |