Options Trading: Major Advanced Call-Writing Techniques

Define Writing Calls on “Hot” Stocks, Define Tax Deferral Strategies, Define Covered Writing on Margin, Define Covered Writing against Securities Other Than Stock

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 5: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques ]

Options |

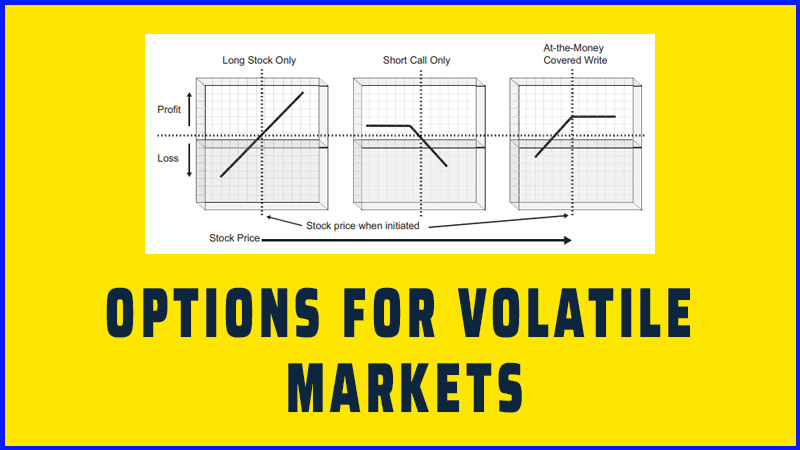

Flexibility is unquestionably one of the hallmarks of covered call writing. If you own stock and are not writing options, things are black or white you either hold your shares or you sell them.

ADVANCED CALL-WRITING TECHNIQUES

This chapter turns to more

sophisticated implementations of call writing, including the use of margin,

employing underlying securities other than stocks, and partial or ratio

writing.

Flexibility is unquestionably one of

the hallmarks of covered call writing. If you own stock and are not writing

options, things are black or white—you either hold your shares or you sell

them. Covered call writing expands your follow-up possibilities to include a

number of ways to hedge the stock, in terms of both the amount and the time

period. It also enables you to adjust the risk/reward parameters of your positions,

should either the stock price or the market conditions warrant it. This

flexibility expands dramatically over time, since you can write new options

once the initial ones expire or you can roll an existing position up or down or

out before expiration. In this manner, you can control how much or how little

of the total potential return you give up on the stock in exchange for a fixed

premium, and you can change this amount each time a new call is written. From

this perspective, a covered writer can actually use the options to drive the

returns on the underlying stock position.

The following are discussed in this

chapter:

- Participating in “hot” stocks, with lower risk and volatility

- Tax strategies

- Margined covered writes

- Writing against other securities

- Partial writing, mixed writing, and ratio writing

- Put writing

- Overvaluation

- Expiration

- Arbitrage

Writing Calls on "Hot" Stocks

If you like to “follow the action” and play hot (highly active) issues, you probably

have experienced some serious bumps and bruises in your day. Frequently, the

action involves a stock that has listed options, giving you an alternative way

to participate without taking as much risk, or by modifying the risk in price

or time.

The action in a given stock may be hot

for a variety of reasons—possible merger or acquisition, large potential deal

pending, earnings speculation, stock split, new product announcement, or rumors

of all kinds. If you’ve participated in these types of situations, you know

that some work out, but many do not. Most become roller-coaster rides

regardless of how they ultimately turn out. Generally, there is speculation

about a substantial move on the stock one way or the other. If an up move is

what you’re looking for, a covered write might be well worth considering. You

may not have as much ultimate upside potential as if you simply owned the

underlying stock, but you may be able to get a very attractive potential return

with much less risk, and you will have a greater likelihood of making at least

some profit than the stock buyer. Sometimes, when the speculation continues for

months with no big move, your comrades who bought the stock are suffering from

anxiety while you’re pulling in option premiums.

Consider the case of InterMune (ITMN).

The company developed and commercialized products for the treatment of serious

pulmonary and infectious diseases and cancer. The stock, which had been as high

as $52 in the preceding year, hit a low of around $16 in July 2002 before

moving up to $20 in the next few weeks. In early August, call volumes and

premiums began to rise precipitously. Rumors were circulating that the company

would announce the results before Labor Day of clinical trials on a potentially

lucrative new drug in testing. The company’s future could be so profoundly

affected by the results of the clinical trials that the stock might either

skyrocket or collapse, depending on whether they were favorable or unfavorable.

We looked at the stock when it was

trading between $20 and $21 and decided that the premiums in the September call

options made covered writes very attractive. We bought the stock at $20.80 and,

at the same time, were able to get the almost unheard of price of 4.00 for the

September 22.5 call (with one month to go before expiration!). That gave us a net

cost of $16.80 for the covered write, enabling us to profit even if the stock

dropped by 10 to 15 percent. For the next two weeks, the stock traded up to $22

and back to $18.

TABLE 5.1 Covered Write versus Stock Purchase

for ITMN

|

|

Stock

Purchase |

Covered Write (Selling Sep 22.5 Call) |

|

Cost |

$20.80 |

$20.80 |

|

Gain |

$1.86 |

$1.86 $1.86 (stock) + $1.75 (call) = $3.61

(Total) |

|

Raw % gain |

8.9% |

17.4% |

Then, on August 28, the announcement

came. It was good news, but not the blockbuster some had expected. By the end

of the day, the stock was at $22.66, and the Sep 22.5 call was priced at 2.25.

If the position was closed on those prices, the comparison of covered write to

stock purchase for the period would look like Table 5.1 (excluding

commissions).

Of course, anyone who actually

purchased the Sep 22.5 call at 4.00 lost nearly half of the investment if he or

she closed it on the day of the announcement.

Tax Deferral Strategies

Covered writing cannot eliminate a tax

responsibility, but it can help you postpone one. Say you have owned a stock

for many years and have a sizable capital gain on it. You wish to sell it, but

it is late in the year and you would like to postpone your capital gains

liability for another whole year. In the meantime, however, you are afraid the

stock may retreat from its current price. Writing an in-the-money call option

with an expiration in the next calendar year could provide you with the

downside protection you need until after year end. You don’t want to go very

far in the money with the call, however, because you do not want to risk having

an early assignment that could negate your plan entirely.

Bear in mind that tax rules prohibit

this practice until your stock position has exceeded the requirement to qualify

as long term. If your position is still short term, then writing an

in-the-money call could eliminate your existing holding period and restart the

clock when the call is closed. You can, however, write an out-of-the-money call

without incurring this restriction, although this may not provide you with as

much downside protection.

Covered Writing on Margin

Buying stocks on margin enables you to

increase your investment with money borrowed from your broker. This increase in

your portfolio gives you additional leverage, which means you earn more when

your investments gain but also lose more when they decline. The aim, of course,

is to earn more on the incremental investment than you spend on the interest

charged to borrow the money.

With low interest rates (say, 6

percent), you only need to identify covered writes that return more than 0.5

percent a month to come out ahead of a straightforward cash-only investment.

This sounds easy, but bear in mind that margined portfolios decline faster than

cash portfolios in a bear market. Their fall is exacerbated by the fact that

margin calls force you to liquidate parts of the portfolio as prices drop. When

many investors who have traded on margin are forced to do this, it helps

accelerate market declines.

Margin Rules for Covered Writes

Since stock is the primary investment

vehicle in covered writing, margining those stocks will give the covered writer

a similar leverage enhancement, but with a distinct advantage over a stock

owner: The option premium received from the covered write helps meet the margin

requirement. The general initial margin requirement on a covered write when the

option is out of the money is 50 percent of the stock price, less the option

premium received (net of commissions). Thus, the more premium you take in for a

margined covered write, the less money you have to put up to carry the stock,

and the greater your leverage.

Taken to the extreme, it would even be

possible to purchase a low-priced stock on margin and identify an in-the-money

call option that, when written, would supply enough premium to pay for the

entire 50 percent requirement to own the stock. But the brokerage industry does

not want clients purchasing stock completely with borrowed capital, so it

adopted an additional rule to limit the amount that can be borrowed on in-the-money

covered writes. This rule states: When a covered write is in the money, the

margin “release" (the amount a brokerage will loan you) is 50 percent

of the stock price or of the strike price, whichever is lower. The intent of

this rule is not to discourage margining in-the- money covered writes but to

prevent them from being initiated completely with borrowed money.

TABLE 5.2 Comparison of Cash and Margined

Covered Writes

|

|

Cash Covered Write |

Margined

Covered Write |

|

Net Investment |

$5125 |

$2375 |

|

Return* if Unchanged |

7.3% |

14.9% |

|

Return* if Exercised |

21.9% |

46.5% |

* Returns are calculated

using the net debit method. The maximum margin of 50 percent is used.

Even with this rule, you can still gain

quite a bit of leverage by margining in-the-money writes. Also, you can

frequently find out-of-the-money options in the more distant expiration months

(particularly among LEAPS) that provide enough premium to reduce the net outlay

for the covered write to a fraction of the stock’s cost. And these do not fall

under the purview of the above margin limit.

To illustrate the leverage that

margining gives a covered writer, Table

5.2 lists the potential returns of the following out-of-the-money covered

write, implemented both with and without margin:

Buy 500 ZZZ at $11.

Sell 5 Oct 12.5 calls at 0.75.

41 days till expiration.

Margin rate = 7 percent.

Commissions excluded.

Note that the covered write on 50

percent margin increases the potential returns from this position not just by a

factor of two, as you might expect, but by a slightly higher factor (46.5

percent versus 21.9 percent). The reason is that the investment required in the

margin scenario is not 50 percent of the cash investment, but only 46 percent:

The margin requirement is 50 percent of the cost of the shares ($5,500), or

$2,750, less the premium received ($375); that comes to $2,375, or 46.1 percent

of the cash investment of $5,125. As you sell calls with greater premiums

relative to the stock price, this effect becomes more pronounced. The more

option premium a covered writer receives, the greater the leverage when buying

the underlying stock on margin. Because of this, covered writers can obtain

even more leverage from margin purchases than stock buyers can.

An in-the-money example would show a

similar effect, although your margin requirement, before being reduced by the

call premium, may be slightly more than

50 percent of the stock price, because of the rule mentioned. If you were to

write the October call with a strike price of 10 instead of the 12.5 in the example

above, the maximum your broker would lend you would be half the strike price

rather than half the stock price—$2,500 instead of $2,750. Your net

requirement, after subtracting the premium, would therefore be $2,625 instead

of $2,375, or 51.2 percent of the cash investment. Writing in-the-money calls

on margin can thus provide both attractive downside protection and attractive

returns as a result of the leverage.

Advantages of a Margined Covered Write

The cash brought in from option

premiums on the covered calls you write not only reduces your margin balance

but also increases the equity in your account. This reduces your margin

interest and helps cushion the account against the necessity of liquidating to

meet a margin call should prices decline. Moreover, you can sometimes meet—or

at least partially meet—a margin call by writing covered call options in the

account rather than depositing additional cash.

Alternatively, the option premium you

receive can allow you to purchase even more stock. In fact, a covered writer

can sometimes acquire considerably more shares by using margin than a stock

buyer can. That’s because when you write calls in a margin account, the

premiums you receive increase your buying power by twice their value. So, by

using margin, you can acquire up to twice as much stock as you have capital

for, write options on that position, and use the cash from the options to buy

even more stock. You can then possibly write even more calls. The leverage can

be substantial.

Table 5.3 uses the following situation to illustrate how many more

shares margin allows a covered writer to purchase than a buyer of the same

stock.

In the margin scenario, the covered

writer’s capital requirement per 100 shares is half the cost of the stock (or

$550) less the option premium ($175). That means the net requirement is $375

per 100 shares, excluding commissions. With $5,500, the covered writer is thus

able to purchase 1,400

TABLE 5.3 Maximum Shares That Can Be Bought in

Cash versus Margin Accounts

|

Stock

Owner |

|

Covered

Writer |

||

|

Cash |

Margin |

|

Cash |

Margin |

|

500

Shares |

1,000

Shares |

|

500

Shares |

1,000

Shares |

Example:

ZZZ stock = $11/share.

Out-of-the-money call on ZZZ = 1.75.

Available funds = $5,500 round lots

only.

Commissions excluded.

The example in Table 5.3 illustrates the additional advantages that covered writers with fully margined positions have over straight stock owners. The effects are even more pronounced in this example because the stock is relatively low priced. These advantages, however, do not mean that you should necessarily leverage your self to the maximum or always use low-priced stocks. Using margin doesn’t have to entail taking a more aggressive stance. Margined purchases can be used for reasonably conservative strategies, such as helping to diversify a portfolio or enabling a smaller investor to buy more stable, higher-priced stocks.

Covered Writing against Securities Other Than Stock

The standard terms of an equity option

stipulate shares of the underlying stock as the deliverable item if assigned.

Thus far, only calls covered by the underlying shares themselves have been

discussed, but an equity option may be covered by an item other than shares of

the underlying stock, if that item is readily convertible into those shares.

That means you can write covered calls on warrants, convertible bonds,

preferred stocks, or even other options, subject to certain qualifications.

Writing Calls against Convertible Securities

The first qualification is that your

convertible security must convert into at least enough shares to cover your

short call options. If, for example, you have a bond that is convertible into

25 shares of common stock, then you would need four bonds to cover one call

option. The next qualification is that the convertible security cannot mature

or expire before the option’s expiration date. In addition, if it has a

specified conversion price into common shares—for example, a warrant for XYZ

shares at $15—the strike price of the call you are writing must be the same or

higher. These qualifications must be met for your brokerage to consider the

convertible valid as coverage for the short call. If you have any doubts about

whether a particular security qualifies, ask your broker.

Writing calls against warrants or

convertible bonds is not very common, since not many such issues are available.

Also, it is more challenging to find these situations, because these

instruments do not show up in most of the software used to find covered writes.

Bear in mind, however, that convertible securities have special characteristics

you need to consider when using them in your covered writing program. Some

convertible bonds, for example, are callable, meaning that they can be redeemed

before maturity on specified dates at specified prices. That could have

significant implications for pricing (the bond might not rise above the price

of its call provision) and could present a problem if your bond is called while

you still have a covered write associated with it. Also, securities like

convertible bonds and preferreds may have long lives or pay interest, causing

them to carry significant time value over their conversion value. In that case,

it will not be to your advantage to convert if you are assigned on your short

call, since you would give that time value up. You would be better served by

purchasing common shares to fulfill your assignment and then either holding the

convertible or selling it.

Writing Calls against Other Options—The "Call-on-Call" Covered Write

Covering calls with other options is

much more popular than writing against convertible bonds or preferred stocks.

Such positions are not called covered writes, however. In options lingo,

they’re referred to as bull calendar call spreads or diagonal spreads. We

prefer the term call-on-call covered write. However you label them, they work

the same way as covered writes on stocks.

Typically, you would look for an in-the-money

call to buy instead of stock. (Remember, the deeper in-the-money the call, the

less time premium—and you want to minimize time premium, since it represents a

cost to you in this strategy.) You need to select a call in an expiration month

that is farther out than the expiration of the call you want to sell and with a

strike price that is the same or lower. Otherwise, your brokerage firm will

consider your short position uncovered.

The primary advantage of using an

option as your underlying security rather than buying the stock is that you put

up a lot less money. If you want to write a covered call on IBM when it is

selling at more than $80 a share, you have to pay more than $8,000 for one

round lot of the stock. Even on margin, you would need to put up $4,000 (and

pay interest). If, instead, you buy a five- or six-month call option on IBM

that is around 15 points in the money, your investment would probably be well

under $2,000.

TABLE 5.4 Covered Write against Stock and

against Another Option

|

Stock Owner |

Covered

Write on Stock (Cash) |

Covered

Write on Stock (Margin) |

Call-on-Call

Covered Write

|

|

Net

Investment |

$7,640 |

$3,640 |

$1,350

|

|

Return if

Unchanged |

4.7% |

8.7% |

20.7%*

|

Note: Returns calculated

using the net debit method.

* Assumes that the Jan.

65 call will be worth 18.10 at October’s expiration.

Your capital requirement in this case

is governed by spread rules, which say that you must put up the difference

between the option you purchase and the one you sell—that is, the net debit of

the two positions. Essentially, that means that your long option is not

marginable and must be paid for in full. To invest in spreads, you will need to

be approved for the strategy by your brokerage firm and will be subject to a

minimum equity requirement in your account (over and above the cost of the

spread), probably equal to $10,000 or more.

Table 5.4 shows your potential returns from writing a call against a

cash (non-margined) stock position, a margined stock position, and another

option, given the following situation:

Buy 100LMN at $81.80.

or

Buy 1 LMN Jan 65 call at 18.90 (149

days to expiration).

Sell 1 LMN Oct 80 call at 5.40 (58 days

to expiration).

Margin rate = 7 percent, and margin

requirement = 50 percent of strike price ($4,000).

Assume no dividend in this time period.

Commissions are excluded.

If you choose to write against the

January call, when the October expiration comes around (or anytime before, for

that matter), you can roll the October call or close the whole position, just

as you could if you were writing against shares. You could write calls expiring

in October, November, December, or even January while continuing to use the

January call to cover them (as long as you are writing a 65 or higher strike

price). The amount of time premium you are paying for the January call with the

stock at its current price is only 2.1 ($210). This is the cost (if held all

the way to January) of using a call option instead of buying the stock at this

price. Just for comparison, the margin interest on $4,180, the maximum margin

release in this situation, at 7 percent for 149 days would be $119.44.

Additional considerations apply when

doing call-on-call covered writing. If you are assigned on your short position,

you generally will want to sell your long option, as opposed to exercising it,

if it has any time value remaining. To prevent being forced to take either

action, investors who write calls against other calls are usually more

attentive to the short side of their position, with an eye toward rolling or

closing rather than waiting until the last minute to see if they will be

assigned. And remember that when you cover with a call option instead of a

stock, you don’t receive any cash dividends, should there be any, or have any

voting rights.

It might seem riskier to write a call

against an option than against a stock. Actually, the reverse can be true.

Granted, if you take a much larger position because it costs you less to put

on, your overall risk in absolute dollars would indeed be greater. But if you

buy the same position and just put less money into it, your total downside risk

on that position is lower, for the same potential dollar profit. A call-on-call

writer has less total capital at risk than the holder of an equivalent number

of shares. If LMN in the example dropped to $50, the stock owner would be down

$3,180 on 100 shares, whereas the call-on-call writer would be out only the

initial investment of $1,350.

When you use an option as a covering

security, the time value in the long call position is an added cost, because it

will decay to zero by expiration. But you can still expect to lose less money

than the covered writer with stock if the stock declines in the near term. A

long position in the stock declines dollar for dollar with the share price, but

the long in-the-money call position loses less than a dollar for every dollar

drop in the stock. That’s because the option picks up more time value as its

strike price gets closer to the current price of the stock.

To see how this works, assume that LMN

in the example above suddenly dropped to $70. The covered writer who owns the

stock (whether in a cash or margin account) would have an unrealized loss of

$11.80 per share. The call-on-call writer would lose less. An approximate

theoretical value for the Jan 65 call a month into the period with LMN at $70

would be around 10, which puts the unrealized loss in the call at only 8.90.

Although the option would lose as much as the stock if the share price was $70

at expiration, a call-on-call writer who closes out the position a month from

now would lose less than a writer against the stock.

Covered Writing on LEAPS

As explained in Chapter 1, long-term

equity anticipation securities (LEAPS) are equity options that are issued for

long periods (one, two, or three years) and that always expire in January.

(LEAPS on ETFs and on indices expire in December.) For the most part, LEAPS are

available on large-cap stocks with actively traded regular options. Fewer

strike prices are available on LEAPS than on short-term options, and their

trading volume is usually lighter.

Since LEAPS are identical to regular

options except for their longer expirations, they can be used interchangeably

or in conjunction with other options to create various strategies. You can

write a LEAPS option against a stock as a long-term covered write, or you can

use the LEAPS option as a surrogate for owning the stock (as in call-on-call

writing) and write a covered call against it.

Writing a LEAPS option against stock

brings in a substantial amount of option premium, which in turn lowers your

investment and provides leverage. If you write a one-year LEAPS option against

a stock, you have the whole year to compound your returns from that premium.

What’s more important, the premium you bring in can offset a substantial

portion of your initial outlay for the stock. The premium received from writing

an at- or slightly out-of- the-money LEAPS option against a relatively

low-priced stock, for example, could be sufficient to cover nearly half the

cost of purchasing the underlying stock on margin.

The more popular use for a LEAPS option

in a covered write is as a substitute for the underlying stock. This works

exactly the same way as writing on any other call option. The strategy is thus

an implementation of call-on-call writing with a longer-term option as the

covering position. Since you pay more in time value for a LEAPS option, what is

its advantage over a shorter-term call? For one thing, the time value in the

LEAPS option declines more slowly. For another, if you hold the LEAPS option

for more than one year, your gains, if any, could potentially be taxed at

long-term rates. In addition, since LEAPS options tend to be more sensitive to

interest rates and volatility, at a time when both of these factors are low, a

LEAPS call might represent an attractive long-term purchase.

You need to be aware, however, of

several differences that exist between LEAPS and regular equity options. The

decay in their time value, for instance, exhibits slightly different

characteristics, such as accelerating when they have only six months to

expiration. Also, an at-the-money LEAPS option might not gain much value even

for a sharp upward move in its underlying stock. Consequently, it is

conceivable that the gain on a LEAPS option would be less than the loss on a

short-term option you write against it, thereby losing you money for the

period, even though your stock went up.

For more information on LEAPS, see

Lawrence McMillan’s Options as a Strategic Investment and the CBOE web site

(www.cboe.com), which has information on LEAPS, including symbols and strategy

discussions.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 5: Advanced Call-Writing Techniques : Tag: Options : Define Writing Calls on “Hot” Stocks, Define Tax Deferral Strategies, Define Covered Writing on Margin, Define Covered Writing against Securities Other Than Stock - Options Trading: Major Advanced Call-Writing Techniques

Options |