Options Trading: Calls to Write, Risks, Basic Tax Rules for Options

Stock, Investors, Tax Rules, Strategy, Investment

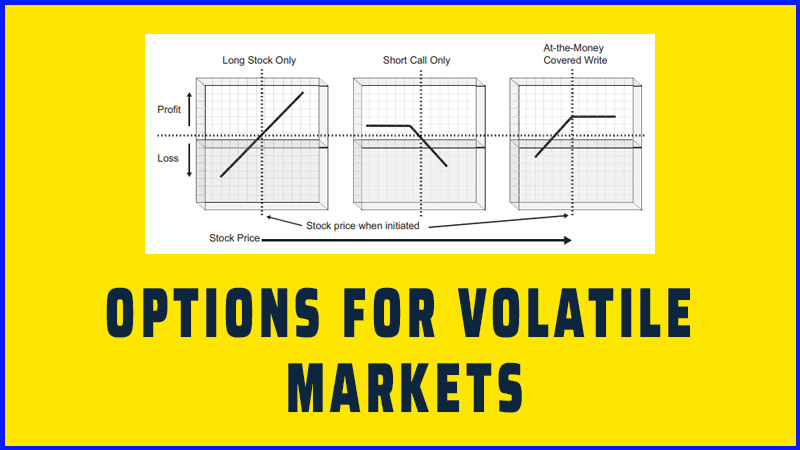

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 4: Implementing Covered Call Writing ]

Options |

Depending on the stock, it’s possible that you could have anywhere from 10 to more than 100 call options to choose from at any one time.

Selecting Calls to Write

Depending on the stock, it’s possible

that you could have anywhere from 10 to more than 100 call options to choose

from at any one time. However, the pool decreases quickly when you limit the

candidates to those that match your game plan. If you like to write

at-the-money calls with one or two months to expiration, you will zero in on

these. If you are writing for incremental return on a stock you already own,

you will probably start with the highest strike price available and work down

from this or move out in time until you find a call with sufficient premium.

Which Strike Price?

The strike price decision essentially

grows out of your risk posture and will generally boil down to a choice between

one or two strikes. The vast majority of covered calls that are written are for

the strike closest to the current share price, whether in- or out-of-the-money.

Table 4.5 illustrates how different

prices can correspond to different strategies, using a September-expiration

covered call written on Dell, Inc. (DELL), when the stock was trading at

$26.25.

Bear in mind that while the situation

illustrated in the table is typical of the trade-offs between in-the-money and

out-of-the-money calls, the scenario is dynamic. A $1 move up or down in share

price could easily change which call you write or even cause you to reject

writing on that stock at all. Many times you will like a stock but not find a

call that suits you. The following month, or the following week, the same stock

may offer a much more attractive write. Much of this variation in

attractiveness has to do with where the stock is trading relative to the strike

prices of its options. It is most likely to happen with stocks priced between

$30 and $50, whose options have strike prices in $5 increments. Say you prefer

covered writes where the underlying stock is trading one or two dollars below

the strike price. If a stock you like is trading at $38, for example, you most

likely would be comfortable with the amount of premium that the 40 strike

offers, and you would still have some upside potential in the stock. The 35 call

would probably be too far in the money to offer a high enough return and would

offer no upside in the stock at all, while

TABLE 4.5 Strike

Price Selection

|

Strike Price |

Option

Price |

Strategy |

|

Sep 22.5 call |

4.40 |

This is the ultraconservative strike.

You earn only 0.65 of time premium before commission—a 2.5 percent gain for

39 days. It probably won’t pay for a small account that holds only a few

hundred shares. But for someone with a larger account, paying very low

commissions, who wants plenty of downside protection (in this case, nearly 17

percent), this could be the preferable strike. |

|

Sep 25 call |

2.50 |

This strike is still relatively

conservative. The option pays 1.25 of time value before commission—a 4.8

percent return—and still provides almost 10 percent downside protection. |

|

Sep 27.5 call |

1.10 |

This is the modest-risk covered write

and the one most writers would probably select at this stock price. It offers

almost as much static gain as the 25 strike (4.1 percent), and although the

downside protection drops to the same 4.1 percent, the upside potential (RIE)

jumps to nearly 9 percent, before commission, for the 39 days. |

|

Sep 30 call |

0.30 |

This is the aggressive covered write,

with only a marginal (1.1 percent) static return. It is almost like simply

owning the stock, because there is so little downside protection. Like the

ultraconservative strike, it wouldn’t really pay at low volume, since you are

only getting $30 per contract, less commission. Even for large accounts or

investors writing for incremental return, such a write is of questionable

benefit.

|

the 45 strike might not provide enough

premium. But if the stock is trading at $35.50, none of the available strikes

may suit you, and you may decide to write on a different stock for the present.

Next month, the first stock may be exactly where you want it. How you choose

between in-the-money and out-of-the-money calls is up to you. There are good

rationales for both at different times, and even for using both at the same

time on different stocks. It all comes down to how much of a stock’s upside

potential for the period you are willing to trade away for more return. Be

advised, however, that if you find yourself always selling the in-the-money

calls, you may not be allowing yourself enough upside potential in the long run

to offset the risks on the downside. While downside protection is often

advantageous, if you believe that stocks do in fact have a long-term upward

bias, you should profit from that growth if possible.

Which Expiration Month?

Time premium is the component of an

option’s total premium that diminishes over time, and as a call writer, this

decay is what makes you money. Chapter 2 explained that time premium decays

faster as an option approaches its expiration. That means that all other things

being equal, to take the most advantage of the dissipation in time value of

call options, writers are best served by writing the near-month option whenever

possible. That is why so much of this book uses examples that are one to two

months in duration. You can frequently find very attractive covered writes even

in the last one to three weeks before an expiration. Say you are assigned on a

position and have money to reinvest but can’t find anything in the next

expiration month you really like. A week later, with only three weeks to go

before that next expiration, you might be surprised at some of the

opportunities that surface for either that month or the next one out.

Although some people find it difficult

to take what might be considered such a short-term perspective, it has some key

advantages:

- Over time, you take in more time premium per day in your positions, thereby enhancing your overall returns.

- You have much more flexibility to roll your option positions should you decide to. (By writing in the nearest month, you have the most other months to roll out to and the greatest likelihood of rolling for a credit.)

- You have more flexibility to adjust to market conditions or seize on opportunities that arise (because you’re tying your money up for less time).

- You don’t ride positions too long because you’re forced to re-evaluate your positions every month.

If you have idle funds or extra buying

power in your account, there is nothing wrong in putting on a covered write

just a week or even a few days before option expiration. Some people, however,

sell out-of-the-money calls on the last trading day before they expire without

buying or owning the underlying stock, reasoning that with expiration so near,

they needn’t incur the expense and risk of owning the shares. This is a temptation

you should resist. True, calls on volatile stocks can carry premiums of 0.10,

0.20, or more with only a few hours of trading left and the stock selling below

the strike price. But unless you buy the underlying stock, these are considered

naked calls, even if you write them only a day before they expire. This would

represent an account violation if you aren’t approved for naked call writing.

In addition, you won’t be happy if big news about the company is announced

after the close that day, causing you to be assigned on stock you don’t own,

and which subsequently opens much higher on Monday morning.

The only real consequence of a

short-term approach is that you will pay more commissions, since you are

writing more often. How much of an impact this will have on your returns

depends on the fee structure of the brokerage you use.

Risks

- Despite the fact that call writing reduces risk, it still entails risk.

- Market risk. Covered writers need to remember that they are stockholders and are subject to the market risk of their stock positions—that is, the risk posed by the fact that their shares will fluctuate in price and that this movement is beyond their control. The sale of call options may offset part, but never all, of that risk.

- After you buy a stock at $37.5 and sell a 40 call, the share price is as likely to drop to $35 as it is to rise above $40 by expiration. This is a fact of life for stock investors and does not change when you write calls. The calls do smooth the net effect of these fluctuations, but they do not affect the chances of them occurring.

- Trading/execution risk. Trading risk relates to the fact that prices can move while you are trying to execute the two parts of your covered write. Placing your stock and option orders as close together in time as possible will mitigate this risk, but if you intentionally wait between orders, hoping for a better price, you increase the danger of getting a worse one.

- Trading halts. Trading on listed options is always halted when trading on the underlying stock is halted. This might happen after an announcement that significantly affects the share price, to allow the news to be digested and orders to be balanced. Option trading also can be halted for external reasons, such as a power failure on the exchange floor or other such calamities. Usually, these interruptions are brief, but there is no way to predict their occurrence or duration.

- When trading is halted on a listed option, holders still have the right to exercise, and writers must fulfill their contracts. You cannot, however, go into the marketplace and close out your position. A trading halt is typically a temporary situation and not a major problem for covered call writers. Option holders, on the other hand, can be forced to exercise if they are unable to sell their options in the open market. Consider the following, somewhat extreme, example: You own XYZ stock and have written the March 55 call. It is Thursday before March expiration and a hostile takeover offer has been made for XYZ at $60. Trading in the stock is halted at $53 and does not reopen on Friday. Heavy speculation will occur on the upside, but until the stock trades, holders of the XYZ March 55 call will not know whether or not to exercise. If they feel the stock will open on Monday above $55, the holders will want to own it and will have to exercise. Otherwise, the call will expire worthless. On the other hand, they may feel the stock will settle back first, giving them time to buy it below $55 on Monday or whenever trading reopens. Some holders may thus choose to exercise while others may not. That means you may be assigned or you may not. Either way, though, the situation has not hurt you, except that it prevented you from closing your position before expiration.

- An underlying stock can also be delisted, or it may no longer meet the minimum criteria for having listed options—it may fall below $5, for instance. In this event, no new options would be issued, and while existing ones may continue to trade, there may be greatly reduced liquidity. Such options can, however, still be exercised.

Basic Tax Rules for Options

If you do your covered writing in a

qualified retirement account, such as a self-directed Individual Retirement

Account (IRA), you don’t have to worry about any of the tax consequences (which

makes it an appealing place to use the strategy). But if you use a regular

taxable brokerage account, you’ll have the extra burden at tax time of having

to account for all of your stock and option transactions in the prior year. In

addition, you’ll need to be aware of some special tax rules that apply to

covered writing. This section looks at those rules. Bear in mind, though, that

tax rules can change. Also, you may be affected by other more broadly directed

tax rules beyond those mentioned here. We advise that you consult the latest

IRS documentation or your tax adviser before filing your taxes. And if you’re

considering a strategy specifically designed to defer taxes, consult a tax

adviser before implementing it.

- Capital gains and losses from options are subject to taxes, just as those from stock are, and the holding period is the same. You may consider option premiums as income, but the IRS treats them as capital assets. Currently, you have to hold an asset for at least one year in order for a gain on its sale to qualify for the lower tax rate charged on long-term capital gains. Since the longest duration for conventional listed options is nine months, their premiums will always be subject to the short-term rates. The only way an option investment by itself would ever be long-term is if you purchased or sold a long-term equity anticipation securities option and held it for more than one year.

- Options used in covered writes are taxed as separate securities from the underlying stock unless they are exercised. If you close your covered write position before the expiration date or the option expires worthless, the option is taxed as a separate security. This means that you are subject to capital gains tax on the difference between the premium you received for writing the call (net of commissions) and your cost basis. If the option expires worthless, your cost basis is zero, so you pay tax on the entire sales proceeds; if you close the position, your basis is the price you paid to buy the offsetting option, so your taxable gain equals the net premium you earned minus the premium you paid. (An exception to this is that any loss with respect to a qualified covered call, as defined below, is treated as a long-term capital loss if at the time the loss is realized, a gain on the sale or exchange of the underlying stock would be treated as long term.)

- If the option you wrote is assigned, then the option becomes part of the stock transaction for tax purposes. For a stock held less than a year when you’re assigned, taxing the option and stock together is no different from taxing them separately, since all short term gains and losses are combined when you file, anyway. But if the stock is already a long-term holding, it could make your call long term as well. (Additional rules governing this situation are explained in Table 4.6.)

- Anti-straddle rule. The anti-straddle rule is designed to prevent the mismatching of gain and loss for tax purposes. A straddle, in IRS terms, involves “offsetting positions” where one creates “substantial diminution of risk of loss” on the other. When offsetting positions exist, the rule suspends or terminates the holding period while the offset exists and prohibits a loss to be taken on one side if there is an unrecognized gain on the other. Writing in-the-money covered calls creates an offsetting position that is subject to this rule. The rule only applies, however, to options that are in the money when written and when the stock is not yet a long-term holding. In applying the rule, the IRS makes a distinction between qualified and nonqualified calls, corresponding basically to those that are only slightly in the money and those that are substantially in the money.

TABLE 4.6 Options Taxed as Separate Securities

|

Example: Buy 100 GHI at $32 Sell 1 GHI Feb 35 call at 1.75 (after commission) |

|

|

Situation |

Tax

Consequence |

|

The option expires—worthless. |

Short-term taxable gain of $175 - 0 =

$175 |

|

You close the call at a profit,

paying $45 for the offsetting option after commission |

Short-term taxable gain of $175 - 0 =

$130

|

|

You close the call at a loss, paying

$225 for the offsetting option after commission |

Short-term taxable loss of $175 - 225

= — $50 |

|

You are assigned. |

Your taxable gain of$175 from the

option is added to the gain of $300 on the stock for a total gain of $475 |

If, when a covered call is written, the

option is nonqualified and the stock is not yet long term, the holding period

of the stock is eliminated entirely while the call is in place; the

holding-period clock must therefore start over at zero when the call is closed.

If a covered call option is qualified, then the holding period of the stock is

suspended while the call is in place; in other words, once the call is closed,

the clock can pick up where it left off.

With these rules, the IRS is preventing

investors from executing essentially no-risk tax strategies using call options

but still allowing tax-deferral strategies when the call writer’s positions are

at risk. Thus, you can write out-of-the-money covered calls to defer taxable

events on your portfolio, either to benefit from long-term capital gains rates

or to push a tax liability into the next tax year.

- Fulfilling an assignment with newly purchased stock. If you are assigned on a stock on which you have a substantial unrealized gain, you can elect to avoid the large tax liability by purchasing new shares of the same stock in the market to deliver against the assignment. You need to make sure your broker is aware that you are doing this so that the trade confirmation can indicate the new shares as the ones being delivered against the assignment. Naturally, additional commissions apply, and there is a tax consequence on the new shares to consider as well.

Say you write an August 45 call on 100

shares of General Motors stock that you have held for 20 years, at a very low

cost basis, and are later assigned. You inform your broker that you want to buy

100 shares of GM at the current market price, which happens to be $46.30, and

deliver those shares against your assignment instead of your 20-year holding.

You further instruct your broker to mark the confirmation for the sale of 100

shares via assignment with the remark “versus purchase of 100 shares at $46.30”

and add the date. In this way, the 100 shares you buy in the market will be

paired up with the sale of 100 shares via assignment for tax purposes, giving

you a cost basis for the transaction of$46.30, and you still own your original

shares, with the 20-year holding period intact.

- “Wash sale” rule. The wash sale rule says that you

may not take a tax loss on the sale of a security if within 30 days before or

after that transaction, you purchase either the same or substantially identical

security. Thus, if you have a loss on a stock and sell (or are assigned on)

that position and you buy the stock again (whether you write calls on it or

not) within 30 days, you will have to wait until you sell the new shares to

take the tax loss on the earlier shares. Note that for the purposes of this

rule, a deep in-the-money call that you buy after selling shares in the

underlying stock could be considered a substantially identical security.

- “Constructive sale” rule.

This rule addresses the situation in which a security has appreciated and the

investor seeks to avoid the tax on the gain by selling a different security

instead. If the second security eliminates the risk of loss and the upside gain

potential of the first, then the investor is deemed to have entered into a

“constructive sale.” When this occurs, the investor must realize the gain that

would have existed if the appreciated security were sold at its fair market

value. As in the anti-straddle rule, writing deep in-the-money calls can

potentially trigger this rule, although calls that are out of the money or

those that are qualified do not.

Summing Up Implementation

One of the key attractions to call

writing is the flexibility to implement the strategy in different ways, thereby

tailoring it to individual situations. The strategy thus provides very

attractive benefits in lowering risk and volatility in equity portfolios, but

also requires more work and attention than simply holding stocks, and will

carry different emotional characteristics than simply owning stocks. The

strategy, therefore, is not particularly appropriate for investors or managers

who are not able to perform the additional tasks associated with implementing

and monitoring the strategy on an ongoing basis. Indeed, the practicalities of

monitoring dozens or perhaps hundreds of individual client portfolios is a

deterrent to the widespread use of call writing by many portfolio managers.

That said, call writing is not

difficult to implement in an individual account, nor does it add additional

risk, even if not monitored closely. The worst case for those who initiate call

writes and fail to monitor them is the possibility of having the stock called

away when you might prefer to hold on to it.

Follow-up action may provide a way to even improve upon the basic strategy or tailor it to specific needs, opportunities, or market conditions, making call writing an ongoing investment management program that can provide benefit in almost any environment.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 4: Implementing Covered Call Writing : Tag: Options : Stock, Investors, Tax Rules, Strategy, Investment - Options Trading: Calls to Write, Risks, Basic Tax Rules for Options

Options |