Options Trading: Implementing Covered Call Writing

Summary on rolling, Define rolling options, Define Follow-Up Actions, Define Behavioral Issues, Define Differing Approaches

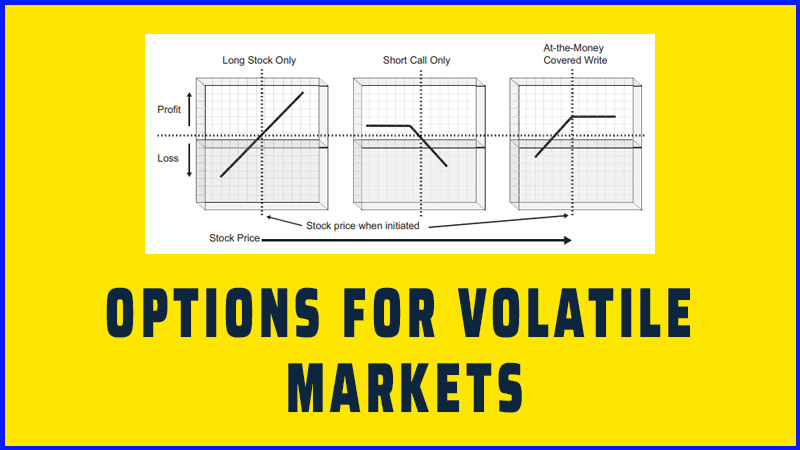

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 4: Implementing Covered Call Writing ]

Options |

Covered call writing can be simple or complex, depending on your approach. Through the selection of the underlying stock to buy and the particular call option to write, the strategy can be tailored to a multitude of different risk levels and market conditions, as well as a variety of goals and approaches.

IMPLEMENTING COVERED CALL WRITING

Covered call writing can be simple or

complex, depending on your approach. Through the selection of the underlying

stock to buy and the particular call option to write, the strategy can be

tailored to a multitude of different risk levels and market conditions, as well

as a variety of goals and approaches. This chapter discusses the various uses

covered writing can be put to and the ways it can be modified to suit various

circumstances.

Follow-Up Actions

In the process of creating a covered

write, you will discover that it alters not just the risk/reward parameters of

your stock investment but the way you invest as well—your selection process,

your expectations, and your follow-up activities. The change in your thinking

and the implementation of follow up activities are what will turn a position in

your account into an ongoing investment strategy.

You may feel that it is not necessary

to monitor a covered write as closely as a stock position by itself, and that

is generally true. However, you should remember that the option has a limited

life and that you will need to take follow-up action at some point. Follow-up

actions can be taken at any time, even before the option expires, and may be

warranted if the stock moves sharply or if you have reason to believe it may do

so. Such follow-up actions are discussed later, but first consider the simple

case—the one where you do nothing until expiration.

The Simple Case: Doing Nothing until Expiration

Once you put on a covered write, you

need not take any further action, even at expiration. You can do absolutely

nothing—you don’t even need to be around. You can be in Tahiti on expiration

day if you want. There is nothing about a covered write that adds any more risk

than if you simply owned the stock.

At expiration, the option will do one

of two things: expire worthless or be exercised. If the option is exercised,

your stock will be called away, and you will have an automatic sale of the

underlying shares just as if you had put in a sell order. On the other hand, if

the call expires worthless, it disappears from your account by the following

Monday and you revert to your status as a simple stockholder. Exercise is now

automatic for all options that are at least one cent in the money (ITM) at

expiration. If the stock closes anywhere below the strike price of the option,

you can count on not being assigned. (Note, however, that while extremely rare,

there could be extenuating circumstances under which a holder might decide to

exercise a call that has no value on the close before expiration. Such a

circumstance could include a surprise announcement immediately after the close

on Friday that would make the stock likely to trade higher in after-hours

trading or on Monday.)

While being assigned provides the

maximum gain for the period, having calls expire worthless is also gratifying,

because you know you have done better for the period than someone who simply

owned the stock. What’s more, you are now free to write another option and take

in still more premium.

Closing Part or All of the Position

Once you begin writing covered calls on

a regular basis, you will discover numerous reasons why you might want to close

or modify a position before expiration. News affecting the stock may become

public, or you may need the money for something. Or you may simply wake up one

morning and ask yourself, “What was I thinking?”

The reason is irrelevant. The ability to adjust your position on the fly

is one of the great benefits of covered writing. One alternative is to close

out part or all of your position. You can do this whenever you want, provided

you have not already received an assignment notice on any of your calls. Of

course, in closing, you will incur transaction costs and may realize a loss on

one or both sides of the transaction, so you do not want to be day-trading

covered call writes. But when the necessity arises, the ability to close is

there.

Say that in September you buy ABC stock

at $32 and sell a January 35 call for three points, for a net investment of $29

a share (not including transaction costs). Then in October, the stock falls to

$27. You believe it could drop further and would like to prevent additional

risk, but your call option still has nearly three months until expiration and

is trading at 1.5. Closing would leave you with net proceeds of $25.50 a share

($27 for selling the stock, minus $1.50 for buying back the offsetting call).

That gives you a loss of $3.50 per share (the initial net investment of $29

minus $25.50), plus transaction costs, on the covered write (compared with a $5

per share loss had you simply owned the stock and not written a call). If you

believe that the stock could go to $20 or below over the next three months, then

holding on to a short call that will only give you $1.50 more profit during

that time may not make sense. Closing the whole position in that scenario is a

justifiable action.

The important point to remember is that

your net investment incorporates both the stock and the call option, but the

stock contributes essentially all the downside risk. Therefore, it behooves you

to assess where you believe the stock may go even more than where the option

may go and not to be shy about closing the option or both sides if necessary.

Another tactic many people fail to

appreciate is closing only part of the position. If you have 800 shares of a

stock and write eight calls, you can always compromise by closing only four of

the options. For some reason, people get stuck on the idea that it’s all or

none and don’t consider lightening their position as opposed to closing it

entirely. The same holds true for putting on the position in the first place.

Not sure if you should sell a covered call on all 800 shares? Why not sell only

four, or sell four at a conservative strike price and four at a higher one?

One caution on closing covered writes:

You’d be very ill-advised to close the stock and keep the short call position

open, even if you are trying to avoid taking a loss on the option. Whether or

not you are approved for naked options, it is an unwise practice to close a

covered write by selling the stock first and holding an uncovered short

position in the call. You can, however, buy another call to create a spread

with the one that is short, thus freeing you to sell the underlying stock

without creating a naked short call. The call you purchase could be at a higher

strike call in the same month to create a credit spread or a longer dated call

at the same or lower strike to create a calendar spread. The purchase of a long

dated call instead of stock in the first place is an advanced call writing

strategy, which is discussed in Chapter 5.

Rolling Options

While closing the entire covered write

is sometimes justified, more often, you will decide to hold the stock and close

only the option or roll your call position. Rolling refers to the process of

closing out the short call position and opening a new one in its place. Think

of it as simply substituting different calls for the ones you are currently

short. This allows you to adjust the risk/reward potential of your position

while leaving the stock holding intact.

The act of rolling involves both a

purchase (to close your original short position) and a sale (to establish a new

short position). You will generally want to execute the two transactions as

closely together as possible to minimize the risk of having the stock move

between the time you execute one side and the time you execute the other. Even

though the stock could move in a direction favorable to the second half of your

transaction after you’ve completed the first half (giving you a better price),

why take that risk? Your objective is to have a covered write, not to day-trade

options. Therefore, rolling is normally accomplished either in two nearly

simultaneous transactions or as a single transaction executed as a “spread” order.

Having said that, there may be

occasions when you wish to close your short call position and not reopen a new

one at the same time. You could, for example, write a call option against stock

and subsequently learn that some positive things may be brewing. Rather than

cap your upside with a covered call, you may decide to close the short call

position and wait a week or two to see if your stock rises or any news comes

out. Trading in and out on the short call of a covered write is not recommended

as an ongoing practice, but changing your mind for valid reasons now and then

is completely up to you.

Rolling is a valuable technique,

allowing you to manage the risk and reward of your covered writes after you

have initiated them. However, it has a price. It will add transaction costs and

can sometimes require additional funds to implement (if the call you repurchase

is more expensive than the one you roll to). Furthermore, it will not always

end up being a better course of action than having done nothing. As with

changing course on any investment decision, your success is ultimately a

product of the accuracy of your judgments.

Below is a discussion of how and when

it might be appropriate to roll options up, down, or out. The following example

will be used throughout:

Buy 100 DEF at $28.

Sell 1 Feb 30 call at 2.

Days to expiration = 60.

Rolling Up

Suppose you buy DEF at $28 and write

the DEF February 30 call at 2 in December. Suppose further that it is now

January, and DEF is trading at$32 and looking strong.

TABLE 4.1 Pricing Scenarios on DEF Calls

|

Original Scenario (two months to expiration) |

New Scenario (one month to expiration) |

|

DEF

= $28 |

DEF

= $32 |

|

DEF

Feb 35 Call = 0.5 |

DEF

Feb 35 Call = 1 |

|

DEF

Feb 30 Call = 2 |

DEF

Feb 30 Call = 3 |

|

DEF

Feb 25 Call = 4.25 |

DEF

Feb 25 Call = 7.3 |

The covered write is working well, and

you have an unrealized gain at this point: Your call is worth three points,

netting you a potential $29 per share before transaction costs should you close

both positions now. If the stock remains above $30 at February’s expiration,

you will achieve your maximum gain from the initial covered write. You can

certainly opt to do nothing and wait for that to happen.

But you may feel that the stock could

move even higher over the next month. If you are that confident, you can adjust

your position to allow you more upside potential by rolling up to the February

35 calls. The following pricing scenario exists (Table 4.1).

Rolling up to the Feb 35 call would

involve buying the Feb 30 call to close your current position and selling the

Feb 35 call to establish a new covered write. Since you are paying three points

and receiving one, you are paying out two points net, or $200 per contract.

This payment is your net debit for the transaction and represents an addition

to the initial cost of the investment. This cost happens to cancel out the two

points earned on the original option write, so in a sense, it is giving back

the original premium received. But your stock has gone up accordingly, so you

are still ahead of the game. Depending on how much time remains before

expiration and how high the stock has moved, your net cost to roll up could be

more or less than what you originally received. Even if you realize a loss in

the option you are buying back, you should always have a greater gain (albeit

unrealized) in the underlying stock than your loss in the option.

Why do this? The logic would be that

you are increasing your upside potential, although you are also adding to your

original investment and thereby increasing your risk at the same time. Your

original position gained a maximum of four points at expiration if exercised

(30 for your stock plus two from the option minus your net initial investment

on the stock of 28). Your new position now gains a maximum of seven points if

exercised (35 for the stock plus zero from options minus your investment of

28). Your breakeven point is higher now, and your time period is unchanged.

TABLE 4.2 Rolling Up

|

|

Original

Scenario |

New

Scenario

|

|

Premium received (in points) |

2 |

2-3 + 1 =

0

|

|

Maximum potential stock gain (strike

price less initial stock price) |

30-28 = 2 |

35-28 = 7

|

|

Total potential gain from stock and

options |

4 |

7 |

|

Breakeven stock price (initial stock

price less premium earned) |

$26 |

$28

|

|

Time period |

Feb

expiration |

Feb

expiration |

The comparison of risk/reward looks

like what is shown in Table 4.2.

One way to decide whether this is worth

doing is to look at your incremental investment and incremental gain. Here, you

are putting in an extra $200 for an increase in your maximum potential gain of

$300. That would be more than 100 percent on your incremental investment if

realized, although when you figure in your transaction costs, it will be

somewhat less. But what is the probability that the stock will actually be over

$35 by February’s expiration? That’s for you to decide.

A little rough arithmetic tells you

that the original covered write makes four points if the stock is above $30,

while the new scenario makes four points if the stock is above $32 at

expiration. Therefore, if the share price is below $32, you will have been

better off not rolling, and if it is higher than $32, your roll will have been

beneficial. (If you do this kind of quick math, you might want to toss in an

extra half point for the transaction costs.)

This example used strike prices with

five-point increments, but there are lots of situations now that offer

2.5-point increments or even one-point increments between strikes. Such

situations offer that many more possibilities for rolling and are advantageous

to the call writer.

Rolling Up and Out

Many people like the idea of rolling up

for more potential gain on a covered write position but not the part about

putting in additional capital. That’s where rolling up and out comes in. You

roll up in stroke price but also move out to a more distant expiration month.

TABLE 4.3 Rolling Up and Out

|

|

Original

Scenario |

New

Scenario

|

|

Premium received (points) |

2 |

2-3 + 3.5

= 2.5

|

|

Maximum potential stock gain (strike

price less initial stock price) |

30-28 = 2 |

35-28 = 7

|

|

Total potential gain from stock and

options |

4 |

9.5 |

|

Breakeven stock price (initial stock

price less premium earned) |

$26 |

$25.5

|

|

Time period |

Feb

expiration |

Apr

expiration |

By moving out in time, it is frequently

possible to get more premium from your new write than it will cost to buy back

your existing one. In other words, you will be rolling for a net credit rather

than for a net debit.

Suppose you wish to roll up to the 35 strike

price on your DEF calls, but you want more premium than is available in the Feb

35 call. Try March. Say the March 35 call is 2.25. That’s a reasonable roll,

but it will still cost you 0.75 points, or $75, per contract to do it. Assume

there is an April 35 call at 3.5. This roll would give you a credit of 0.50, or

$50, per contract. The April 35 call would extend your covered write two more

months, but in the process you gave yourself more upside on the stock and it

didn’t cost you a nickel (Table 4.3).

Many covered writers will not roll an

option position unless they can do so for a credit. That is not a bad practice,

since taking in additional premium will always have the net effect of lowering

your risk. However, if you need to write a new call more than five to seven

months away in order to generate a credit, you may want to think twice about

whether that makes sense. A sensible rule of thumb to follow is that if you

would not ordinarily consider selling a particular call against your stock

position, then you shouldn’t roll out to that call, either.

Rolling Down

As you might expect, rolling down is a

more defensive follow-up action. Suppose that instead of rising, DEF drops to

$25 in January. If you are afraid that it might fall further in the next month,

you can close the whole position and absorb your loss, or you can roll your

option down to the Feb 25 calls.

TABLE 4.4 Rolling Down

|

|

Original

Scenario |

New

Scenario

|

|

Premium received (points) |

2 |

2-0.35+2

= 3.65

|

|

Potential gain from stock (strike

price less initial stock price) |

30-28 = 2 |

25-28 =

-3

|

|

Total potential gain from stock and

options |

4 |

0.65 |

|

Break-even stock price (initial stock

price less premium earned) |

$26 |

$24.35

|

|

Time period |

Feb

expiration |

Feb

expiration |

When you drop to a lower strike price,

you should always be able to receive a credit, since the lower strike price

will inevitably have more premium than the one you are covering. (If for some

strange reason, it does not, then you would gain nothing from the move.)

The rationale for rolling down would be

that the stock has declined and you are willing to give up some additional

upside potential in order to protect your position more on the downside. Assume

in our example that the stock drops and the Feb 30 call can be repurchased for

0.35. If the Feb 25 call can then be sold for 2, you can take in another 1.65

credit, or $165 per contract, by rolling down. The comparison looks like Table 4.4.

You will now have removed almost all of

your upside but will have lowered your breakeven point. As with the scenario

above, you could also roll down and out by going to the March 25 or even April

25 call for even more premium. Rolling down and out, however, is still

defensive, and since it limits the potential gain from the stock during the

option’s life, it may prevent you from capitalizing on a recovery in the stock

price. In fact, one danger in rolling down is that you may lock in a loss on

the stock if, as in the example, the new strike price is below the price at

which you originally bought the shares and you are assigned. If you are that

bearish on the prospects for a particular stock, you might be better off

closing the original covered write altogether or just rolling down within the

current month to see what happens in the short term.

Rolling down can also be used as a

safety procedure when executing very short term call writing trades on stocks

with high implied volatility (for more aggressive investors). There are

frequent opportunities for buying stocks and writing ATM or ITM calls within

days of expiration for a potential 1 to 2 percent return. These opportunities

have even become more prevalent now that weekly expirations have been

introduced. One such example that occurs as we are writing is Morgan Stanley

(MS). The stock recently closed at $28.98 and has a 29-strike call with five

days to expiration selling at $.58. That would represent a 2 percent return for

the week if the stock remains at its current price or moves higher. When you

put on this ultra short-term covered write, you already have 2 percent downside

protection to start. If the stock moves higher during the week, you need do

nothing. If it trades down say half a point, you can hold, but you would not be

protected for any further decline. If you suspect further decline during the

week or simply don’t want to take the chance, you could buy back the 29 call

and roll down to the 27.5 call. Your original net cost for the covered write

was 28.40 (28.98 for the stock less .58 for the call), so as long as you can

get at least .90 credit when you roll down to the 27.5 call, you will break

even—as long as MS does not fall below 27.5 at expiration. A quick look at

theoretical values with the same implied volatility says that if MS traded down

to 28.5 with three days to go, you would be able to roll down for .90 credit.

In this manner, you looked to make 2 percent on your money for the week on any

upward move, and you were able to protect your initial investment for up to a 5

percent loss on the stock. The ability to roll down is what puts the odds of

this trade in your favor.

Rolling Out

Rolling out (i.e., keeping the same

strike price and neither rolling up nor down) has less to do with movement in

the stock than with time. The most common situation in which you would do this

is when you are approaching expiration and the stock is close to the strike

price, whether just below or just above. Assume it is now the Friday morning

before February expiration and DEF is trading at $29.95. The February 30 call

might sell for 0.15 at this point. If the stock closes under $30, the option

will expire worthless, and you could look to write the March or April 30 call

on Monday. But the stock could just as easily close at say $30.25, in which

case you would be assigned and your stock called away. Now, you may be ready to

jettison DEF from your portfolio, in which case you are hoping it does get

called away. In that case, no action is necessary. If, on the other hand, you

like DEF and plan to write another call on it anyway, you may want to roll the

option out to March and not worry about whether it closes above or below $30,

or whether it opens higher or lower on Monday. Assuming you were planning to

write the March call anyway, the additional cost of this move is the $15 per

contract you must pay to close the February 30 call, plus the transaction cost.

When rolling out at the same strike price, you will always take in more money

than you spend, because the more distant option will inevitably have more time

value. So you will be receiving money (rolling for a credit), but you should

still view the cost of the purchase as an added expense, since it will reduce

what you receive from the new call you write. It may not seem like much to buy

back a call for $15, but if you did that enough times during the year, it could

add up.

Your approach would be similar if the

stock was trading slightly above the strike, at say $30.25, even several days

before expiration. If you plan to hold the stock and write the March 30 call at

expiration anyway, then you could roll out to the next month at this point

instead of waiting for expiration. This is also commonly done when you expect

to be travelling or busy and do not want to be worrying about expiration.

Summary on rolling:

- Rolling:

The process of closing the short call position in a covered write and opening

(substituting) a different covered call position on the same stock.

- Rolling up: Substituting a call with a higher strike price.

- Rolling down: Substituting a call with a lower strike price.

- Rolling out: Substituting a call with a more distant expiration.

- Spread order: A single order that involves both a purchase and a sale of

options of the same type on the same stock for a specified “net” price.

By accepting such an order, your brokerage firm guarantees that both sides will

be executed together as long as your net price can be met. Otherwise nothing is

done. Covered writers frequently use spread orders to roll their option

positions.

- Net price: The combined price of a two-sided transaction involving the

purchase and sale of either two options or a stock and an option.

- Net credit: If the price of the sell side is greater than the price of

the buy side, then the result is a net credit.

- Net debit: If the price of the purchase is greater, then the result is

a net debit.

Other Considerations

Thus far, the discussion on rolling

assumes that you are in a fully covered write and that you roll to a similar

position by selling the same number of new calls as you were previously short.

This will be the most frequent case, but you can roll for fewer or more

contracts if you desire (although if you write more than you have shares to

support, the extras are not considered to be covered). Say you have 1,000

shares of a stock and have written 10 covered calls and decide to roll them.

Whether you are rolling up, down, or out, you may decide to write only seven

calls, particularly if you can still get a credit for doing so. Similarly, if

you were not fully covered to begin with—you had written only five calls, say,

on your 1,000 shares—you could roll those five into, say, seven or even 10 new

ones to cover your cost. The latter strategy is called partial writing and is

discussed further in Chapter 5.

When judiciously implemented, rolling

adds a tremendous amount of flexibility to covered writing, but too much of a

good thing can be dangerous. If you are continually rolling positions, it may

be appropriate to reconsider your original parameters for initiating covered

writes. Some people, for example, will put on a covered write with a stock at

$29.50 and sell the 30 strike call; then, as soon as the stock goes over $30,

they look to roll. This will threaten the advantages of the strategy by adding

unnecessary transaction costs over time.

Behavioral Issues

In the book Far From Random, we

discussed the results of behavioral finance studies that describe how a complex

array of human emotions, predispositions, and biases enter into our financial

decisions. When investing in stock, among the more prominent emotional issues

you will encounter are: loss aversion (taking action against your best

interests to avoid realizing a loss on a given stock); disposition effect

(reluctance to sell a stock once you’ve bonded to it); and mental accounting

(assigning a different value to money in one place over money in another). When

you add covered calls to the investment mix, you change the behavioral

perspective of simply owning stock and these emotional factors can change. Some

of these changes are positive, and are the reasons why you write covered calls

in the first place. Having less anxiety, for example, with day-to-day

volatility is the biggest positive.

But there are also some issues that can

become negatives. For one, it can be easy when your stock is sitting at say $70

per share for days to accept $3 for a two-month call option at 70. The

annualized return on that call premium is more than 25 percent. But if the

stock then runs to $75 at expiration, you may end up with a case of seller’s

remorse. Even worse, you are now faced with an emotional dilemma. Despite the

fact that you are ahead of where you were when you initiated the call write

(your net position then was worth 70 and it is now worth 73), you are going to

have to repurchase the option at a loss (since it would now be worth 5) if you

do not want to lose the stock to assignment. This typically results in a case

of loss aversion—one of the most powerful emotions in behavioral finance—and

one that is made even more acute by the fact that you have to make a decision

by expiration or you will lose the stock. (Some people will opt to lose the

stock simply to avoid booking the loss on the call option, even if they feel

the stock has further upside potential or if they incur a tax liability by

doing so.) At least with stock by itself, you can avoid taking a loss by simply

deciding to do nothing and hanging on to the stock.

Another emotional issue arises from the

misperception that the call provides downside protection in the same amount

throughout the life of the option. If your call write is reasonably long-dated

and the stock declines sharply in the near term, you may not receive as much

protection as you think. For example, a long-dated call might have $5 of

premium, causing you to perceive that you have 10 percent downside protection

on your $50 stock. While you do have 10 percent protection, it is over the life

of the option, not immediately. Should your stock drop to $45 right away, your

option might only drop by a couple of points, since it will still retain time

value for its remaining life.

Also, writers frequently experience an

unreasonable fear of being assigned. Some investors write OTM calls against

their stocks and then start getting nervous as soon as the stock moves up and

the call becomes ITM. Such fear is not justified by the reality of early

assignments, which are actually quite rare and which can be prevented quite

easily by rolling the position. Nonetheless, people who write calls to reduce

their anxiety and then end up simply trading anxiety over volatility for

anxiety over assignment are probably not going to have a positive experience

with covered call writing.

Differing Approaches

Your approach to covered writing can be

short term or long term, conservative or aggressive, active or passive, and as

unique to you as your signature. Between the myriad different stocks you can

write calls on and the different ways you can structure your positions by

varying option strikes and expirations, you have the flexibility to develop a

highly original implementation of the covered writing strategy in your own

portfolio. What’s more, you can modify this implementation over time as market

conditions or personal considerations dictate.

Incremental Call Writing

Before converting their investment

strategy entirely to covered call writing, most people commonly adopt call

writing on an experimental basis, attempting to enhance the returns or protect

gains on existing stock positions. This is also sometimes referred to as

overwriting. It is the simplest form of covered call writing, since the stocks

are already in place and you only need to find an appropriate call to write.

Underlying this approach is the philosophy that stock picking and covered call

writing are independent activities—you buy stocks for their long-term

potential, and you selectively write calls on them when the situation

merits—usually when you feel upside is limited and are in a more defensive

posture concerning the stock or the overall market. The strategy typically

involves writing OOM calls when looking to enhance returns and ITM or ATM calls

when in a more defensive mode.

Examples of circumstances that lend

themselves well to incremental call writing include:

- Increasing income. You hold a stock that you picked up at $28 and that has

traded between $20 and $40 over the past 18 months. The share price is now $30.

You have finally decided that if the stock gets back up to $35, you’re going to

take your 25 percent gain and sell it. Once you can say that to yourself, this

becomes a covered write candidate.

- Establishing a target price. You have a stock that tends to trade

in a range, and it is currently near the top of that range. Rather than sell

your shares while they are high, hoping to repurchase them later, at the bottom

of the trading range, you might find a call option with a strike above the

current share price and take that premium in as income. Say that, as above, the

trading range is $20 to $40 and that the stock price is now $38. You might sell

a call with a 40 strike. If the stock pulls back, you get to keep the premium.

If it breaks out of its range on the upside and exceeds $40, you could let it

get called away or roll the option out and up to a higher strike price.

- Reducing volatility. You hold a substantial number of stocks on which there are

listed options and would like to reduce the volatility of your portfolio by

bringing in income on some positions. Or you may simply feel that the market

will remain relatively flat for some time because of the overall economic

climate.

- Long-term holdings. You own a stock that you may have inherited or simply held

for a very long time. It has low cost basis and you prefer not to sell it, but

it’s been languishing as a performer. You can write OTM calls on the position

for additional income and minimal risk of assignment.

Traps Involved in Writing for Incremental Return

These can all be reasonable approaches,

but they contain traps for both individuals and professionals who use them.

Although relatively easy to implement, the incremental income approach to

covered writing can disillusion some who try it. The crux of the matter is the

expectation that additional income generated by selling calls on existing

stocks is “free” money—like getting a quarterly dividend on the stock.

The trade-off in lost upside potential too often gets lost in the logic. At

some point, one or more of the stocks will exceed the option strike price at or

before expiration. The stockholder will then have to buy back the call before

it expires (perhaps at a loss), or have the stock called away, or need to roll

the position. The assignment could create an unexpected tax liability on the

stock if there is a capital gain. None of this is truly bad news unless one

expects that it will never happen. The lure of this so-called “free money” approach was behind the creation of several mutual

funds in the 1980s. The idea was that the fund managers would create a

portfolio of quality stocks with reasonably high dividends, such as utilities,

and then write call options against them to further enhance the income. These “option income” funds were positioned as hybrids between fixed-yield

and regular stock funds, and they were targeted at conservative investors

looking for an attractive yield plus the opportunity for some additional

growth.

Most of these funds eventually

closed—not because they lost money, but because they failed to deliver the

promised attractive yield with upside growth potential. The yield was there,

but the growth lagged that of the general market during the period. The funds

also had problems with executions. Managers tried to write far out-of-the-money

options on the premise that these would leave plenty of upside and that,

however small the premiums earned, they would still enhance returns. But

high-dividend stocks (frequently utilities) tend to be less volatile. They therefore

have lower option premiums and tend not to have strike prices much higher than

where the stock currently trades. So the funds gave up significant upside

appreciation for a meager amount of additional yield. This is not to say that

writing incremental calls on an existing portfolio is ineffective. It’s just

important to manage one’s expectations about the benefits and consequences of

such a strategy.

Other traps to watch out for are

discussed below. The biggest potential problems stem from the fact that those

writing calls for incremental return tend to do so based not on scientific

factors but on subjective “feelings” that

although a stock has an attractive long-term upside, its near-term prospects

are not great. This can lead to mistakes such as the following:

- Writing calls at the wrong times. Incremental writers tend to write calls intermittently, based on a stock’s past behavior rather than on its anticipated behavior. An example of this is writing calls on a stock that has not moved appreciably in some time. If the stock has been relatively flat for several months, its volatility, and hence the premiums of calls written on it, will be somewhat lower than usual. If it continues flat, then writing a call could prove beneficial, but if it breaks out of its doldrums on the upside, you may have given up some of that upside for a lower-than-usual amount of call premium.

- There is a similar tendency not to write calls on a stock that is moving steadily up. Yet this is when both volatility and the price of the underlying stock may provide you with the best opportunities to capture option premium and also realize gains on the stock. The bottom line is that you can never know for sure whether writing a call will be more beneficial than simply holding the stock during the same period until expiration. So if you’re waiting to decide whether to write, you are basing your decision on past performance rather than what may happen before the next expiration.

Believing you can time the market. If

you sell calls only when you “feel it is safe” (that

is, when you believe your stock won’t rise enough to be called away), you are

in dangerous waters. Few people succeed at this assessment consistently over

time, particularly if they are operating largely on gut feelings. Say you buy a

stock at $40 because you believe it will be priced between $60 and $70 in a

year or so. Six months later, the stock is trading at $46. You decide that at

the rate it’s been moving, you can write a two-month call option at a strike

of 50 for, say, 1.50 and not have to worry about your shares being called away.

One month later, the stock breaks out and runs to $54. Stocks rarely exhibit a

nice steady increase each month just to accommodate your strategy. So, your

stock is on track to achieve your long-term objective, but you have given up

any appreciation above $50 for another month. You can recapture this

appreciation by rolling up and out, but the point is that you tried to time the

market with your covered write and it did not work to your benefit. Meanwhile,

you elected not to write during the first six months, when you could have taken

in premiums at the 45 or 50 strike prices without being called away.

The Total Return or "Buy-Write" Approach

The alternative to writing for

incremental return is to specifically select stocks that are attractive as

covered writes, seeking total return from stock appreciation plus a continuous

flow of option premium. When you have decided to grow your overall portfolio

over time in this manner, then you will have embraced the total return, or

buy-write, approach to covered writing. This is simply the generalized approach

that seeks growth through the total opportunities presented by both a stock and

its call options together, and that recognizes covered call writing as your

primary ongoing investment strategy. In doing so, you concentrate your research

on stocks that have listed options and determine which are attractive not just

on their own merits, but in combination with their call options. This could

mean rejecting a stock that you like fundamentally but for which there are no

options, or choosing to establish a covered write on a stock that you might not

have invested in by itself. By using at-the-money and out-of-the-money calls in

different months, you can adjust the strategy to achieve a balance between

option premium and potential stock gain with which you are comfortable.

There is a substantial difference in

orientation between the incremental and the total-return approaches. Stock

selection is different, timing is different, and ongoing portfolio management

is different. If you are astute, you might be able to mix the two strategies,

but when you do, you subject yourself to the traps inherent in both. In the

total return approach, you select both stocks and calls based on their

attractiveness as part of a covered write. This is a departure from selecting

stocks based solely on their long-term fundamentals and business prospects. As

a covered writer, you also want positive fundamentals, but you can loosen the requirements

quite a bit in terms of price and time objectives, since the stock simply has

to have a strong likelihood of being above the strike price of the call by

expiration. Furthermore, the call premium has to be attractive relative to the

stock price and to the call’s theoretical value.

Total-return investors don’t have to

guess when it might be appropriate to write a call. Their approach is

predicated on the strategy’s ability, over time, to produce consistent returns

without guesswork. They can use fundamental research to help pick stocks, but

not in the same way—or with the same objective—as the incremental writer. Thus,

the objective in total return is not to buy a stock for $40 that has the

potential to trade between $60 and $70 in one or two years. The objective is to

buy a stock at $40 and write a 40 or 45 call based on the judgment that the

stock is likely at least to remain where it is, if not go higher, in the next

month or so. There is therefore a stronger need for the investor to feel confident

that the stock won’t drop to $30 in the next month, than that it will attain

the far more ambitious (and often more elusive) goal of rising to $60 in the

next year. A solid fundamental picture helps lower the possibility of a sharp

decline. But covered writers should also study technical trends and support and

resistance points to determine likely scenarios for the duration of their

option positions.

Buy-writers can identify potential

investment opportunities in two ways: (1) by identifying stocks they really

like and seeing whether they have options traded on them; or (2) by screening

all the attractive covered writes to find those involving stocks they like.

Since options are available on only a relatively small percentage of stocks,

this latter method is the more efficient and can be accomplished using software

programs or Internet-based services. As a buy-write practitioner, once you have

become familiar with a number of optionable stocks, chances are you will return

to that group again and again for new ideas when funds are available. If, for

example, you like the fundamentals on Apple Computer and establish a covered

write only to have your shares called away after a month or two, you are likely

to find subsequent opportunities in Apple during the following months. In fact,

it is common to re-establish a position in some of the same stocks repeatedly

when the share price and the option premium appear attractive.

Investors who take the total-return

approach to covered writing range from quite conservative to highly aggressive.

The conservative investor would select less volatile stocks and write calls

that are closer to being at the money and a little farther out in time. The

aggressive investor would look for stocks more likely to make big moves and would

write out-of-the-money options in nearby months. Of course, there is nothing to

say that you can’t do some of both or vary your posture over time.

Traps in the Total-Return Approach

Like the incremental-income approach,

the total-return approach also has its traps. Key among them are the following:

- Writing the highest premium. If you are looking for covered writing

opportunities, you will see numerous situations in which option premiums appear

exorbitant and offer highly attractive potential returns. The problem is that

very often these candidates are highly volatile stocks or stocks that have

speculative fever built into their prices. High premiums can have any number of

causes. They may even be a bearish indicator. When there is the possibility of

a downside move—say, in the event the company is named in a substantial

lawsuit—put options are likely to increase in value as large stakeholders buy

them to protect their positions. In such situations, arbitrage among the puts,

calls, and the underlying stock will generally cause the call premiums to rise

as well. In other words, the calls increase in value as a result of the

likelihood that the stock will decline. If you go after these situations, you

may be in for more of a ride than you bargained for.

Too much focus on the option, not

enough on the stock. When writing covered calls, it’s easy to lose sight of the

fact that the stock is your main investment and that it holds virtually all

your downside risk. An attractive premium should always be evaluated in

relation to the underlying stock’s prospects. You should keep in mind that if

the share price declines, you can lose money despite the premium income

(although still less than if you owned the stock by itself). This typically

occurs with volatile stocks that have options two or three strike prices above

the current share price whose premiums seem high. Say such a stock is trading

at $46 and you can get 1.50 for a two-month call at the 55 strike price. This

may provide a whopping return if exercised, but it will not offset the downside

risk of the stock trading below $44.50.

Unrealistic expectations for returns if

exercised. When looking for covered writes and ranking them by potential

return, you will see some with huge potential RIEs. This can occur with any

highly volatile stock that has call options with strike prices well above where

the shares are currently trading. The calls often provide attractive premiums

while still allowing significant upside gains on the stock before being

assigned. It is easy in such situations to lose sight of the fact that volatile

stocks present greater downside risk as well. In the example above, the return

if exercised for the 55 strike call would be 22.8 percent ($9 on the stock plus

$1.50 for the call, divided by the purchase price of $46) in two months. Sounds

terrific. But what is the reasonable likelihood of the stock reaching that

strike price in 60 days? The return if unchanged on this position is only 3.2

percent.

Not writing continuously. Total-return

writers can fall into the same trap incremental writers face—that of trying to

guess when to write and when not to. If you buy a stock because it represents

an attractive covered write and then decide not to write another call when the

first one expires, you are defeating the purpose of selecting that stock to

begin with. Even in the above example, where the static return was 3.2 percent,

by not writing that call, you would be losing out on premium that annualizes to

more than 19 percent. The same observation holds for situations where you are

assigned but do not reinvest your proceeds in a new position right away.

The main point here is that many of the

benefits that accrue from covered writing stem from the discipline that the

strategy imposes. You can mix strategies or even modify your strategy over

time, but if you are not clear about your implementation, chances are you will

have difficulty maintaining discipline and will fall into one or more of the

traps mentioned above. Whether you are writing for incremental return or total

return, your overall success in, and satisfaction with, covered writing are

greatest when you are clear about your implementation and mindful of the traps.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 4: Implementing Covered Call Writing : Tag: Options : Summary on rolling, Define rolling options, Define Follow-Up Actions, Define Behavioral Issues, Define Differing Approaches - Options Trading: Implementing Covered Call Writing

Options |