The Basics of Covered Call Writing

Options strategies, Capital, Market, Risk/Reward, Exchange-traded funds

Course: [ OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 3: The Basics of Covered Call Writing ]

Options |

Covered call writing—the basic practice of selling call options on one’s stock holdings is the grandfather of option strategies. It is a conservative, multipurpose strategy that effectively transfers some of the risk from holders of stocks to those looking to take on that risk with limited capital.

THE BASICS OF COVERED CALL WRITING

Covered call writing the basic practice

of selling call options on one’s stock holdings is the grandfather of options

strategies. It is a conservative, multipurpose strategy that effectively

transfers some of the risk from holders of stocks to those looking to take on

that risk with limited capital. It was the desire by institutions with large

stock portfolios to hedge their holdings that provided the genesis of the

options market in the United States. With a growing inventory of call option

contracts offered by institutional clients, brokerage houses generated demand

among public investors to purchase the contracts by advertising their

availability in the newspaper. When it was clear that a formal, standardized

market for such instruments was needed, the Chicago Board Option Exchange

(CBOE) opened its doors to trade call options, in 1973. It would be four years

later that the CBOE added put options.

Practiced by individual, professional,

and institutional investors, covered writing aroused heightened interest in the

institutional investment community as a result of analysis published by the

Chicago Board Options Exchange in the spring of 2002. In May of that year, the

CBOE then created a new benchmark called the Buy Write Index (BXM), which

simulates an ongoing covered call-writing strategy on the Standard & Poor’s

500 Index. Extending the BXM back in time showed that the average annualized

return hypothetically generated between 1988 and 2001 by a basic covered

writing program would have been less than half a percentage point below that

produced by owning the S&P 500 basket of stocks, but with approximately

one-third lower volatility in monthly returns.

Since becoming listed securities, call

options have been used by a wide array of portfolio managers to reduce the risk

in stock portfolios of institutions such as insurance companies, endowments,

and pension funds. Unfortunately, it was difficult for individual investors to

take full advantage of the technique for many years due to high transaction

costs and limited access to electronic information, but that has now changed

with the advent of discount brokerages and online access to stock and option

data through the Internet. Now, covered call writing not only represents a

viable investment technique for just about any stock investor, but is even more

useful as the volatility in stock returns continues to rise. Now, covered

writing is not only an attractive practice for those who already own stocks, it

has also become a viable strategy in its own right for those who want to

specifically create a stock portfolio for the express purpose of writing

covered calls on a continual basis.

Variations of covered call writing

abound and can be used at different times or under different circumstances.

Moreover, call writing forms the basis for more complex option strategies that

include other positions in combination.

Requirements for "Valid" Covered Writes

Call options of any available expiration month and strike price may be sold to create a covered write. The combined position can be of any size (100 shares and 1 contract, 2,500 shares and 25 contracts, 25,000 shares and 250 contracts, and so on), and the two parts may be initiated simultaneously, or call options can be sold on a stock position already in your portfolio. To be deemed a valid covered write by your brokerage firm for margin purposes, the two component positions must exhibit the following characteristics:

- Both the stock and the options must be in the same account. You may not, for example, have the stock in your individual retirement account and write the call in your regular account.

- The stock held must be the underlying security specified by the short option or a security that can be converted into the underlying, such as a warrant or another option. If you are going to write a call on ABC stock and have 20 other stocks in your account worth far more than 100 ABC, your ABC call would still be considered naked unless you were long 100 ABC in the account.

- You must hold at least enough shares of stock to fulfill the delivery requirement of the call option. Unless otherwise adjusted, each call option represents 100 shares of the underlying stock. Therefore, if you sell five calls, anything less than 500 shares will leave one or more of those calls uncovered. Having more than the requisite number of shares to deliver if assigned is not a problem.

These criteria are not just academic.

They determine whether you will be subject to a margin requirement or, in some

cases, whether you will be permitted to maintain such a position in your

account at all. Only fully covered option positions, for example, are permitted

in cash or retirement accounts.

Risk/Reward of a Covered Write

Although they show as two separate

positions in your account, the two parts of a covered write effectively form a

new hybrid position that offers risk/reward characteristics different from

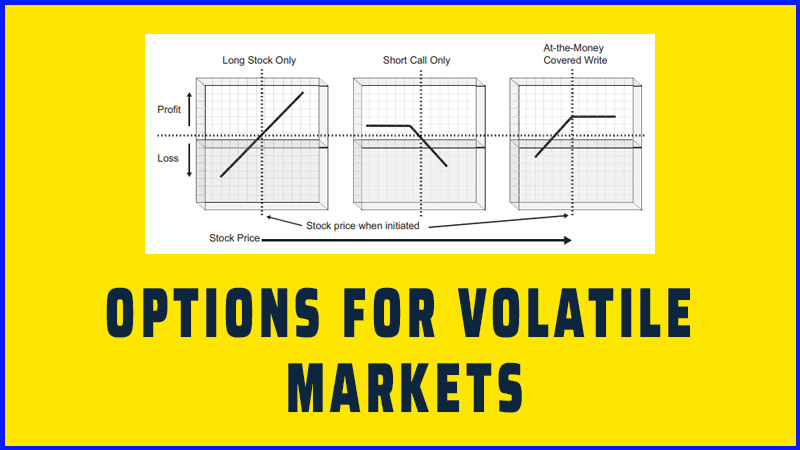

those of either of its components. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

A long position in XYZ stock by itself

has dollar-for-dollar opportunity on the upside as well as dollar-for-dollar

risk on the downside. In other words, every dollar rise or fall in the stock

price represents a dollar gain or loss for the investor. While your gain on a

stock position is theoretically unlimited, the maximum loss is whatever you

paid for the shares. A short call position with no accompanying stock position

is considered naked and highly risky. Its maximum gain equals the net premium

received from the sale of the call, and its loss is theoretically unlimited

should the price of XYZ shares rise substantially. That’s because, in order to

deliver the shares represented by the option if it is exercised, you would have

to buy them in the market, so the higher the stock’s price rises above the

strike, the more you would be out of pocket.

FIGURE 3.1 Risk/Reward of a Covered Call

Write

A simple at-the-money (ATM) covered

write (option strike = current stock price) reduces the downside risk of the

stock alone and completely eliminates the upside risk of the short call. The

cost of the stock position is reduced by the amount of the premium earned from

selling the call. This lowers your breakeven point—the share price at which you

neither gain nor lose money—and also reduces your maximum potential loss. Since

you don’t have to go to the market to fill an assignment on the short call,

you’ve eliminated the risk posed to the naked call writer by a strong move

upward in the stock.

The trade-off for the reduced risk of

the covered write is a limited upside potential. An ATM covered write has a

potential upside equal to the amount of option premium received. The potential

upside of an out-of-the-money (OTM) covered write stems from both the option

premium and any gain in the stock, up to the strike price. By varying the

strike price of the call option, covered writers can balance potential gain

against risk reduction to suit their objectives. In addition, the covered call

will realize at least some profit over a wider range of stock prices than

either component by itself.

Now consider the following example of

positions initiated two months before option expiration:

Long

100 XYZ at $48.

Short 1 XYZ

Nov 50 call at 2.

Figure 3.2 plots the returns at expiration for the covered write

combining the two positions above against those from a long position in the

stock alone. It shows that, while giving up some of the potential upside

enjoyed by the stockholder, the covered writer enjoys a better return for all

stock prices up to $52 during the period. If the stock price is below $50 (the

strike) at expiration, the gain on the covered call exceeds the stock return by

2 points, the amount of the option premium. Once the stock price reaches $50,

the difference narrows until the share price reaches $52, the strike price plus

the amount of the option premium. At a share price of $52, the covered write

and the stock generate the same return; for all prices above that, the gain on

the stock alone would be greater. Thus, $52 is the crossover price for the two

strategies.

Purchase

Stock = 48.

Sell

Call = 2.

FIGURE 3.2 Risk/Reward of Long Stock Call

Write

Table 3.1 summarizes the profit/loss characteristics of all three of

the positions from the example.

Risk/Reward Characteristics over Time

The previous illustrations can be found

in many texts on options. They are helpful for understanding the basic risk/reward

characteristics of buying stock and selling a covered call option, but only

when the position is held until expiration. They ignore the fact that

risk/reward characteristics for covered writes can be modified over time and

thus fall short of describing the risk/reward features of covered writing as an

actively managed ongoing investment practice.

TABLE 3.1 Long Stock versus Call Write

|

|

Long

Stock (Alone) |

Short

Option (Alone) |

Covered

Write |

|

Maximum Gain |

Unlimited |

2 |

4 |

|

Maximum Loss |

48 |

Unlimited |

46 |

|

Break-Even Stock Price |

48

(Losses start below this price) |

52

(Losses start above this price) |

46

(Losses start below this price) |

When you buy stock, your risk/reward

remains constant until you dispose of it. That could be a day, a month, or 10

years. It doesn’t matter how long the holding period is or where the stock goes

during that time. If you buy the stock at $48, as in the above example, and it

goes to $120 in six months, you have an unrealized gain of 72 points, but

unless you sell it, your breakeven on the initial investment and your potential

gain or loss do not change.

Assume instead that you initiate the

above covered write in XYZ, and at option expiration in November, the stock is

trading at 49. The November 50 call expires worthless, but you still own the

stock. You might now be able to write a January 50 call at 2. What happens if

you do that? You reduce your maximum loss, lower your breakeven, and raise your

maximum gain by the amount of the new premium—to $44, $44, and $6 per share,

respectively. So, you start out by initiating a position that has less risk

(although also less profit potential) than owning the stock by itself. Then, a

couple of months later, you take in more option premium, reducing your risk

even more and adding to your profit potential. This scenario, pictured in

Figure 3.3, illustrates how multiple writes on the same stock position further

reduce its risk and boost its gains. It is in this manner that covered writing

enables investors, over time, to approximate the returns of owning stock but

with less risk.

Of course, the underlying stock will

not always be accommodating enough to remain flat, giving you a chance to write

a second call with the same strike price. However, regardless of whether the

stock price goes up or down after the covered write is initiated, there are

follow-up actions that the investor can take to reduce risk, lower the

breakeven, or increase the upside potential of the original covered write.

FIGURE 3.3 Risk/Reward of Second Call

Write

Unfortunately, you cannot create a

graph of the risk/reward for multiple covered writes over a long period because

there would be an infinite number of scenarios and follow-up actions to

consider. But you can examine how any specific follow-up action will alter the

risk/reward of an existing position, as shown above. This is discussed further

in Chapter 4.

Risk Transference

Call buyers provide the fuel for the

covered writing engine by purchasing, for a limited period of time, the upside

potential of a particular stock beyond a specified stock price. The appeal of

buying a call is, of course, the ability to enjoy substantial upside potential

with a limited investment and consequently a limited potential loss.

The call buyer knows that the process

will lose money frequently, if not most of the time. That’s because, for the

position to gain, the stock must not only go up but must go beyond the call

buyer’s breakeven point—the strike price plus the call premium by expiration.

In reality, call buyers do not generally hold their calls until expiration,

preferring to take short-term profits if the underlying stock moves in their

favor. Regardless of whether they hold to expiration, however, they hope that

over time even a few substantial gains will offset the losses they know they

will also sustain.

Call writers take the opposite side of

this game. They reap a series of small, consistent returns as time value

dwindles away on the call options they sell. Since covered writers own the

underlying stock, they have complete protection from upside loss on the call

option, incurring only an opportunity loss when the stock goes up. They do, of

course, still have the downside risk of the stock itself.

Covered writers are thus stockholders

who, for a given period, would rather have a known income received immediately

than an uncertain upside. This income is the owner’s to keep regardless of the

stock’s price movements. As such, it will always mitigate the downside risk in

the stock position during the period. Covered writers know that the upside potential

of the strategy is not as great as holding the stock by itself for the same

period, but they also know that the option premiums will provide a greater

return than simply owning the stock when the stock price goes down or remains

flat.

The Effect of Exercise and Assignment

As noted in Chapter 1, all options on

individual stocks and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) trade American style,

meaning that an option holder can exercise anytime before expiration. That in

turn means that a covered call writer can receive an assignment notice at any

time, triggering the sale of their underlying stock. This may seem like a

serious concern, especially for stock holders who are writing calls against

positions they would prefer not to sell, perhaps because it would create an

undesired tax liability. In fact, early assignment is not a particularly

serious problem, since in reality, while early exercise is possible, it will

only occur under certain circumstances, and by remaining alert to those

circumstances, the covered writer can avoid such an occurrence. (Those who are

writing calls on stock they do not wish to sell need only be more alert to the

possibility of an early assignment and take follow-up action accordingly.) In

fact, it is generally good news for a writer to be assigned before expiration

because that accelerates, and therefore increases, his or her return. It is

like having a bond called before maturity.

While calls can be assigned at any

time, they will not be unless or until it is in a holder’s economic interest to

exercise. The key, therefore, to determining when an early exercise is likely

to occur is to understand when it would benefit the holder and when it would

not. First of all, call holders are generally speculating that the price of the

underlying stock will rise enough to create a profit on the option before it

expires, and what they really want is not to exercise the option but to close

out for a profit before expiration. They rarely buy calls as a means of

acquiring a stock, and they don’t want to incur the additional commissions

involved in exercising and selling the shares. It is therefore seldom in a call

buyer’s interest to exercise before expiration.

Secondly, it is economically unwise to

exercise a call when the option is out of the money (i.e., to buy shares of

stock via exercise at $45 when it is selling in the open market for say $41.)

Such a move is not in the holder’s best interest, regardless of what he or she

may have originally paid for the option. This is true even when the stock price

rises and the call option you my have sold goes into the money. Say your option

is the 45 call and the stock is now trading at $50. Theoretically, you could

exercise and immediately sell the stock, thereby capturing the five points of

intrinsic, or cash, value. But options tend to carry some amount of time value

right up until the last few days or hours before expiration, even when they are

in the money. As long as a call option has time value (regardless of whether it

is profitable to its holder or not), a holder will always receive more money by

selling it than by exercising and selling the stock.

For example:

DEF stock is trading at $53.

DEF Aug 50 calls are trading at 3.75.

If you held the DEF call, it would be

unwise to exercise, even though it is in the money because it still has 0.75 of

time value that you would give up by exercising. You would be better off

selling the call at 3.75 and buying the stock in the market at $53. That way,

you would end up with a net cost of $49.25 a share for the stock, compared with

$50 if you exercised. (In reality, you would also consider commissions in

determining whether exercising is worthwhile.)

Note that the price you paid for the

call is irrelevant to this discussion. Regardless of whether you currently have

a profit or a loss on the position, you are better off selling the option than

exercising it while it still has time value (unless the time value is so

miniscule that your transaction costs eat up that value). The implication for

the covered writer is that there is very little chance of an early exercise

while the option contains any time value. So if you are at all concerned about

being assigned, check whether the option is trading with time value. If it is

in the money and has at least 0.50 in time value, it is very unlikely to be

exercised. If it has only 0.05 to 0.10 of time value, or if the bid price is

lower than its cash value (for example, if the option in the above example were

bid at 2.90 when the stock was trading at $53), then you might be assigned early.

One factor that can sometimes lead to early assignments is an impending cash

dividend. Occasionally, holders will exercise in time to own the stock on the

record day for the dividend, but again, this will not likely happen until the

option trades very close to parity (with no time value).

At expiration, if a stock is trading

very close to the strike price, assignments may occur early, and under the

rules imposed by the Options Clearing Corporation, all options that are

in-the-money at expiration are automatically assigned. Therefore, call writers

who do not wish to have their stock called away, must take action to close the

option prior to expiration. When the stock is selling very close to a strike

price on the last day of trading before expiration, covered writers are

generally closing their positions if they do not want their option assigned. If

a stock is trading at 49.80-49.90, for example, call writers of the expiring 50

strike calls will look to close their positions prior to the close that day as

it might be possible for the stock to close at 50.05 and trigger an assignment.

It is also not uncommon to receive an

assignment notice on only part of your position early. You may, for example,

have 1,000 shares of stock and 10 short call options and receive notice of

assignment on 300 shares a few days before expiration.

The only scenario that can be even more

beneficial to you as a covered writer than being assigned is to have your stock

end up a few cents below the strike price on expiration and not be assigned. If

that occurs, you realize the maximum gain on the stock for the period, yet you

still own the stock. You do not incur the transaction costs of being assigned

and purchasing another stock, and you should be able to get an attractive

at-the-money premium for the following month to write another call on your

shares.

Calculating Potential Returns

Because the call options in a covered

write have both a defined life and a maximum potential gain (the premium you

took in from their sale), it is relatively easy to project a rate of return for

the position at various price points for the underlying stock at expiration.

Most commonly, writers will look at projected returns for two key prices on the

underlying stock at expiration: the strike price of the option and the current

price of the stock. Since this is handily accomplished by a computer for all

potential covered writes on all optionable stocks, covered writers can quickly

compare the risks and potential rewards of different writes on the same stock

or of writes on numerous different stocks, even as prices change during the

day.

Return if Exercised (RIE)

The maximum potential reward for a

covered write occurs when the stock is above the strike price at expiration and

the option is exercised. When calculating this potential, the return is

frequently referred to as the return if exercised (RIE), or return if assigned

or return if called. The RIE, which can be expressed either as a raw (absolute)

return for the period until expiration or as an annualized return, is simply

the potential gain in the stock (up to the strike price) plus the option

premium received.

Consider again the example used

earlier:

Buy 100 XYZ at $48.

Sell 1 XYZ Nov 50 call at 2.

Assume that the positions are initiated

two months before option expiration and that transaction costs are excluded.

(Note: If this were an in-the-money

covered write, strike price minus stock price would be a negative number.)

It is common to project annualized

returns from covered writes when writing out-of-the-money calls. Remember,

however, that this is the best-case scenario and that the annualized projection

further assumes that you can get an equivalent return on other writes during

the remainder of the year. It is therefore unrealistic to project annual

performance based on the formula’s results for a single covered write.

Annualized RIE is very helpful, though, as a basis for comparing or ranking

different covered writing opportunities, since it equalizes the time period in

all cases.

Return if Unchanged (RU)

A secondary (and more conservative)

calculation is also generally made on potential covered writes based on the

assumption that at option expiration the underlying stock is trading at its

present price. The result of this calculation is commonly referred to as the

return if unchanged (RU), or the static or flat return.

For an out-of-the-money covered write,

like the one in our example, assuming no change in the share price means the

potential gain in the stock will be zero.

(Note: For an in-the-money covered

write, the RIE and the RU are equal, since the stock would be called away at

expiration in either scenario.)

It is particularly beneficial to use

the annualized RU when writing calls for income, as it enables one to compare

the return from writing calls with other income-producing investments (such as

bonds), which are typically also quoted on their annualized yields.

Return Based on Net Debit

If you implement a stock purchase and

covered call write simultaneously in your account, you will be debited for the

stock at the same time you are credited with the option premium. The resulting

charge to your account for the two items combined is a single amount called the

net debit for the position. In the previous example, since you bought stock at

$48 and sold a call for 2, your account would be debited $4,800 plus

transaction costs for the stock and credited $200 less transaction costs for

the option. This results in a net debit to your account of $4,600. Thus, it

would be valid to view your initial investment, not as the full stock price,

but as the stock price less the option premium, since that is all you actually

have invested. Looking at the option premium this way (as a reduction of your

initial investment rather than as part of your ultimate returns), results in

slightly higher calculated rates of returns (the absolute return remains the

same) for covered writes, since the initial investment is smaller. In the

example above, the raw RIE would be 8.7 percent if calculated this way, rather

than 8.3 percent, and the annualized RIE 52.9 percent, rather than 50.7

percent. The difference can be much more dramatic for lower-priced stocks or

in-the-money writes where the option premium is larger. This book uses the more

conservative calculations based on the full stock price, unless otherwise

noted.

OPTIONS FOR VOLATILE MARKETS : Chapter 3: The Basics of Covered Call Writing : Tag: Options : Options strategies, Capital, Market, Risk/Reward, Exchange-traded funds - The Basics of Covered Call Writing

Options |