Single Reversal Patterns

Single candlestick patterns, Types of candlesticks, Powerful candlestick patterns, Types of candlesticks, Candlestick chart analysis, Bearish candlestick patterns

Course: [ Uses of Candlestick Charts : Chapter 3. Single Reversal Patterns ]

The first pattern we’re going to look at is the Hammer. This is a rare treat in candlestick analysis: a pattern that looks like its name!. A Hammer looks like a hammer, with a small fat head and a long handle.

An in depth look at the Hammer to see why

this is a reversal signal, and such a strong one!

Hammer

The first

pattern we’re going to look at is the Hammer. This is a rare treat in

candlestick analysis: a pattern that looks like its name!

A Hammer

looks like a hammer, with a small fat head and a long handle.

With

every candlestick pattern in the following chapters I’m going to put the set of

rules for each pattern in a highlighted box, for easy reference. You may have

already noticed the “Cheat Sheet” on the inside covers of this book - this will

hopefully become your first point of reference once you’ve finished reading the

main chapters.

Chapter summary

This is

the crux of candlestick analysis: by looking at the shape of any candlestick we

can surmise what’s happened over that time period. We can then make assumptions

on the balance of power between bulls and bears, and on those assumptions

decide whether this balance is starting to tip the other way.

Trading

and charting the markets can be classed as an exercise in playing the odds. If

you can effectively and successfully gauge market direction you are already

doing better than merely flicking a coin (which is akin to many people’s

decision making process!)

Now we’ll

go through some of the more common and more powerful reversal patterns and work

out why they’re classed as reversals.

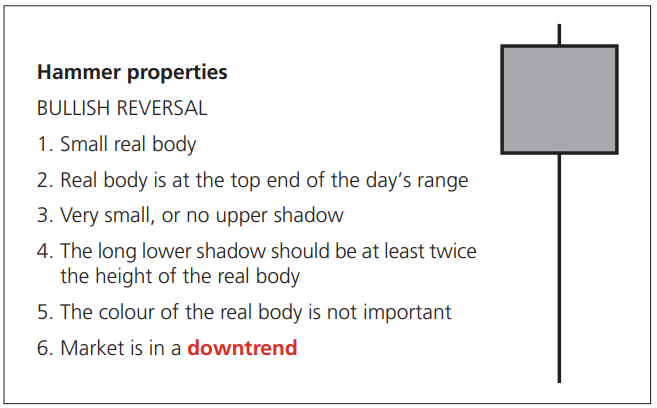

Rules

Construction

Let’s

expand on the above, just to make sure everything’s clear. Think about our

Doji: this was the result of an open and close at similar levels - an even

balance between bulls and bears. The Hammer has a small real body, so with this

pattern we have the same thing - a pretty even balance between buyers and

sellers. This is also the reason why the colour of the real body isn’t

important; it’s the size of the real body that’s important. We’ll talk about

this a bit more later on.

The small

real body is at the top end of the day’s range, so there is not much happening

above the top of the real body. This leaves us with a lot of lower shadow, and

as I’ve said in the box above this should be at least twice the measurement of

the real body. I’m never sure whether to say twice the height or twice the

length, but hopefully you’ve got the idea. Most charting systems have a cursor

functionality where you can check the open, high, low and close of the

candlestick if you put your cursor over it - you can use this function to check

if it qualifies.

The final

condition is very important and, unfortunately, often forgotten. Remember we’re

looking at a reversal pattern here, so the market needs something to reverse.

Only if we see this shape of candlestick in a falling market can we call it a

Hammer.

There is

a name for this shape of candlestick in a rising market (the Hanging Man), but

it’s not as strong a reversal signal as a Hammer and, anyway, we’re going to

look at it later on in this chapter.

The fact

is, the Hammer is an extremely potent reversal pattern and one of the simplest

to understand, which is why we’ll spend a bit of time on it. As you can see

from the following chart it certainly did a good job in this instance. This was

the August 2007 subprime sell- off in the Dow - the first time it hit the fan

anyway!

Figure 3-1: Dow Jones Industrial

Average; daily candlestick chart; 10 July 2007 - 20 September 2007, showing 16

August 2007 Hammer

We can

see clearly from this chart that the Hammer candlestick did indeed call an end

to the selling, and from here the market rallied strongly, only returning to

these levels months later.

Getting inside the pattern

Why is a

candlestick shaped like this such an important reversal? To answer this

question we need to think about the price action that goes into the formation

of a candlestick of this shape.

The best

way to do this is to zoom in on that particular day and see what actually

happened over the session, but while we do this we should also keep in mind

that the daily chart only requires four pieces of data: the open, high, low and

close on that day.

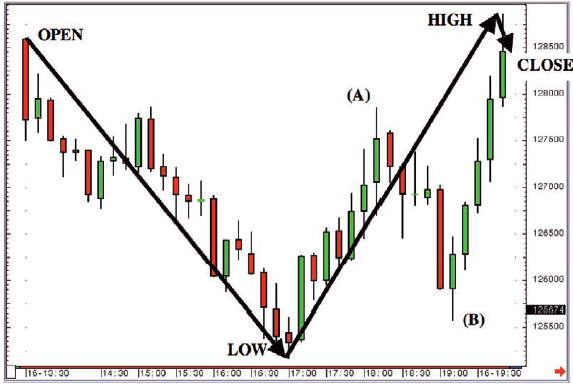

Below is

a 10-minute candle chart for the Dow Jones Industrial Average on 16 August

2007. We have added to the chart the general direction of travel, joining up

the day’s open, low, high and close.

We have

cut the day into small 10-minute segments and the following chart shows the

direction of travel taken if we split the price action down into these small

parts.

Figure 3-2: Dow Jones Industrial

Average; 10-minute candlestick chart for 16 August 2007

You can

see that on this day the market sold off dramatically - over 300 points in the

first 4 hours of trade - but then rallied strongly and took back all of the

earlier losses, closing the session right back at the highs. What a

roller-coaster ride!

So that’s

what happens on a Hammer day. It’s clear as a bell if you look at the previous

chart:

The market sold off sharply, then hit a

price where the selling stopped and the buyers took over. From here the market

rallied strongly and ended up right back where it started. It also closed near

the high, which is important, because quite often a sell off in late trade can

spoil the party. But in this case the gains seen in the second half of the

session were sustained into the close.

It could have been so different

You can

see that the bears had another go in afternoon trade on this particular day -

the sell off between the points marked A and B on our chart. But the bulls

reacted once more to this weakness and the market rallied late on and closed

strongly, leaving us overall with a “V” shaped direction of travel.

So a

Hammer on the daily chart represents a “V” shaped direction of travel over the

course of the day as a whole.

Psychology

Let’s

think about our bulls and bears and their mindset at each point of the day. At

the start when the markets begin to sell off no one is surprised, are they?

After all, the market is experiencing some selling off, which is something

we’re quite used to happening when you consider the market is in a downtrend.

Right up until the moment the market hit the low the bears are in charge, and

they’re probably very pleased with themselves. They’ve been bossing things of

late, and today they’re just doing more of the same.

Imagine,

with this level of complacency, how uncomfortable the afternoon suddenly

becomes for the bears with each tick higher. And they don’t get the chance to

get out either, because there isn’t any pullback on the close to cover

positions on. They keep thinking the market’s going to fall over again and they

can cash in some chips, but this sell- off doesn’t come.

The bulls

on the other hand, are suddenly feeling empowered, after all they’re now having

a good day (compared to how they were doing when the market was on the low),

which isn’t something they’ve been able to say much of late!

Who goes

home happier that night? I think the bulls, because finally they’ve had a good

day. Things are certainly a lot better for them now than they were when the

market hit that low earlier in the session.

The bears

will have seen their profits diminished; they’re not particularly used to this

just lately, and they won’t like it. They may well stew on it overnight, then

come in tomorrow, swallow their pride, and cover their shorts (becoming buyers

in the process). They may even decide that if you can’t beat them, join them,

and they’ll become outright bulls.

Hopefully

this gives some insight into why this sort of session can be so important and

trend changing. A Hammer represents a session where things change. Where the

sellers drop the ball, where the buyers suddenly wake up and where the balance

of power shifts from the sellers to the buyers.

In other

words, when you see a Hammer, instead of thinking that this may signal a

reversal (future tense), think of it as a sign that there has already been a

change of direction (in the second half of the session), and now the question

is whether this can be sustained, and whether it can turn into a solid change

of direction for the market you’re viewing.

Examples

Now I’m

going to roll out one of my all time favourite charts; a weekly candlestick

chart for the EUR/USD Forex cross, dating back to 1999. This was just a couple

of years into the unified currency, when the euro was almost being classed as a

laughing stock.

Figure 3-3: Euro vs. US Dollar Forex

Cross; weekly candlestick chart; 29 May 2000 - 10 September 2001

So just

to set the scene this is a weekly chart. The open of each candle is the first

trade on the Forex markets on a Monday morning in Asia. The close is the last

print on Friday night in the US.

As you

can see, the market finished each big down-leg with a Hammer candlestick, which

is all very nice, and suggests that these patterns are the best thing since

sliced bread.

Except

that’s not why I’ve shown you this chart. I want you to take a closer look and

find two more Hammers on the chart.

They

appear halfway down the first move, both together, at the end of August 2000.

The first week of September turned out to be one of the worst weeks for the

euro on the whole chart. In other words our two Hammers didn’t work. They were

without doubt the worst possible signals of a reversal.

If you

had a trading system based on buying the market on appearance of a Hammer on

this chart, you would have been stopped out by the time the good signals came

along. In fact you’d probably have abandoned the strategy altogether by then,

if you had any money left!

One

lesson we can learn from this is that we should never have a decision-making

process based purely on one candlestick pattern being posted. This is common

sense, surely. When you buy a jumper do you have one criterion, ie, “it must be

red”, and do you go out and buy the first red jumper you see? Or do you also

want to have a certain type of neck, and a specific style, and a particular

material or texture? Of course you do!

This is

where academics get it all wrong where technical analysis is concerned. To put

it in simple terms they look at something like candlestick analysis and say “we

tested 500 occurrences of a Hammer and only 100 gave us a 300 point rally after

they appeared, therefore candlesticks are rubbish.” Thanks for nothing.

Academics don’t generally wear very nice jumpers, do they? Whereas technical

analysts, in the main, are a well dressed bunch (myself apart!).

Look at Figure 3.4. Candlesticks B, C,

D and G all qualify as Hammers.

B and C

are the failed patterns that I’ve talked about above, but it’s pretty clear to

see that patterns D and G did a good job in calling a reversal. Or did they?

If you

had used the filter of needing a green candle straight after a Hammer to give

you a buy signal you would have refrained from taking buy signals at B and C,

which would have turned out to be very good decisions. More to follow on this.

But you

would have taken the signal after candlestick D at the end of the green candle

straight after the Hammer, and then would have suffered three straight weeks of

losses. In fact I’m pretty sure I would have stopped myself out at some point

during those three weeks. I hope so anyway.

After

Hammer G you would have waited for a green candle then bought, and made a tidy

profit. No issues with this one at all.

Figure 3-4: Euro vs. US Dollar Forex

Cross; weekly candlestick chart; 29 May 2000 - 10 September 2001 with

annotations

So am I

trying to say that this is great because it works 25% of the time? No, actually

it worked 75% of the time in this case, if you had waited for a subsequent

qualifying green candle.

Why 75%?

Because many of the best traders in the world will tell you that saving money,

and stopping yourself from making a bad trade, is as important as making money.

If you read interviews with top traders, such as those in Jack Schwager’s

Market Wizards, you’ll see repeated references to preservation of capital. This

introduces something important to our usage of candlestick analysis that we

haven’t even considered yet: candlesticks

can be used to stay out of bad trades as well as to get you into good trades.

Negative selection

Candlesticks

can be used for negative selection. What does this mean? If you’d been watching

this down-move with a view to waiting for an opportunity to get long, you would

have saved yourself a lot of pain, misery and money by waiting for two criteria

to be established: a bullish Hammer and a subsequent confirming candlestick. So

you had a strategy to get you into good trades as well as keep you out of bad

ones; to deselect or negatively select those that needed staying away from.

In the case of this

chart we can take it a step further and redefine our criteria to give us better

trade opportunities. We can say that if the market moves above the high from

the Hammer week, then we will go long. With this filter we would still stay out

of the market after candles B and C (a sigh of relief once again), get into the

long trade much earlier after the Hammer D (nice), and get in slightly earlier

after Candle G (still nice). Suddenly, just by applying a simple filter we have

a powerful tool to help us spot not just when trends are changing, but also

when they’re not!

This introduces another factor to the

equation: each chart will be different, and you should never treat any two

charts the same. Yes, a Hammer is often a strong reversal pattern, but what you

do with it can change from chart to chart.

This is

in spite of the fact that one of the assumptions we make as technical analysts

is that price action is repetitive; if something’s happened many times before

in a particular stock or security, we can assume it will probably happen in a

similar way in the future. In the example above we worked out that looking for

Hammers then waiting for a move through the Hammer’s high would provide the

most robust and timely signals over the life of this particular chart. We can

now apply this set of rules to the same chart in future, making the assumption

that market action is repetitive.

Obviously

this isn’t a guarantee that it will work out, but it stacks the odds in your

favour. Back testing is the name given to this exercise; going back in time to

see what worked well before, so that you can apply this in the future. I often

give seminars and talks where people gaze at me waiting to be given the Answer.

Clearly if I had the Answer I’d be in the Bahamas on my yacht, keeping the

Answer to myself. Unfortunately the answer to becoming a successful analyst or

trader is hard work, which in this case involves the back testing of patterns

to see if they’ve done the job before.

In the

following pages I’ve posted several examples of Hammers that have given us a

low, or at least a good bounce. As you can see they don’t all look exactly the

same, and sometimes they don’t actually appear right on the day the market

bottoms out.

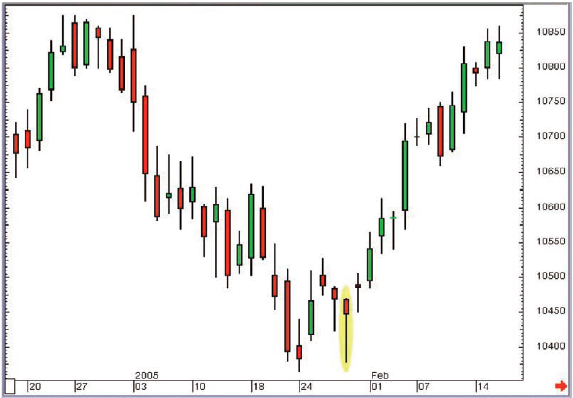

Figure 3-5: CBOT Dow futures

(unadjusted active continuation); daily candlestick chart; 17 December 2004 -

16 February 2005, showing 28 January 2005 Hammer

Note how

the Hammer pattern in Figure 3-5 didn’t actually define the low of the move,

but formed a secondary low that held the support level created by the low four

days earlier.

Figure 3-6: CBOT

Dow futures (unadjusted active continuation); daily candlestick chart; 25nJune

2004 – 8 September 2004, showing 13 August 2004 Hammer

Another

one where support was found at a support level from a few days earlier.

Figure 3-7: CBOT Dow futures

(unadjusted active continuation); daily candlestick chart; 19 September 2000 -

8 November 2000, showing 18 October 2000 Hammer

A

slightly odd looking example, but still a Hammer, and still a good reversal

signal, as it turned out.

The colour of the real body on a Hammer

Finally,

let’s address a question that’s often asked when it comes to this sort of

single candlestick patterns: does it matter about the colour of the real body?

No is the answer, and hopefully Figure 3-8 shows why it doesn’t.

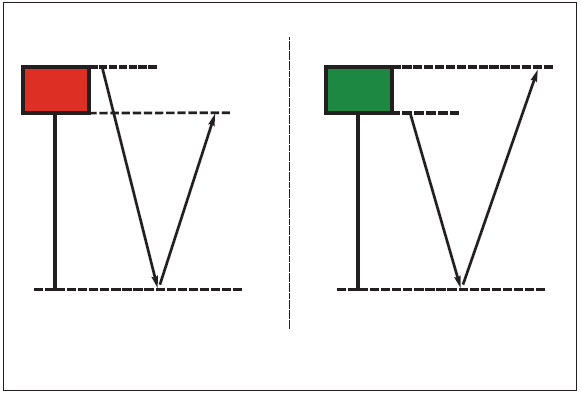

Figure 3-8: Red bodied and green bodied

Hammers; any real difference in the message?

As you

can see, in both cases the market sold off a long way, then came back a long

way. Does it really matter in which order the open and close come? The fact is

the bulls recovered from a pretty horrendous start to the day.

So no,

the colour of the real body doesn’t matter when it comes to the Hammer. Of

course there may be a slight psychological edge ascribed to a green-bodied

Hammer, as the trading at the end of the day managed to surpass the opening

value, but in my experience the market makes very little differentiation

between red and green real bodies on this pattern.

It’s the

length of the lower shadow that is probably more important, followed by what

happens in the days after the Hammer is posted.

Hammer summary

A Hammer

is a single candle reversal pattern that’s found in a market that has been

falling, with a small real body at the top end of the candle’s range, which

leaves a long lower shadow.

The

Hammer is one of my favourite reversal patterns, whatever the time frame of the

chart being viewed. I have found them to be particularly effective on liquid

exchange-traded futures contracts like T-Notes, Bunds, the DAX Index and Gold,

especially when viewing short-term time frames like 10-minute or 30-minute

charts.

Later on

when I expand upon different time frames we will see plenty more examples of

Hammers. It really is an amazingly effective and powerful reversal pattern when

used in the correct way!

Uses of Candlestick Charts : Chapter 3. Single Reversal Patterns : Tag: Candlestick Trading, Forex : Single candlestick patterns, Types of candlesticks, Powerful candlestick patterns, Types of candlesticks, Candlestick chart analysis, Bearish candlestick patterns - Single Reversal Patterns