Moving Average Cross Strategy

long trades, Short trades, Moving Average, Best entry techniques, Potential Trade Area

Course: [ Best Trading Entry Techniques : Trade Entry Techniques ]

the ‘moving average cross’ entry technique, let’s reiterate a few assumptions first. These assumptions apply not only to this chapter, but also to all the techniques in the following chapters

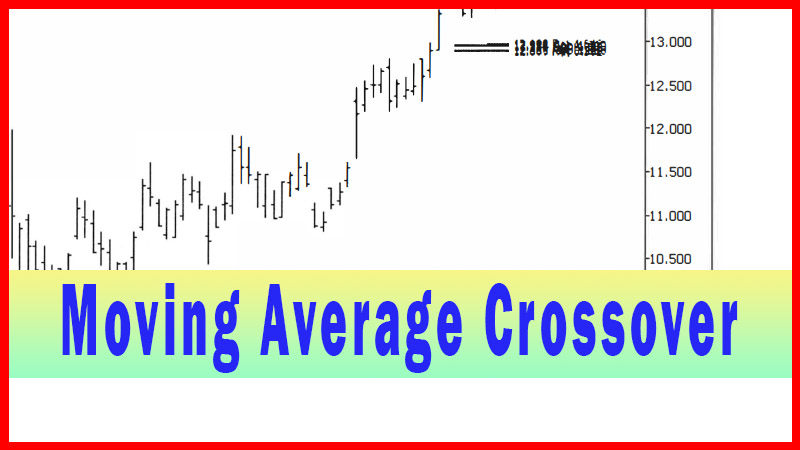

Moving Average Cross

Before we proceed on to the details of the ‘moving average

cross’ entry technique, let’s reiterate a few assumptions first.

These assumptions apply not only to this chapter, but also to all the

techniques in the following chapters.

First off, it’s assumed one wouldn’t even be

looking at an entry technique unless criterion one, the potential trade area,

has already been addressed. Next, once an entry technique is decided on and

trade size determined, it’s assumed one will have addressed criterion four,

trade management, before the entry is

actually taken.

This should be obvious, since if you initiate

the trade and then try to figure out how you will manage it, you will be trying

to figure out critical details ‘in the heat of battle’. That is something you want to avoid

like the plague. I want to make all critical decisions in the cool, calm of the

off-market hours. I want to have one sole purpose when the market is ‘live’,

and that’s to be an execution robot.

If I’ve laid out all the possible scenarios

that can occur, and pre-decided on what my action(s) will be when they occur, I

can simply be an ‘execution robot’ when the pressure is on. I can’t

over-emphasize how important I feel it is to not make decisions on the fly.

This doesn’t mean that you don’t take action on the fly, but means that you

don’t have to think out different courses of action, decide on the possible

outcomes of these courses of action, and weigh up the pros and cons on the fly.

That’s a recipe for disaster, in my opinion. I make all my decisions before the

market opens.

Now given all these assumptions, and the

context of the entry technique within the plan, let’s move on to the techniques

themselves. I will present quite a few techniques in the chapters that follow,

and each has its own ‘personality’. I use different techniques for different

situations. A lot of the basis for my decisions on which technique to use in a

given situation is experience, and that’s something I can’t give you. I will

give you hints and tips on my thinking process as often as I can, but to some

extent you will have to experiment on your own and test the ideas with your own

style, in order to make your own decisions on which technique you might use in

a given situation.

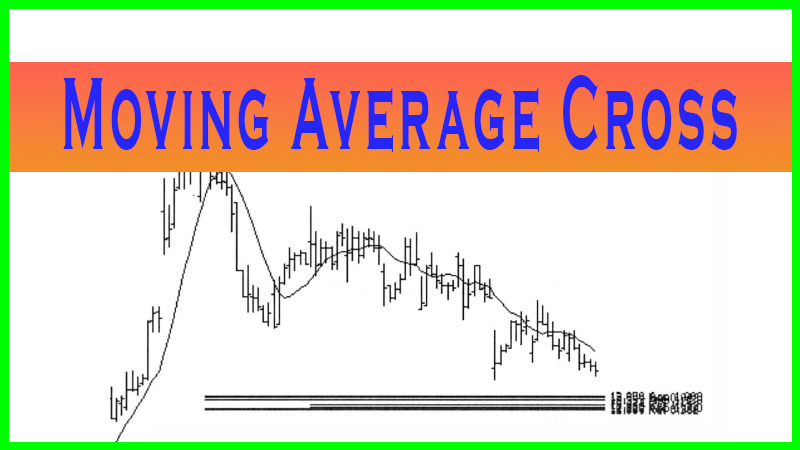

The moving average cross technique is an

extremely simple technique to set up and use. Entry is simply triggered when

the moving average is crossed, as the name implies. But does that mean as soon

as the price crosses the average? Or when it closes for the first time above (for long trades) or below (for

short trades) the average? And what moving average? Simple or exponential

moving average? What period for the moving average?

The moving average cross entry may work for

you, but only if you tailor it to your style and needs.

As soon as you think about tailoring something

to fit your needs, you see that there would, then, be no single way to

configure it so that it would work well for everyone, in varied situations.

This is perhaps the single-most important thing you should take from this book.

A technique is only as good as how well you are able to utilize it to suit your

own personal needs.

By this, I don’t

mean optimizing. I don’t mean to tweak it until it maximizes the results in back

testing. I mean pick techniques to meet a specific need you have, techniques

that are suited to the unfilled part of your plan. Let’s get more specific,

looking at the moving average cross technique.

This technique, as I mentioned, is extremely

simple and easy. Right off, that tells you that you shouldn’t expect too much

from it. It would be a technique I would use, then, when I don’t need a lot of

confirmation. That’s the first screening tool I use when trying to decide on

which entry technique I might use. How much confirmation do I want? Each entry

technique could be roughly assigned to a level of confirmation that it provides.

It only makes common sense, then, that the

less confirmation a technique provides, the more signals you will get, and that

more of those signals will be false. If you want a lot of confirmation, you’ll

get a lot less signals, but usually a lot less false start. Another thing I

frequently see is that the less confirmation the signal provides, the closer

your stop can usually be.

This puts you into a decision-making process

where you see that you can frequently stop out with a smaller loss on the lesser

confirmation techniques, but you will take a larger number of those losses. On

the other hand, as you go up the spectrum towards larger and larger degrees of

confirmation, the losses will be larger and larger, but less and less frequent.

In my experience it’s just about a wash, with all the techniques being roughly

the same over the long run.

So why have multiple techniques? My next

screening tool is to screen for a technique that is better suited to the way

that particular issue is trading at that time. When I say that I think that the

net variance between each technique is a wash over time, I say that given the

assumption that the techniques are applied only when the conditions are

suitable for that particular technique. I will do my best to state how I best

like to use each technique, and give examples, as we go along.

Looking at the moving average cross technique,

we know it is simple and has very little confirmation. That begs the question,

‘When would I want just a small amount of confirmation?’ For me, step one is to

choose my ‘potential trade area’, as discussed earlier. But not

all setups are equal. You can make a judgment as to how confident you feel

about that setup.

Let’s make one thing clear, though, about your

judgment call on the setup.

Be wary of relating your emotional feelings

about the trade to your level of confidence. Frequently the best trades can be

the scariest. If you judge the confidence you have in a trade based on this

emotional fear level, your judgment could frequently be exactly opposite of

what it should be.

I’m talking about a technical judgment based

on comparing the setup to a group of similar setups from your experience base.

You might be saying ‘Given this type of setup, I rate this one a seven out of

ten, compared with the large group of these I have seen and traded in the

past’, or something to that effect. Perhaps you decide you will only trade ones

that rate from seven to ten, and that a seven requires a maximum confirmation

technique and then a gradient applies, and the setups that rate a ten match up

with the techniques that have the least amount of confirmation.

But why does it that way? Why not just go with

the maximum confirmation in every case? Remember, the more confirmation you

desire, the smaller the number of trade signals you will get, and the greater

the distance your entry point will likely be from a logical stop loss point. By

not using the ‘least restrictive’ technique that fits the scenario,

you may miss trades that perhaps you don’t want to miss, and pay more for that

entry than you otherwise would have to.

I, personally, try to use the least

confirmation technique I am comfortable with for that given trade. I feel this

is one of my better ‘secrets’ (well, it’s not a secret now!), and something I

can’t recall ever having heard anyone talk about before.

I also evaluate the potential trade area in

terms of what type of trade it is, to determine how much confirmation I want.

Although I have no hard and fast rules that I can quantify for you, I do apply

a fairly uniform standard to all my potential trades. Some trades are lower

probability than others, just by their nature.

This doesn’t mean that these trades may yield

less money in the long run (they may pay out more per trade), just that they

work out less frequently. For trades like that I prefer a larger degree of

confirmation. There is a gradient of trades and a gradient of triggers, and I

try to match them up as best as I can.

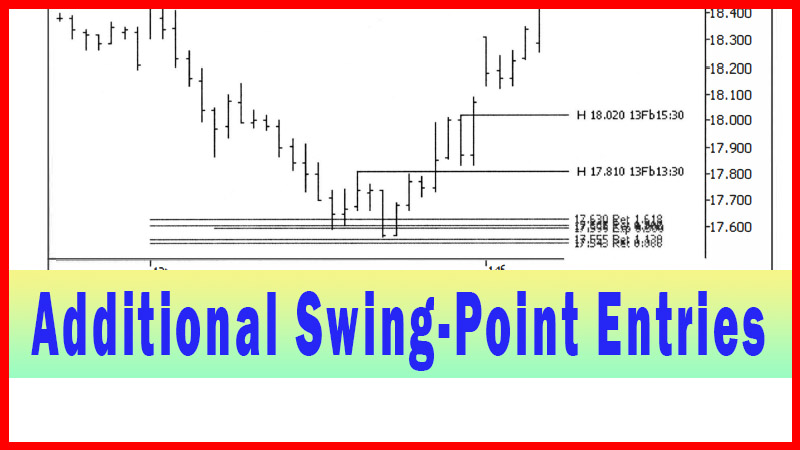

Let’s assume we have a potential trade area we

like, and if we get a trigger in this area, we want to take a trade. Let’s also

assume that we have decided that the trade is a fairly high probability trade,

and that the setup is looking really good so far. We are willing to initiate a

trade with just a small amount of confirmation. First, let’s look at an example

of a potential trade area, based on a Fibonacci grouping (for more information

on constructing and trading Fibonacci groupings). See figure 2.1.

A simple choice for a moving average cross

trigger would be a close above a 10-period simple moving average. This is a

middle of the road average for short-term trading, and the requirement of just

one close above the average is also middle of the road. This is a good starting

point to look at.

Let’s first look at the same issue as above,

but with the 10-period simple moving average on the chart. Before we do this,

though, let’s give this a little thought. Do we want to look at the issue on

the same timeframe? The answer is no, we want to go down one timeframe.

Remember, what I like to do is use three

timeframes, with the ‘middle’ timeframe being the ‘traded’ timeframe.

The higher timeframe is for context and the lower timeframe is for entry. I

usually use a timeframe ‘jump’ of approximately three to five times, but when going down

from a daily, I go a little more of a jump, in order to use a very common bar.

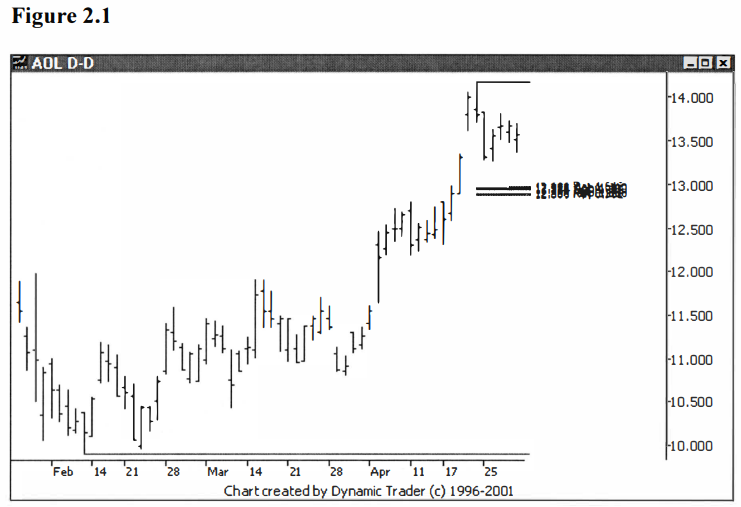

Hence, with figure 2.1 being a daily chart,

I’ll choose to use a 60-minute for entry. So, we’ll look at the issue, now with

a 10-period simple moving average, on a 60-minute chart. We’ll also move a

little bit ahead in time, as we approach the potential trading area. See

figure 2.2.

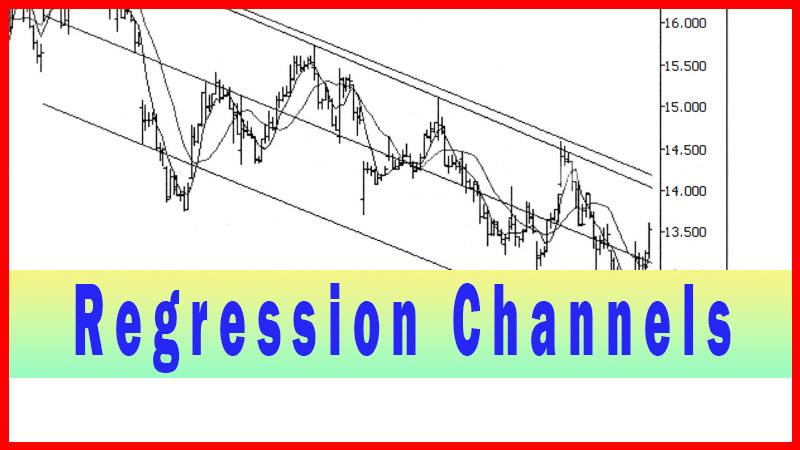

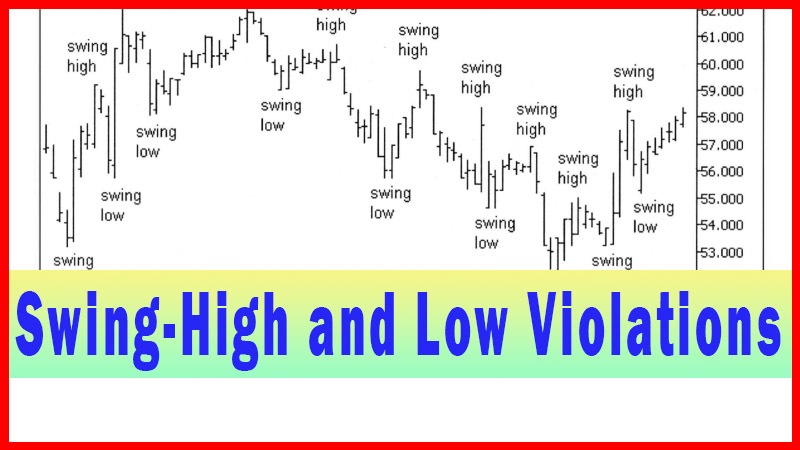

The first thing I notice is how ‘choppy’ AOL is with

respect to its 10-period moving average. My first inclination would be to

consider another entry technique here, one that perhaps is better suited to such

‘chop’. I would be thinking about a trendline violation technique or a

regression channel violation technique, or perhaps even a swing-high or low

technique.

I will cover all these in detail in later

chapters, and I will use this example again for comparative purposes. So why

even continue here with the moving average cross technique? I already stated I

felt very confident with the setup and so I preferred to have a lower

confirmation entry technique.

Remember, I like to use the least confirmation

technique that I feel is warranted, so as to maximize my number of potential

trades that trigger. Despite the ‘chop’, I still want to see how this one look

as it gets closer to the potential trade area. Let’s advance ahead in time as

AOL approaches the area, we might consider trading. See figure 2.3.

The first thing I notice here as time has

moved on a bit, is that at least AOL is behaving in a manner where I would

still consider using the moving average cross technique. I am looking for a

somewhat smooth decent into the area, mostly trending down and staying below

the moving average.

I don’t want AOL to be going above and below

the average multiple times. This is obvious, since each close above would be a

signal, and most would prove to be false signals. Keep in mind here what my

objective is. I think this grouping (or more precisely, two very tight

groupings) will reverse AOL and the larger daily timeframe trend will reassert

itself.

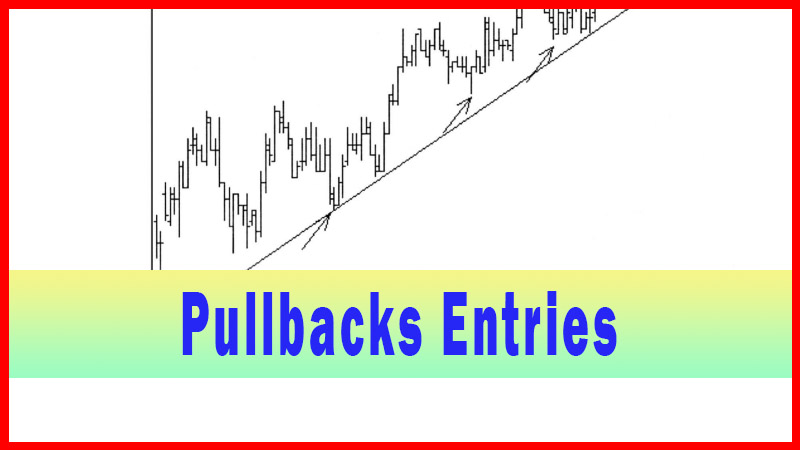

Some traders would simply ‘fade’ the trade and

take it as it enters the zone. This is a valid entry technique. It is on the

scale on the end that says ‘no confirmation’. You could move it on the scale a

tiny bit, to ‘a tiny bit’ of confirmation, by simply hesitating for a little

while and watching to see if the issue slows down or appears to stop, as

opposed to just plowing right through the area.

For me, I don’t like either of these two

techniques, although I do use them under certain circumstances. If I’m very

confident in the trade’s potential, I want just a bit more than the ‘fade’,

or the ‘fade with a pause’. Hence, I might choose the moving

average cross technique. This is why I am hanging with this AOL example up to

this point. Let’s watch as AOL enters the potential trading area. See figure

2.4.

What a difference a few bars can make. The

last bar is a very significant plunge into the top of the groupings, and is a

little disconcerting. I have noticed, though, that this is a fairly common

occurrence when trading Fibonacci groupings, and if AOL ‘straightens out’ and doesn’t

simply continue to plunge right through the zone, I’m still willing to take a

trigger if it comes off the grouping. Let’s continue forward a few more bars

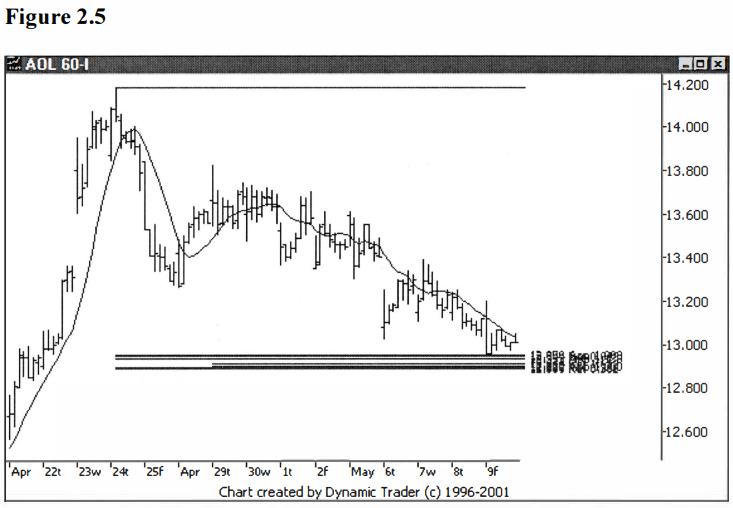

and reevaluate. See figure 2.5.

Now we are right at the critical choice point.

AOL has bounced right off the top of the first grouping and hasn’t closed above

the moving average for eighteen bars. It came off the grouping and went up a

bit, rolled down a bit, and is now moving up a little.

This might just be some congestion, or that

may have been it, a ‘test’ of the bottom and up it goes. I would prefer to get deeper

into the groupings, but we have ‘officially’ hit them, so a cross and close above the moving average now

would be considered a trigger that I would take. Let’s see what happens. See

figure 2.6.

Okay, I couldn’t ask for more on this one. AOL

gapped down on the next bar (which is also the open of a new trading day), went

right down to the top of the groupings again, and then rocketed up, closing

well above the moving average. In fact, it hit the low from the previous day to

the exact penny, and then buyers came in and it went up strong with an

expansion bar and a strong close.

At this point I would be triggered into the

trade. As an aside, I would be using the area of the tight groupings to choose my

stop placement, and I, personally, would be placing a stop just below the lower

end of the groupings. This is one of the main reasons why I like the grouping

technique so much, because it gives me some real nice choices for stop losses.

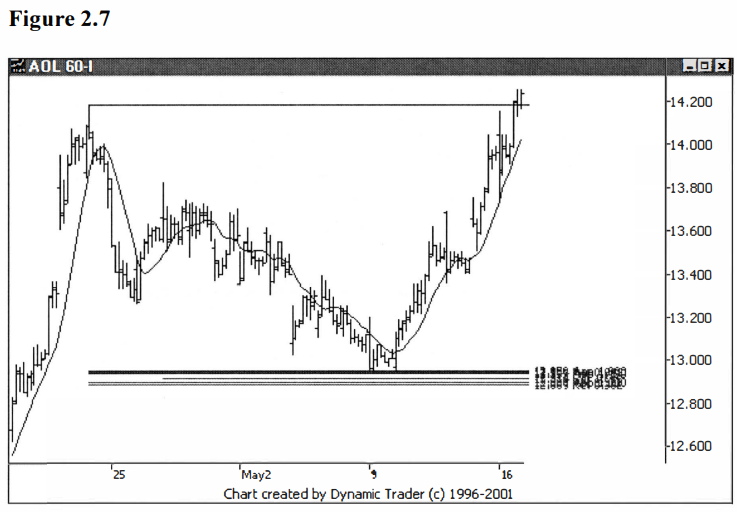

Let’s finish up this example with a look at

how AOL reacted to the grouping as more time passed. First let’s look at the ‘shorter-term’ trade on

60-minute chart. See figure 2.7.

This trade really came off that zone, and the

moving average cross technique did, in fact, work extremely well in triggering

the trade. But remember, the 60-minute chart was only used as the trigger

chart. The trade was on the daily. Don’t change your trade parameters and stay

with the trigger timeframe once you are in the trade. If you are trading the

daily, trade the daily. So, let’s look at how AOL responded on the daily. See

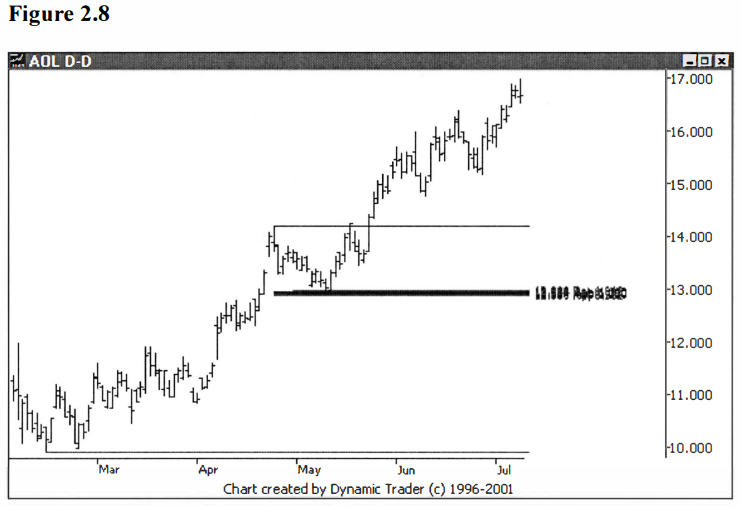

figure 2.8.

As can be clearly seen, this trade had quite a

way to go on the daily timeframe. If one would have stayed on the 60-minute

timeframe to follow the trade as it progressed, it is very likely that the

perspective would have induced the trader to take a quick profit, and miss most

of what was to come. It’s important not to forget the role of each of the

timeframes within the context of the trade, as well as the context of the entry

technique.

Let’s do one more example, this time with a

longer moving average, a 20- period. What effect, in general, will this have,

as compared to, say, the 10- period we just used? The 20-period will usually

take more movement on the part of the issue to overcome it.

This means you will likely get fewer false

signals. And you will likely be farther away from a logical, technical stop

loss point. You will have more confirmation, but you pay for it. I would

consider using the 20-period when I don’t have the amount of confidence in the

potential trade area as I have when I consider the 10-period.

I understand this may all sounds pretty

abstract or nebulous, but that’s not the intention. It’s just that I don’t have

any hard and fast rules for this. I make decisions based on experience. My

advice would be to look at examples of trade areas that you trade, based on

your style, and then look at the various entry techniques I have presented. See

which ones work best with each different type of trade, and try to see which

ones work best for you, and under what circumstances. Try to match the

technique to the trade.

In essence, that is what I have done. There is

no perfect answer, it's just a matter of finding what works best for your style

and your types of trades. It takes a lot of off-market hours chart work to

figure that out, but that’s trading.

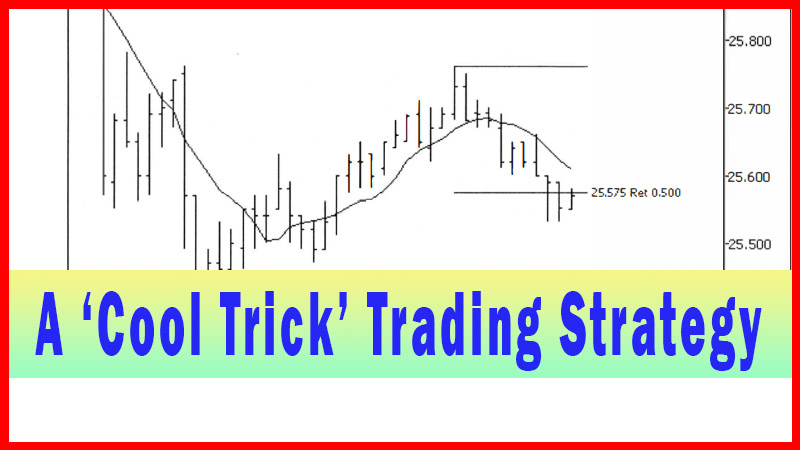

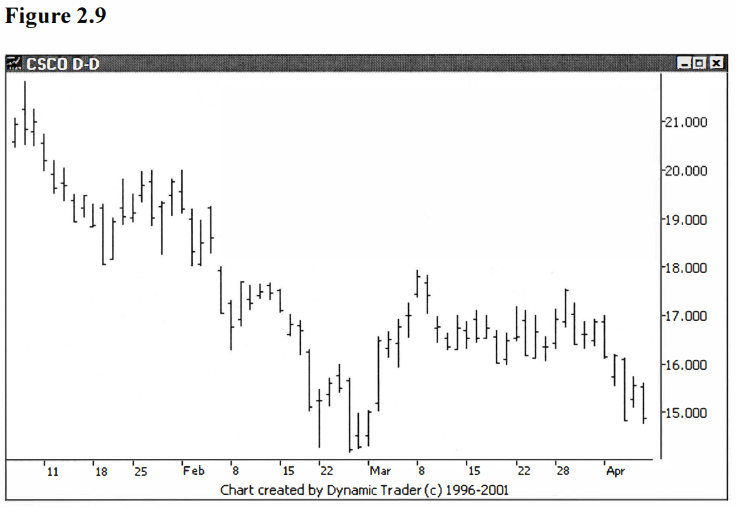

Let’s look at CSCO. I noticed CSCO had been in

a fairly strong downtrend on a daily chart. I had also noticed that it had had

a fairly good-sized correction to the downtrend in the end of February and

beginning of March, and then it resumed its downtrend. I am looking for a

chance to get on board the downtrend. See figure 2.9.

I also realize that, perhaps, we would be

looking at a short trade right in an area of potential support. I, myself,

would want a little bit more confirmation on a trade like this, and I would

only consider it if the groupings looked pretty good and the larger scale

picture warranted it. Of course, the techniques presented are not limited to

use with Fibonacci groupings, I only use the technique here because it is one

of my main ways of trading. Let’s look at a potential trade area for this

chart. See figure 2.10.

The next step would be to dial down to a

smaller timeframe; again, in this case we’ll go to a 60-minute chart. I’ll also

add in the 20-period simple moving average. See figure 2.11.

CSCO is approaching the potential trade area

and is trending up quite smoothly. It is also getting stretched quite a bit

away from the moving average. This can be good, in the sense that issues tend

to be ‘mean- reverting’, that is, they frequently return to

the average.

Having the issue stretched right at the point

when it encounters the groupings can stack the odds more in the favor of the

trader. On the other hand, the entry can be quite far down in this case, with

the stop loss, perhaps set just above the groupings, very far away. That can be

the price for wanting that much confirmation.

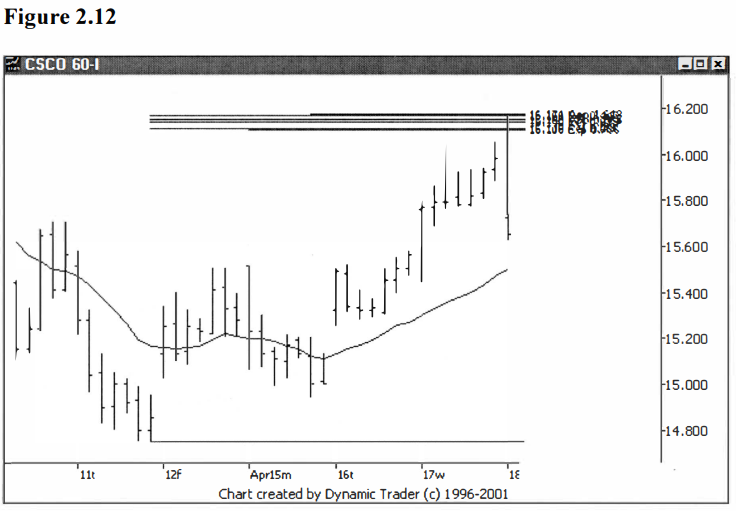

Let’s move ahead one bar and see how CSCO is

acting. See figure 2.12.

Wow! CSCO gapped down, ran hard straight up to

the groupings, and reversed on a dime and closed the bar below the opening, and

right near the bottom of the bar. It’s plain to see that it didn’t like that

area one bit. It seems that it’s now trading quite far away from the area, and

it still hasn’t closed below the moving average.

If you want more confirmation, this is

something you will have to accept. If you had chosen a faster moving average

you’d likely be in the trade at this point. On the other hand, the amount CSCO

has dropped in fairly small in the context of the daily chart, and that is the

traded timeframe for this trade. Let’s look at CSCO after another bar has

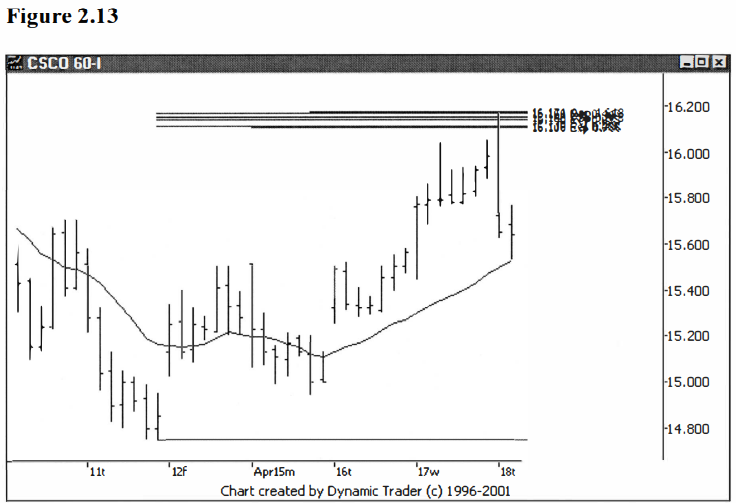

unfolded. See figure 2.13.

CSCO is still coming off the grouping nicely,

and has dropped just about to the moving average. A close below the moving

average is the trigger. Let’s advance one more bar. See figure 2.14.

That’s it; the trade would now be triggered at

this point. The trigger bar is quite interesting, and worthy of some

discussion. The bar opened pretty close to the previous bar’s close, and it

closed about midway on the bar, with the close below the open. But it was quite

a large expansion bar, with a large lower tail.

If one was strict with the rules, the bar met

the criterion for an entry. This brings up the question of ‘second guessing’.

This bar had a lot of lower-level action, and then it reversed and went up

quite a bit before it closed. Given how far CSCO had already dropped, I might

be thinking it was time for some corrective action to the decline.

If I followed this line of reasoning, I might

decide to abort the trade entry, or sit tight and see how it plays out. The

danger is, the trade may play out exactly as anticipated, and the trade may be

missed. I have found that, although I sometimes ‘guess’ correctly and save

myself a stop out, I frequently watch the trades I skip do exactly what I

originally expected they do.

My point is, for me, I rarely second guess

them. Unless I see something really blatant (and that’s a subjective, experience-based

call), I take the trade if it meets my pre-defined trigger conditions. Let’s

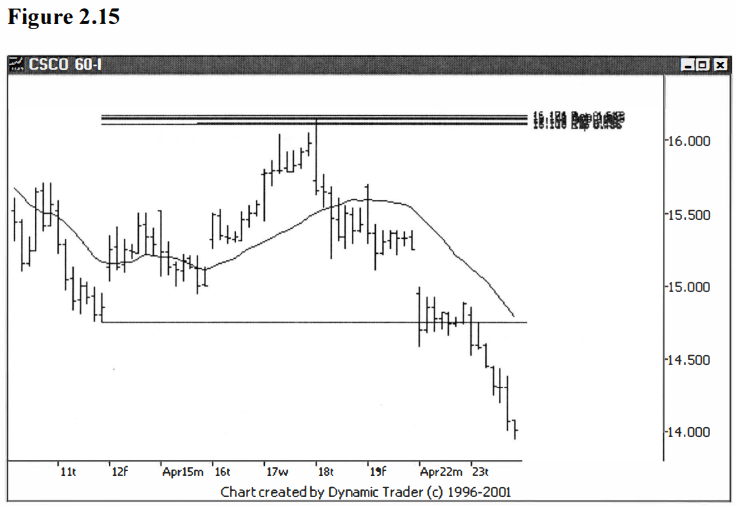

look at how CSCO played out shorter term, on the 60-minute chart. See figure

2.15.

As it turns out, the entry signal would have

worked quite well. There was one bar where it looked like CSCO may have been

reversing, but that bar barely exceeded the expansion bar’s high, only going

one cent higher. Any technical stop you likely would have been using at this

point wouldn’t have even been approached. But remember, the traded timeframe is

the daily. This little blip is hardly noticeable on the traded timeframe. See

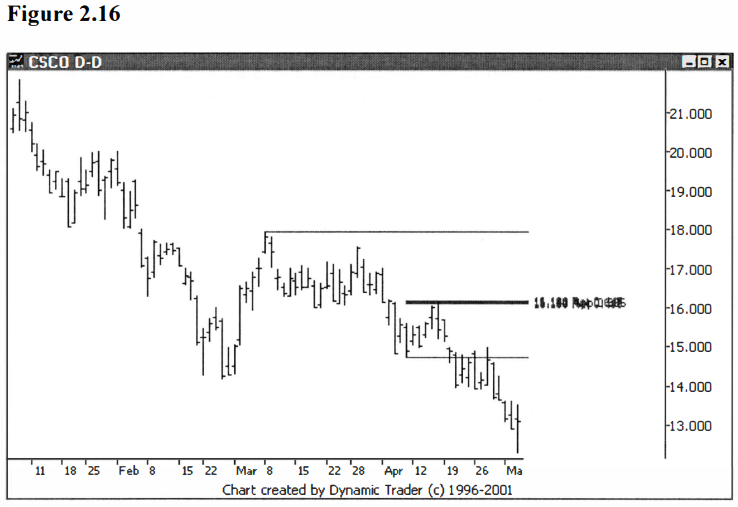

figure 2.16.

The trade offered quite a bit of a chance for

taking profits and letting some part of the trade ride. When I trade a trend, I

usually scale out and take most of my profits by the time the previous

significant swing-low is exceeded and reaches the area of the 1.272 external

retracement from that swing-low. (The swing-low I am looking at was on February

27, and the swing-high was on March 8).

Although many trades exceed this number, few

go beyond the 1.618 external retracement. Hence, I always put these on my

chart, to help guide my trade management. I mostly use trailing stops for the

majority of my profit taking.

But trailing stops can vary, and how tight you

trail them can depend on where you see potential reversal areas, and areas of

potential support and resistance, coming in. In a nice, reasonably smooth

trend, I’m always watching the area between the 1.272 and 1.618 external

retracement area very closely, and usually have most of my trade off by the

time that area is reached.

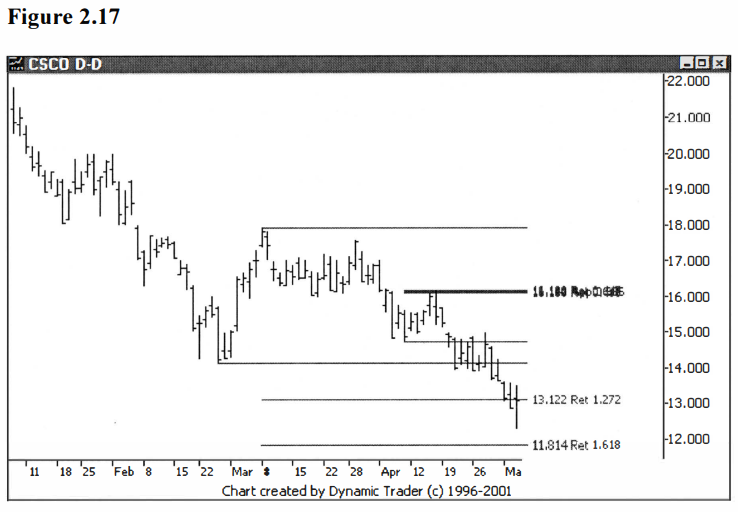

Let’s look at the same daily chart as in

figure 2.16, but with the 1.272 and 1.618 external retracements added on to the

chart. See figure 2.17.

It can clearly be seen that CSCO is right into

that zone between the retracements. In a case like this I would likely have

scaled out of most of the position, using a variety of techniques, with heavy

focus on trailing stops. I will refrain from any further discussion on trade

management here, so as to stay on topic for this book, but I am pointing this

out here for a reason.

I chose this example from the beginning

because, although it did work out quite well, it didn’t work out as well as it

may have. And it is about to throw a curve ball at any trader who is still with

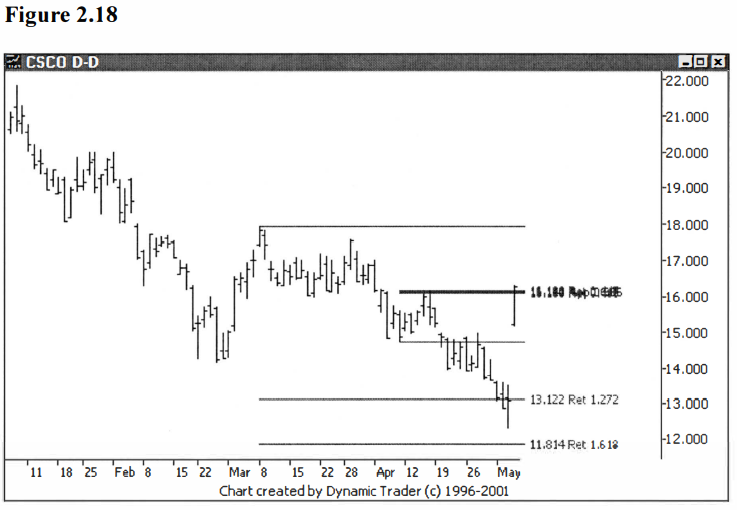

the trade. Let’s move forward one more bar and see what I am talking about. I

will remove the anchor line from the swing-low on February 27, to help with clarity.

See figure 2.18.

BAMM. A huge reversal, with a massive gap up opening. Low

to high, this is over a 32% move in one bar! The spinning top bar in the

1.272/1 .618 external retracement area was a big-time red flag. But even if you

decided to hold some of the trade at that point, all would not be lost.

The original entry on the trade was at the

close of the first 60-minute bar below the 20-period moving average, and that

was at 15.46. Assuming you would sell on the gap up opening, or thereabouts,

the opening price was 15.23. (Keep in mind that the prices I mention are the

prices when you might be looking to get in and out of the trade. I’m not

suggesting that anyone could actually have gotten these exact fill prices. I

use these prices only as examples, to get a general idea of what’s going on

here.) Given this, the remaining part of the trade would be a scratch.

All in all, I’d consider that a pretty decent

trade. But it still serves as a good example of one of the many things that can

happen in a trade, and how important good trade management can be.

In this chapter we’ve looked at two different

moving average cross entries. One was entry when the first bar closed above a 10-period simple moving average (this was a long trade),

and the other was when the first bar closed below a 20-period

simple moving average (this was a short trade). There are many other

variations, and I encourage you to experiment and find which, if any, help your

trading.

I, myself, like to use a 5-period simple

moving average when the issue is trading smoothly into the zone and I have a

high degree of confidence in the trade. As you may suspect, this is a very fast

setting and is extremely prone to whipsaws. I use it when I’m only one step

away from just wanting to fade into the trade if it hits the zone and stalls.

When I use this technique and want just a bit

more confirmation, I use the 10-period simple moving average. I rarely use any

other variation than the 5 or 10-period simple moving averages. I find that I

prefer other techniques to using a longer period average than the ten. You may

find, though, that your preferences may be different.

Keep in mind that you can also experiment with

exponential moving average, weighted moving averages, and other newer

generation moving averages. To simplify this discussion, the following applies

to long trades; simply reverse for short entries.

You can look at triggers other than the first

bar close above the moving average. You can look at when the issue first trades

above the average, that is, when it breaks the average with just one trade. You

can also look at taking out the high of the first bar that closes above the

average, or taking out the high of the first bar that trades above the average.

The point is, there are a lot of possibilities here,

and it’s a great idea to experiment, on paper, with as many possibilities as

you can think up. Find what works the best for you. Examine and experiment with

not only all the techniques I present in this book, but also with variations on

all the techniques. Try to find the techniques and the variations that suit

yours needs as best as possible.

Best Trading Entry Techniques : Trade Entry Techniques : Tag: Trade Entry Techniques, Forex : long trades, Short trades, Moving Average, Best entry techniques, Potential Trade Area - Moving Average Cross Strategy